Minneapolis, UMN respond to homelessness as harsh weather begins

After months of encampment clearings in Minneapolis, many unhoused residents now face winter without a home.

Published December 15, 2022

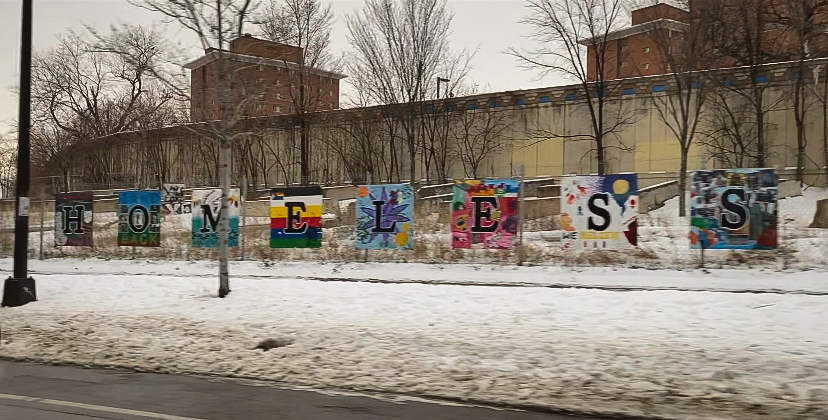

Wet blankets and abandoned clothes scattered the streets in a place that residents used to call home. Tents rattled against the newly placed fence with broken chairs and tables laying in the snow. This homeless encampment was recently evicted by the Minneapolis Police Department (MPD).

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, a series of federal and state eviction moratoriums prevented renters from being evicted from their homes. Minnesota enacted an “off ramp” timeline in June 2021 to gradually phase out eviction protections. All restrictions were lifted on June 1.

Roughly 300 people experiencing homelessness were unsheltered on a single day in 2021, a nearly 84% decrease from the year before, according to the state’s Homeless Management Information System (HMIS).

In 2022, the state’s unsheltered population increased to nearly 1,800.

“At the end of the day, the problem continues to be not enough affordable, sustainable, accessible housing,” said Steve Horsfield, executive director of Simpson Housing Services, a nonprofit working to find sustainable housing for people across the Twin Cities.

Sanctuary Supply Depot distributes supplies to encampments

At 2:05 p.m. on a Friday afternoon, 52-year-old recovering drug addict Jack Nobles is working to salvage recovered supplies from people who had been evicted from their homes on the morning of Dec. 2. He does not have a high school diploma, but he has blankets and duffel bags filled with clothes to help those who may have taken “one wrong turn.”

“This whole notion that these people deserve what they got, that they did something wrong –– they didn’t do anything wrong,” Nobles said. “They’re just victims.”

Behind the shelves of the Minneapolis Seward neighborhood’s Boneshaker Books sits the Sanctuary Supply Depot, a nonprofit volunteer organization that collects supplies for homeless people to bring to encampments.

The Sanctuary Supply Depot was founded in response to a fire at the Francis Drake Hotel that displaced 250 Minneapolis residents of the low-income hotel in 2019. The Depot takes donations from volunteers to homeless encampments, shelters and other nonprofit organizations around the city.

Nobles said the Depot is at their breaking point with the increasing number of homeless people who are in need of help and supplies.

“We’re literally six people in the back of an anarchist bookstore, and it’s just non-stop,” Nobles said. “Everyday there’s more people who are homeless and there’s more people in need.”

In Minneapolis, financial barriers keep housing inaccessible for those experiencing homelessness, Nobles said. These barriers include paying the $25 to $40 down payment the majority of complexes ask for before leasing an apartment and accessing different technology sources that are not accessible to many people experiencing homelessness since most people find apartment listings on the internet.

Nobles continues to encourage people to support those who are homeless by offering out a helping hand through volunteering when they can and donating supplies.

“One of the most important things about the unhoused is they feel forgotten and invisible,” Nobles said. “Just talk to them. Show them some humanity because we’ve done everything to these people but show them compassion.”

Finding a home

A defeated man walks into the Dinkytown Starbucks with bags under his bloodshot eyes and cuts on his dry hands, carrying a duffel bag and sleeping bag with white tape wrapped around broken shoes. There are holes in his jacket after receiving the news that his home was destroyed by the MPD.

Although he was unhoused, James had a home in the Franklin Hiawatha Encampment, located behind the

Minneapolis American Indian Center, before it was evicted and closed off Dec 2. Now, after watching his home be demolished, James is one of many people looking for “anywhere that would take him.”

“I don’t really have anything in my life, but I had my home,” James said. “[The MPD] took my home away from me.”

James felt like he “didn’t matter” because of how he was treated by the MPD and was a burden to the city he had called home. Others said they understand this feeling.

After first experiencing homelessness when he was 8 years old, Andy grew up finding shelter on friends’ couches, in motels and on heating vents while hiding at school overnight. Despite being unhoused once again more than a decade later, Andy said he still finds himself lucky to have people who are willing to support him.

Both James and Andy chose to not give their full name due to safety concerns that come from a stigma surrounding people experiencing homelessness.

In the more than four years since Andy began working to distribute supplies with the Sanctuary Supply Depot Collective, he said many unhoused people are not homeless, as they make their own homes wherever they can.

“The encampments, especially those tents, that’s their home, and those people are their family,” Andy said. “To the outside, it looks horrible and people will deride them for it, but it’s where they live. It’s their home.”

On a typical day in an encampment, some residents begin waking up as early as 4 a.m. because they train themselves to be awake and out of doorways before anyone notices, Andy said. Each day’s schedule can often rely on when outreach organizations like the Supply Depot bring food or supplies.

By late morning, most residents have started their day. Some have eaten, others may have showered using water bottles and tarps for privacy. During the day, many encampments are largely empty as residents go to work, attempt to use social services or ask for money on street corners, Andy said.

Roughly once per week, police evict encampments during the day when fewer campers are there, Andy said. In some encampments, adults return from work and kids return from school around 4 p.m., if there is still a home to come back to.

“Anybody who is marginalized is going to feel that ‘everyone for themselves’ feeling, so it takes a lot for them to work through that and start working together,” Andy said. “It’s been worse in encampments lately because of how much they get destroyed … They don’t know if their tents are going to be there tomorrow, if they’re going to see these people tomorrow, or if they’re going to be in jail or even have their stuff tomorrow.”

As part of Minneapolis’ procedure for evicting encampments, the Homelessness Response Team –– which includes police –– offers unhoused residents resources such as different shelter options.

One of the city’s offered resources is Adult Shelter Connect (ASC), which works to provide shelter for anyone 18 years old or older in Hennepin County. The service is part of a collaborative made up of five agencies working to house residents locally.

Simpson Housing Service, a member of ASC, has offered shelter and other programs to people experiencing homelessness for 40 years. Despite the city offering it as an option to evicted residents, Simpson does not have the resources to support everyone in need of its resources, according to Horsfield.

“To whatever extent there’s any capacity for diverting somebody back to the housing situation they’re coming from or another option, we want to make sure those options are being explored before somebody comes into the shelter system because those beds are dear,” Horsfield said. “Very frequently, someone calls in seeking shelter and we don’t have it.”

People seeking short-term shelter for up to 10 days can call and reserve one of the roughly 600 beds in Simpson’s housing system, Horsfield said. Anyone in need of longer-term housing may need to be transferred into other shelter care.

As of Saturday, there are 39 overnight beds and one extended stay bed open for single adults in Hennepin County’s ASC system.

Simpson “respects the autonomy of the individual” to choose where they find shelter wherever they can, including outside or in encampments, Horsfield said. However, the health and safety concerns from living in an encampment during the winter is leading Simpson to put additional effort into getting as many people into housing as possible and ensuring there are available shelter beds for anyone in need.

“In particular, having to turn somebody away when it’s freezing outside, it hurts,” Horsfield said. “We all do this work because we’re deeply committed to caring for people and we believe housing is a human right. When the resources are insufficient for the need, it’s a painful thing to have to say no.”

Minneapolis’ eviction response

Apart from clearing the Franklin Hiawatha Encampment in December, MPD evicted several other encampments throughout October. Activists, including Andy, held a week-long protest outside Minneapolis City Hall.

Protestors pitched tents and raised signs telling city officials to stop encampment evictions before being broken up by officers. Communities United Against Police Brutality President Michelle Gross is working to assist people who were evicted from the encampments and said the protest aimed to bring attention to people experiencing homelessness because “the way the city of Minneapolis and police are addressing this issue is reprehensible.”

“Sometimes, you have to make it clear that it won’t be business-as-usual if [Minneapolis] keeps this up,” Gross said.

In an 8-5 vote, the Minneapolis City Council failed to pass Council Member Aisha Chughtai’s (Ward 10) proposal to pause the removal of homeless encampments on Oct. 20. The council passed another measure from Chughtai requiring the city to provide financial reports for encampment closures in the past five years.

“The City of Minneapolis responds with inhumane tactics and does not systematically advance the reduction of homelessness,” Chughtai said during her proposal. “We should be striving for every resident in this city to be housed. That’s not the reality of the world we live in. A policy and action plan on homeless encampments that centers humanity, dignity and safety is the least we can offer residents.”

Chughtai said Minneapolis’ current eviction protocol for encampments damages valuable belongings, traumatizes residents and contributes to the creation of new encampments as unhoused residents seek new shelter.

Although MPD officers can be seen during encampment evictions, police do not perform them and work to recognize the individual needs of encampment residents, according to MPD Public Information Officer Garrett Parten.

“MPD’s role in homeless encampment closures is supportive as part of a multi-departmental city response,” Parten wrote in a statement to the Minnesota Daily. “MPD’s role is to be present, to promote and ensure safety for all throughout the closure.”

Nearly 8,000 Minnesotans experienced homelessness in a single night in 2022, about 2,600 of which reside in Hennepin County, according to HMIS.

Minnesota’s total unhoused population has increased roughly 16% compared to 2021, according to HMIS.

Minneapolis has worked with the state and other partners to invest more than $200 million into improving its homelessness response system since March 2020, according to city spokesperson Sarah McKenzie. The investments aimed to improve living conditions of existing shelters, create accessible new shelters and increase social worker staffing.

Additionally, Minneapolis has roughly increased its production of affordable housing and offered 199 units per year since 2019.

Despite the city’s investments, Councilmember Robin Wonsley (Ward 2) said with the failed proposal, city leaders are telling unhoused residents “that you don’t matter, you don’t deserve respect, that we wish you stop existing, that you are a nuisance, that you are a problem, that you are not human.”

Wonsley voted to pause encampment removals in October.

Several council members who voted to reject the proposal cited concerns over whether the council had the authority to pause encampment removals under the city’s new government restructure, which relegated the City Council as a legislative entity and placed more administrative power in the mayor’s office.

However, Wonsley said the government’s restructure has been “politically weaponized” as a means for the mayor’s office to undermine the council’s legislative authority, resulting in governmental failure to help unhoused residents access long-term housing.

“This is all on executive,” Wonsley said. “Because there’s no plan, there’s been no intentional approach, and there has been no effort to actually collaborate with the legislative bodies to create a policy to guide how we view or support our unhoused neighbors in a humane way, we end up landing in this position.”

Frey’s office did not respond to the Daily’s request for comment.

The only planned legislative action on encampments is to receive a compiled report on them in March, according to Wonsley. In the meantime, encampment clearings will continue to be destroyed, local partners will work to distribute necessary survival supplies to people and unhoused residents will face another winter without additional help from the government, she said.

University response and resources for those facing housing insecurities

The University of Minnesota offers resources to students who may be struggling with homelessness or lack basic necessities, such as the Ending Student Homelessness Initiative, the Behavioral Consultation Team and referrals for students.

Students who are experiencing homelessness are referred to the Care Team run by the Student Affairs office at the University. The Care Team meets with students to talk about their living situation, work to figure out next steps and find housing for them.

One of the largest age groups that homelessness affects is 18- to 24-year olds. About 6% of students in the Minneapolis area from this age range found themselves experiencing homelessness in 2020, according to Charlotte Kinzley, a homelessness liaison for Minneapolis Public Schools.

At the University, 43.6% of students worry about their ability to pay for housing and 16.7% of students struggle with paying for their housing, according to the Undergraduate Academic Advising Center website.

“The high cost of housing, especially near our campus, adds significant strain to students’ budgets, forcing them to choose between rent, books, food and other basic needs,” according to the University Academic Advising Center website.

The University of Minnesota Police Department (UMPD) works with the MPD on crime around campus, including removing homeless people from campus. UMPD had no part in the recent evictions, according to Jake Ricker, public relations director for the University.

The Cedar-Riverside and House of Balls encampments sit a couple of blocks outside of the University’s West Bank campus. The House of Balls encampment is home to roughly 100 people, several of them young adults, according to Andy.

“I’m not aware of any instances where UMPD has worked with MPD on encampment evictions,” Ricker wrote in an email to the Daily. “We have not seen any significant encampments within UMPD’s jurisdiction and so there hasn’t been a need for any related actions, like evictions, from UMPD.”

Ricker added homelessness data is difficult to track through the University because many factors affect homelessness and UMPD’s police data does not specify which specific situations are classified under homelessness.

For more information on resources offered to students facing homelessness/housing insecurities, visit the Minnesota Department of Education website.

A Gopher

Dec 20, 2022 at 1:59 pm

What the article fails to address is the number of homeless who are choosing to be in illegal encampments because they do not like the sobriety rules imposed by the shelter system. These folks could be given shelter or homes right now, but unless they’re addictions are treated they wind up right back on the streets. Unfortunately, there are no perfect victims in this story and tolerating such behavior is no solution as anyone who uses the buses or light rail system can view the significant down turn in the quality and safety of those systems. Really, it’s an old tale, tolerate increasing lawlessness and become increasingly lawless. And before any of you NIMBYs downvote or comment think about what you or your parents would say if an encampment like this spring up on your suburban corner? I’m guessing you wouldn’t be offering them cookies and warm place to stay, would you?

Olga

Dec 17, 2022 at 11:58 am

This piece astounded me as one of the most humanizing, accessible, and well-written articles about homelessness/unsheltered people I’ve ever read. Well done, and thank you so much for sharing and shedding light on this situation and these people.