Though new University of Minnesota research could break ground on treatment for Parkinson’s disease, Jackie Christensen, who was diagnosed with the illness 18 years ago, said she has a hard time imagining a fix for her daily struggles.

“There’s not a short answer,” said Christensen, who is also the state of Minnesota’s director for the Parkinson’s Action Network. “I think it’s hard to find a cure because we don’t know what causes it in most cases.”

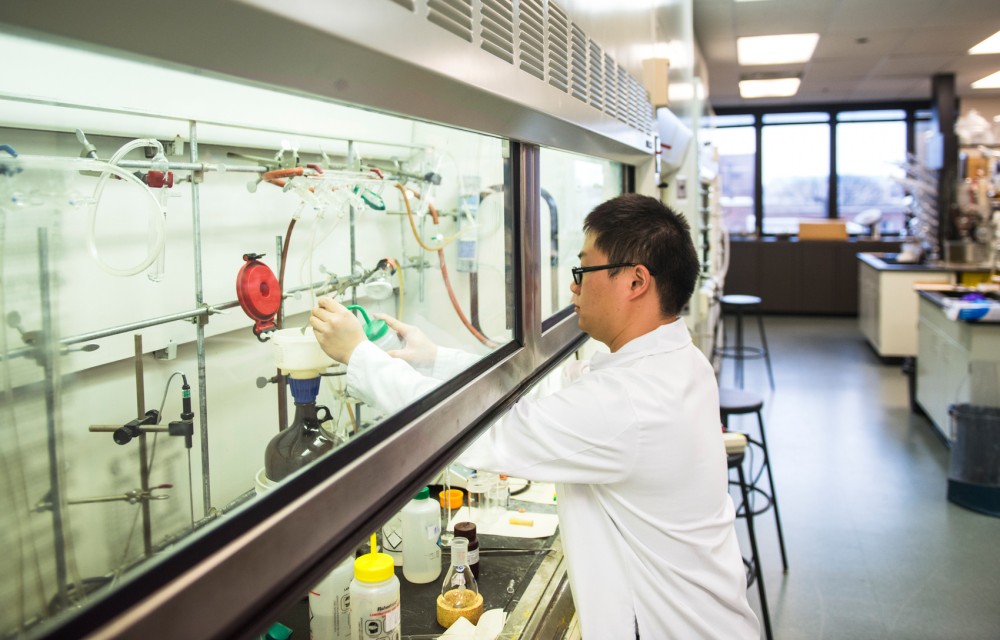

But Liqiang Chen, assistant professor at the University’s Center for Drug Design, said he and his team of chemists have discovered powerful inhibitors that may be able to stop one of the disease’s leading contributors. The results of their work were published in the September Journal of Medicinal Chemistry.

Each year, U.S. doctors diagnose between 50,000 and 60,000 people with Parkinson’s — in addition to the country’s existing 1 million cases.

Chen said because the disease stems from the nervous system, it’s necessary for treatments to cross the barrier between the brain and the circulatory system — but he said only about 2 percent of all FDA-approved drugs do so.

In order to be effective, Chen said, the pill needs to cross the blood-brain barrier.

A drug currently on the market named Levodopa increases the brain’s dopamine levels, but it only treats some of Parkinson’s symptoms, such as tremors, stiffness and slow movements.

Christensen, who has sporadic Parkinson’s, said while most other patients have tremors, she doesn’t suffer from that particular symptom.

“I tend to move fairly slowly, which is often very annoying,” she said.

Chen said an overwhelming 90 percent of Parkinson’s cases are sporadic, while only about 10 percent are genetic. He said the illness’s common variety is more difficult to correctly treat.

But he said he hopes the potent and selective compounds his team discovered could offer a solution for those patients.

His team used a three-step process of linking, merging and growing compounds to examine their drug-like properties. The researchers found the successful compounds — or Sirtuin 2 inhibitors — by piecing together combinations of hundreds of those compounds until the correct ones fit together, according to the study.

Daniel Wilson, a research fellow at the Center for Drug Design who aided the proposal for Chen’s compound research, said the discovery will not necessarily spawn a cure, but rather a treatment for the disease.

Chen recently applied for NIH funding to support the drug’s next steps, which include animal, and then human, testing.

“We need to make sure it behaves well in animals,” he said. “I hope it is a beginning of big things.”

Patti Manner

Nov 20, 2024 at 10:34 am

I’m a caregiver for my HWP. I wanted to inform PWP that there’s hope, the binehealthcenter. com has been of great help. the PD-5 treatment programme they offer has completely help with reversing my husband Parkinson’s symptoms.