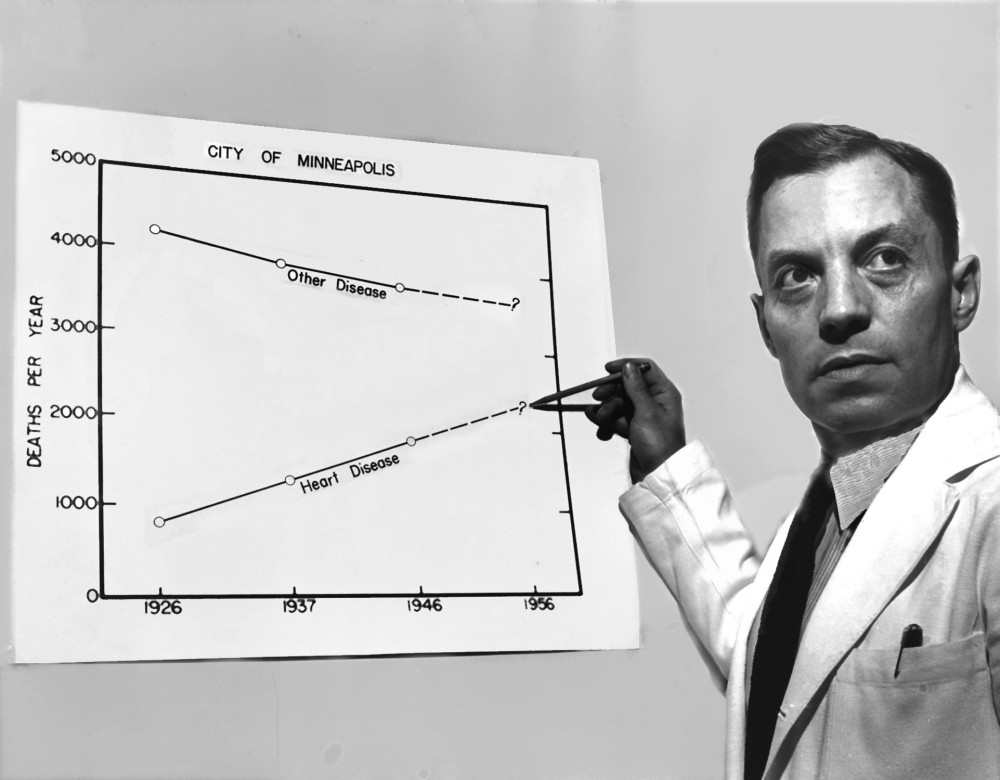

In 1957, Ancel Keys and a team of researchers embarked on an ambitious, global mission to reverse the heart attack epidemic through studying diet.

The University of Minnesota academic and his team traveled the world, from Japan to the Netherlands, testing men’s physical performance and collecting information about their diets.

Two decades later, Keys’ work was published in a landmark study – the Seven Countries Study. It evaluated a range of diets and was one of the first studies to pin cardiovascular disease, or CVD, to diet. The work helped define national nutrition guidelines today.

The study launched Keys’ already successful career into the stratosphere, and he became an academic celebrity. He made the cover of TIME magazine and emerged as the common person’s dietary guru, and his findings became nutrition science orthodoxy.

In recent years, studies accumulated that cast doubt on his findings, methods and prestige. The most damning result of his work, for some, is their claim that it played a role in creating the American obesity and diabetes epidemics.

The “Diet-Heart Hypothesis”

After Ancel Keys earned his Ph.D. in oceanography and biology in 1930, he worked briefly for the Mayo Clinic in Rochester before relocating to the University of Minnesota to found its Laboratory for Physiological Hygiene, which the War Department quickly conscripted for research work. He died in Minneapolis in 2004.

Keys’ interest in human nutrition was viewed as pioneering at that point, and his study in the halls beneath the University’s old football stadium on human starvation informed Allied Forces’ attempts to recover large portions of the war-torn world from malnutrition.

During this period, Keys made his name as the father of what would become nutrition science.

“But a big part of the public wants to know facts about diet and health. … The man most firmly at grips with the problem is the University of Minnesota’s Physiologist Ancel Keys,” the 1961 TIME magazine cover story said of Keys. “Keys’s findings, though far from complete, are likely to smash many an eating cliche.”

Keys’ Seven Countries Study became his most controversial and most important contribution to nutrition science.

Starting in 1957, Keys studied men from then-Yugoslavia, the U.S., Greece, Italy, Finland, the Netherlands and Japan and derived his famous “Diet-Heart Hypothesis,” – which states that people should eat less cholesterol and saturated fat to reduce cholesterol and resulting CVD – from the study.

Dissent and revision

Four decades passed before any researchers revisited his conclusions. Their criticisms have a growing foothold on the field Keys left behind.

“[The Diet-Heart Hypothesis has] certainly had a profound impact on the field … and really on the world because most countries follow our diet policies,” said Jeff Volek, a researcher in The Ohio State University’s Department of Human Sciences. “If you honestly look at the evidence, it continues to get weaker. There’s certainly no smoking gun studies out there that really support the Diet-Heart Hypothesis.”

Volek’s own research, started in the late 1990s, contradicts Keys’ frameworks. He found that those who follow low-carb, high-fat regimens are healthier and more resistant to diabetes. In some patients, this diet, paired with proper training, has even reversed Type 2 Diabetes, he said.

Professor Andrew Mente of McMaster University in Canada uses his background in epidemiology to study the effects of diet on certain biological metrics. He first stumbled on the Keys controversy after publishing a 2009 survey of nutrition research.

None of the data in Mente’s meta-analysis showed the same correlation between high-fat diets and negative health outcomes that Keys’ science would have predicted.

Mente has since studied Keys’ work closely and found Keys selected to study countries that would support his theories most intensively. He also identified issues with Keys’ methodology and the fact that it has not been replicated since.

Volek said the prevalent orthodoxy started by Keys made it difficult for him to launch his career, which has since included the publication of multiple research books and guides to low-carb living.

Volek said he faced pressures not to question the views held by most nutritionists. Deviation could mean trouble with peer review boards or even losing consideration from funding sources like the National Institutes of Health.

Mente said he didn’t face as much pushback, but he was cautious rolling out his findings at first. Today, the concern has lessened. He called the change a paradigm shift.

“I get a sense that the tide is turning and people are very, very receptive to the messages that are coming out from people like myself and others,” he said.

“There’s something wrong with our strategy”

While researchers like Volek and Mente have questioned Keys’ findings on saturated fats, work from reporters like Gary Taubes and Nina Teicholz paved the way for criticism in the media.

Articles in publications like The New York Times and The New Yorker have raised suspicion about the low-fat diet, along with the high-sugar, high-carb diets that fill the void fatty foods left vacant. Some of these lay the blame with the sugar industry. Some blame Keys.

Teicholz’s 2014 book “The Big Fat Surprise: Why Butter, Meat and Cheese Belong In A Healthy Diet” sharply criticizes Keys, his methods and his attitudes toward studies that contradicted his theories.

“The story is really one of personalities and politics and the players in the field. It is a story of people; people do science,” she said. “And if people let studies go unpublished or sit in NIH basements, those are stories of people.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control, more than one-third of adult Americans are obese, which contributes to some of the most persistently lethal ailments like Type 2 Diabetes and certain cancers, along with CVD.

The CDC also reported that, by 2015, over 100 million Americans over 18 had Diabetes or prediabetes. This is especially difficult to bear because of its cost to the health care system, preventability and lethality.

“If you were running a baseball team and you had 40, 50 years of complete losses, you would think, ‘maybe there’s something wrong with our strategy here.’ You would not describe that as progress,” Teicholz said. “You cannot look at the picture of health in America since 1965 and say that this has been progress.”

Still, Teicholz said her role in breaking up a long-established orthodoxy in the nutrition industry was vital.

“He really was on a frontier and many of the mistakes that he made or problems with his data were completely understandable,” Teicholz said. “I truly believe that he had absolutely the best intentions in mind.”

A paradigm shift?

Scientists and journalists with a range of views on Keys’ work and legacy have engaged in public dispute for the last decade, with critics questioning the scientific value of his work and others denouncing detractors’ stances as marketing gimmicks.

Henry Blackburn, who worked with Keys extensively during his research in the 1960s, said Teicholz and others ignore Keys’ legitimate contributions.

Blackburn, now retired, runs the University’s archival history of Keys’ lab and research. He said claims from Teicholz and others don’t come from the science community and are the result of underhanded attempts to sell books and faddish diet programs.

“I think they’ve used rather classical approaches of propaganda and repetition,” Blackburn said. “They’ve done it very carefully and rather deceptively and most of us are fairly sure it’s going to disappear eventually and Ancel will be re-established as the important scientist that he was.”

In August 2017, Blackburn coauthored a 64-page white paper defending the methods, data and conclusions of Keys’ Seven Countries Study, as well as Keys’ influence.

The paper claims Keys’ selection of countries for the study was valid, as the other nations in the data set would have been too influenced by Nazi occupation and the war to offer proper diet information. Plus, he chose countries with what he saw as the most contrasted diets to get the most variety in the study, Blackburn said.

But no one, including Blackburn, involved in the debate thinks Keys’ work is flawless.

Professor David Jacobs, who researches nutritional epidemiology at the University of Minnesota’s School of Public Health and knew Keys well, said the school has faced frequent accusations and complaints that it can’t be trusted since the push for low-carb diets began.

Jacobs said he studies food-based health, like how whole grains influence heart-health, and acknowledged there are problems with Keys’ research.

Diets should be prescribed based on the foods in them, and Keys too often researched and spoke about abstract nutrients while ignoring how they should be eaten. And while Keys’ research showed a clear delineation between the effects of saturated and unsaturated fats on health, his public advocacy often skimmed over such distinctions in order to reach more people, he said.

This conflation, Jacobs said, could very well have contributed to the American diabetes crisis, as Keys’ critics often claim.

“There are many people who are very good at selling their work and having good salesmanship skills when it comes to getting their message across,” Andrew Mente said. “I think what we need is … to better understand what the limitations of the Seven Countries Study are and raise awareness of those limitations.”

Jacobs said Keys’ work should be judged and criticized, but backlash against Keys and low-fat diets has been an over-correction.

“I don’t think the University of Minnesota and in particular, our department, has anything to be ashamed of,” Jacobs said.

David Reid

Mar 3, 2021 at 1:35 pm

Nobody is taking issue with some of Keys work. What should be a major concern is that he used confirmation bias, overlooked results that were contradictory to his theory, and was a bully. Many great minds like John Yudkin were attacked for postulating different theories. AT the least, Keys can be accused of bad science; at the worst, he has blood on his hands for shoving this low fat paradigm down the world’s throat. Clearly, the low fat theory has not decreased heart disease. We are fatter than ever in the USA and the world for that matter. Wherever the Western Diet show its ugly head, people get unhealthy. This entire topic needs to be reevaluated.