In light of the recent Martin Luther King Jr. Day holiday this Monday, we should take the time to reflect on Martin Luther King Jr., his legacy and its relevance to the current state of affairs at the University of Minnesota.

The Black Liberation Movement and Civil Rights Movement won many victories in the struggle for racial equality in the U.S. The Civil Rights Acts of 1964 and 1968, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and the overturning of Plessy v. Ferguson were the legal manifestations of the success of this movement, and all occurred before King was shot. Before he was murdered, King recognized that his dream was not yet realized; equality in the eyes of the law was only the beginning. At the end of his life, King identified that the war on black Americans was intimately connected to the Vietnam War and to long-term structural economic inequality. He realized that the struggle for racial justice in the U.S. was still far from over. We should remember King and take up where he was forced to leave off.

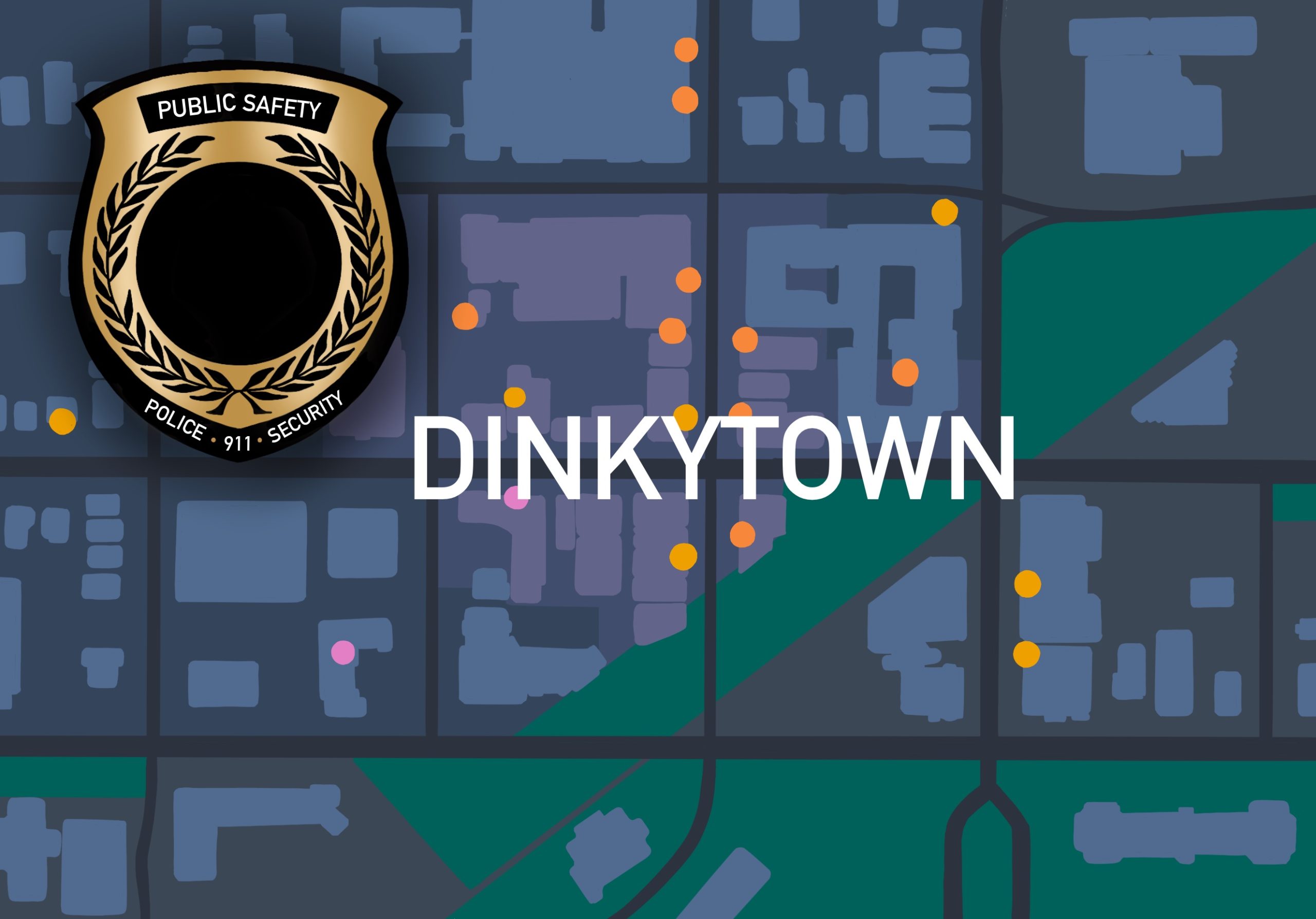

At the University, we are reminded of continued racial tensions almost daily by the crime alerts consistently identifying black young men as criminal predators. Some students seek to end crime on campus by demanding increased police presence, but this does not address the root reasons for crime and will only lead to increased racial profiling and vigilante terrorism, as was seen against Trayvon Martin and Terrance Franklin.

The criminalization of young black men is not the only consistent racial injustice on campus; there are also structural barriers to access. This is not a new problem, though. In January 1969, less than a year after King’s murder, students occupied Morrill Hall, home to University central administration, with a list of demands aimed to fight racism on campus and increase access for underrepresented populations. Students demanded full scholarships for black high school students, guidance and counseling for black students and more black faculty, among other things. With their actions, students forced the administration to make concessions, one of which was the establishment of the African American and African Studies Department.

Although this marked a victory for black people on campus, there are still battles to be waged. For example, black and Latino/a people continue to be largely underrepresented in our student body. The University has an undergraduate student body that is only 4 percent black, 2.4 percent Hispanic and an overwhelming 66.8 percent white. Standing in stark contrast, the city of Minneapolis is 18.6 percent black, 10.5 percent Latino/a or Hispanic and 63.8 percent white. Furthermore, while the poverty rate in Minneapolis has climbed to a remarkable 22.5 percent of residents, the University’s tuition has doubled in the past decade, economically squeezing Minnesota’s poorest students out of our state’s flagship university and freezing economic mobility.

To address this, the University needs to make immediate steps to bridge the gap between its student demographics and the city demographics. An urban university should reflect its urban population. Tuition needs to drop to a level that is affordable to all Minnesotans, not just its wealthiest families. Students should recognize that King’s struggle is far from over and that the only way to achieve his dream is by becoming active in the fight against injustices on campus. This means opposing racial profiling, looking to the root causes of racial and economic inequality and getting involved in the next round of student movement organizing.

A good place to continue the fight for King’s dream is in student activist organizations like Students for a Democratic Society, the La Raza Student Cultural Center and the Black Student Union.