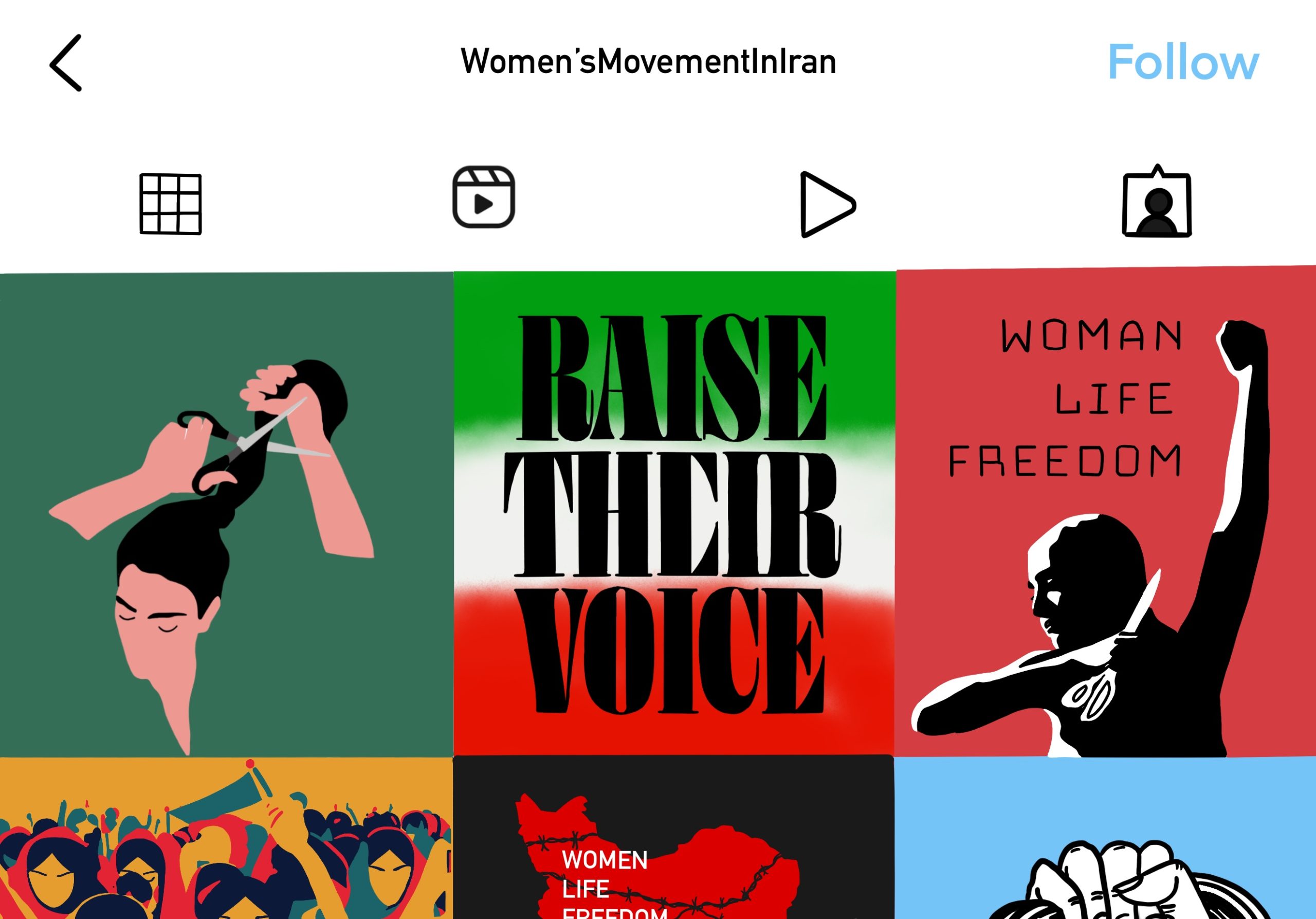

Since the death of Mahsa Jini Amini in 2022, Iranian women have led a women’s rights movement to advocate for gender equality and the expansion of women’s rights in Iranian society, which has gained global attention for its effective usage of social media.

On Sept. 16, 2022, 22-year-old Kurdish-Iranian woman Mahsa Jina Amini died in the custody of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s morality police. Despite Iranian officials saying she died of preexisting health conditions, her family maintains she was beaten to death by the police during her arrest for allegedly improperly wearing her hijab.

Hijabs were made mandatory when the Islamic Republic gained control of Iran after the Iranian Revolution.

On April 24, Toomaj Salehi, an Iranian rapper known for his outspoken criticism of the treatment of women and activists and the suppression of dissent by the Islamic Republic, was sentenced to death by hanging.

Salehi was arrested on Oct. 30, 2022, during protests after Amini’s death, according to a report by nonprofit activist group Human Rights Watch. He was beaten in custody and put in solitary confinement for months on end on numerous charges including “corruption on earth.”

Salehi was released on bail in November before his re-arrest days later after releasing a video speaking about the torture he endured in prison from the government’s intelligence agents.

The power of a platform

According to Yasmine Pahlavi, a prominent advocate for women’s and children’s rights and the wife of Reza Pahlavi, the former Crown Prince of Iran, the visibility of Mahsa Amini’s death struck a chord with an already outraged people.

“One thing that was certain was that her death was a spark for this new women-led revolution in Iran,” Pahlavi said.

According to Pahlavi, after the women’s rights movement was initiated, every Iranian she knew inside and outside of Iran felt compelled to speak up.

“We all did what we could in the positions we had and with the platforms we had to bring the voice of those inside suffering to the outside,” Pahlavi said.

The comments of Pahlavi’s Instagram posts, along with those of her husband, are flooded with calls for them to return to Iran.

“Wishing the best for you and the honorable people of Iran. Long live King Reza Pahlavi,” user Amir_shshirazz commented, accompanied by a crown emoji and two blue heart emojis under a recent post by Pahlavi on the Iranian New Year with her, her husband, her daughters and several other members of their family.

“The real faces of Iranians,” user Pezhvakariamehr wrote, with a red heart emoji under the same post.

Pahlavi said she does not feel the designation of the ongoing movement in Iran as only a women’s rights movement is as accurate, pointing to the young men who have died in support of the cause and other minority groups also being persecuted.

“That spark that started as a women’s rights movement morphed into what all of Iran and that society really wish for, which is human rights for everybody,” Pahlavi said.

Pahlavi said many of the people wrongfully detained by the Islamic Republic currently waiting in prison, some on death row, are artists who have used their platforms and artistic expression to speak out against the oppressive government, like Toomaj Salehi.

“They say that in Iran the prisons are like universities,” Pahlavi said. “Basically all of the intelligent, innocent, talented people are in prison.”

According to Pahlavi, social media has played a major factor in the movement by evading not only censorship by the Islamic Republic but also the editorializing of news often seen in the media.

Pahlavi added that the visual aspect of social media allows people worldwide to see evidence of what is happening inside of Iran instead of what is selectively shown at the discretion of cable news networks.

“My hope is that social media will help take the power that professors and the news media and politicians have over information and give it to people who can just for themselves firsthand see events unfold and make their own minds up, instead of being influenced by what someone wants you to think about something,” Pahlavi said.

Social media and raising awareness

Reporters Without Borders’ World Press Freedom Index ranks Iran as the fourth most information-repressed nation of the 180 countries surveyed. Only Vietnam, China and North Korea are positioned lower.

In the month following her death, #MahsaAmini in Farsi broke records, becoming the first tweet in the history of X, formerly known as Twitter, to have more than 250 million tweets, according to Data-Pop Alliance, a non-profit initiative aimed at analyzing data to address global challenges.

According to Sid Bedingfield, a professor in the Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication at the University of Minnesota, the development of social media has, to an extent, democratized media and had profound effects on the reach of social justice movements.

“In the old days, it was sometimes hard to find people who agreed with you. It was hard for you to understand or realize that there may be many hundreds in your own community or thousands across a region of the country who agree that something is a problem and should be addressed,” Bedingfield said. “Social media has made that happen instantly, across borders.”

While experts initially thought social media was going to equalize access to public discourse, Bedingfield added that with its rise as a tool for connection and information sharing, it became evident to adversaries of social movements that they could use these platforms to undermine them.

“There is concern that the Iranian women’s movement, facing an entrenched reactionary government that does not want to see this movement spread, finds ways to crack down,” Bedingfield said. “Some in the old-fashioned way, violence, throwing people in prison, killing people, but also in more subtle ways.”

Bedingfield said the spread of misinformation and disinformation on social media are potential ways oppressive governments can harness social media to sow dissent within a social movement, but added that social media still does give more access to information to people living in authoritarian or otherwise restricted societies than ever before.

“There was a time when authoritarian governments could shut down the flow of information, could control it,” Bedingfield said. “That sort of gradually eroded over time, and then, with the arrival of social media, fell apart.”

According to Bedingfield, the visual evidence of injustices has been critical throughout history in validating claims of social injustice to the public and will continue to be so until the threat of deep-faked images and videos becomes more widely accessible.

“The battle over public opinion is at the heart of almost all social movements,” Bedingfield said. “Now that battle is far more complicated because there’s so much more media.”

In solidarity with Mahsa Jina Amini and the women’s rights movement’s cause, hundreds of women and other sympathetic people in and out of Iran took to social media to show their support.

Videos of crowds chanting “Woman, Life, Freedom,” or, in Farsi, “Zan, Zendegi, Azadi,” the unofficial slogan of the movement, women cutting off their hair and burning their hijabs, and photos of rallies in support of the movement gained viral popularity in the weeks following Amini’s death.

Though media attention from the Western and global world skyrocketed after Amini’s death, this was not the first time social movements have been seen in Iran, nor did it mark the beginning of women’s rights activism within Iran’s borders.

The Islamic Republic

The Iranian Revolution of 1979 was an uprising that ended the previously standing monarchy, largely due to complaints of political repression and economic inequality, the resistance of Iranian citizens to modernization and perceived Westernization efforts by the former King Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi. This resulted in the declaration of Iran as an Islamic Republic, which promptly established a legal code based on Islamic law or sharia.

There is a debate among historians, activists, journalists and the Iranian public on whether the alleged involvement of foreign powers, including the United States and England, may have played a role in overturning the Pahlavi Dynasty for their own economic interests.

Harsh restrictions and regulations imposed by the Islamic Republic include the designation of crimes such as same-sex relations, adultery, non-violent drug and alcohol offenses and “insulting the prophet” as punishable by death. There are strict restrictions on freedom of speech for the public and the press.

Among the chief complaints by numerous human rights organizations, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, is the devaluation of the rights of women, certain ethnic and religious minority groups and LGBTQ+ citizens.

Women’s rights violations written in law include anti-abortion laws, married women’s legal inability to obtain a passport or to travel outside the country without the explicit permission of their husband and compulsory wearing of the hijab head covering.

A brief timeline of Iranian women’s rights and protests

After the revolution and establishment of the Islamic Republic and Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s election as president, the Family Protection Act enacted by the former king was abolished.

This action eliminated previously protected women’s rights, including the right to divorce their husbands, and lowered the age of legal marriage for women to nine years old.

In the 1980s, Iranian women were barred from serving as judges or running for presidential office and hijabs were officially mandated.

Women who had worn their veils in protest of the previously mandatory unveiling law under the Pahlavi dynasty’s reign began to protest when the law was overturned and the mandatory hijab law was enacted.

From 1989-97, President Rafsanjani’s government eased social restrictions on women, allowing them to initiate divorce proceedings and lifting some workplace restrictions on female employment.

From 1997-2005, President Mohammad Khatami passed laws temporarily easing restrictions for women, specifically improving access to higher education and women’s divorce rights.

From 2005-2013, President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad revoked many of these rights, restricting female access to higher education and employment.

In 2006, the “One Million Signatures for the Repeal of Discriminatory Laws” campaign was launched by women’s rights activists in Iran to protest discriminatory laws against women imposed by the Islamic Republic and advocate for change. Dozens of those who signed this campaign were arrested.

In 2017, young Iranian women started posting anti-government protests on social media under the hashtag #WhiteWednesdays, wearing white scarves before showing themselves unveiling in public.

During 2019-2020, in a period known as “Bloody November,” there was an outbreak of civil protests throughout Iran against the Islamic Republic, initially due to rising fuel prices. This was followed by a six-day-long total shutdown of the internet while the government worked to suppress the movement. According to Reuters, three anonymous interior ministry officials said that the death toll of activists killed during this time was “about 1,500.”

According to Human Rights Watch, the Islamic Republic’s police have raped, tortured and sexually assaulted detainees while repressing the widespread protests following Mahsa Jina Amini’s death.

Article 19, another advocacy group, estimates that during these protests, between 300 to 500 individuals including more than 40 children, lost their lives while thousands more have been detained.

Student perspectives on social media’s role in the women’s rights movement

An Iranian undergraduate student at the University, who requested anonymity out of fear of the safety of his family still in Iran, said that in order to escape mandatory military service, his family moved first from Iran to Germany and then to the U.S.

He said that while he was living in Iran, social rights were issues going on, but any public dissent was nothing compared to the extent of the protests after Mahsa Jina Amini’s death. Although he and his family have not attended protests or rallies in person, in or out of Iran, he said they have shared social media posts diligently.

“The good thing about social media is you get a lot of information from many different sources,” he said. “It’s not like if you just listen to the news, it’s just one source and they probably will tell you what they want you to hear.”

According to him, the plethora of Iranian-American celebrities in the U.S. has the potential to make a large impact on the movement’s reach by sharing information and testimonies from family and friends inside of Iran’s borders to their American friends and co-workers to spread awareness.

“Their co-workers and friends may not initially follow the news in Iran, but with someone being there and telling them that they should be aware of that, that can help,” he said.

He said social media has proven invaluable in breaking the recurring pattern where protests and citizen dissent on the streets are met by strict government suppression, only for protests to resurge again, a cycle that has previously stifled burgeoning social movements in Iran.

He added that the visibility of social and general news media has saved lives when people have taken to social media to protest unjust death penalty sentences, but has also done harm to the movement when people and news outlets post footage of protesters without blurring their faces or post graphic visuals of dead bodies.

“Graphic violence might not be suitable for everyone online. I think it’s not good for their families either, imagine a family has just lost their child and the father sees a photo of his child’s body all over the internet,” he said.

He said that in his opinion, a major difference between movements in the past and protests sparked after Mahsa Jina Amini’s death was the emotion behind them.

“After Mahsa, there was this rage inside, we’re like, ‘Yeah, okay, they’re gonna kill us anyway, so I’m gonna go out there and do my job,’” he said. “It wasn’t a sense of fear anymore after they were suppressed, it was a sense of rage, like people have had enough.”

Reza, an Iranian graduate student at the University, who requested partial anonymity for the safety of himself and his family still in Iran, said he does not feel he has earned the right to call himself an activist, despite his engagement with in-person protests and marches, as well as online information-sharing.

“In Iran, people die to be activists,” Reza said. “So, I’m not.”

Although social media and media attention are useful for spreading awareness, according to Reza, the Islamic Republic is now aware of its power. It has infiltrated social media to monitor what the public is focused on, using that distraction as a cover while morality police are sent to violently suppress protesters.

Reza said an example of this occurred recently when the Islamic Republic took advantage of the media coverage of Iran’s April 13 missile strike to crack down on protesters and other citizens not wearing their hijabs.

“The day after they attacked Israel, everyone started to speak about the attack. So the first thing that our government did was start to attack women in the streets,” Reza said.

According to Reza, another disadvantage of social media is the danger of creating a singular narrative about whose lives are important.

He said that while deaths in urban areas and hubs like Tehran make people such as Mahsa Amini into martyrs, there is little to no coverage of the deaths and crimes committed against activists in the more rural areas of Iran.

“In Tehran, everyone has the internet, everyone has a phone. But for example, in Zahedan or Balochistan, the situation there is really different. They don’t have a voice,” Reza said. “They are alone.”

According to Reza, the media can lack the attention span necessary to bring depth to discussions on social injustice. He said it is very important to not only see martyrs, such as Mahsa Jina Amini, as symbols of the movement but also to recognize them as people who are being mourned by their families and whose absence leaves a loss.

Reza referred to the people who have proudly posted photos with one eye looking at the camera and the other blindfolded after being shot by the morality police as living monuments to the movement.

He said that although the Islamic Republic had ordered its police force to shoot at sensitive areas on protesters as a way of igniting fear, it has had the opposite effect.

“For me, when I was reading these people’s posts on Instagram, it gave me power, to be honest. I wanted to go out again. I wanted to do something,” Reza said.

An Iranian doctorate student at the University, who has requested anonymity for the safety of herself and her family in Iran, said the power of social media is in giving women, especially from rural areas, a platform to utilize their voices in a society that otherwise diminishes them.

“It’s really important because, for the first time, women are at the center of everything,” she said.

According to her, social media helps build momentum for activists, citing the global solidarity found online due to viral clips motivating activists to keep fighting for equality.

“Sometimes there is just a very short Tweet or an image or a small part of a video that goes viral, and this shows people solidarity and passion and desire for equity and justice in this society,” she said.

She said while it is easy for global news audiences to remove themselves from the victims of crimes across the world, sharing the life stories of these victims on social media helps to humanize them, making it difficult for audiences to detach themselves.

On living in Iran, she said whether on the streets or in an academic setting, she notices a very prominent distinction in how she is treated compared to her male counterparts.

“Living as a woman in Iran is very hard because you feel that you are a secondary citizen, a secondary person,” she said. “That was one of the hardest parts of the story of my life in Iran, because I usually felt that I was not equal with men.”

Because of the societal restrictions on women, she said the act of living her life and pursuing academic advancement as a woman is both a protest against the Islamic Republic and a way for her to take back her autonomy.

She added that activities that may seem mundane to the Western world, such as driving a car, are a symbol of protest and empowerment for women in Iran.

She said although women are legally allowed to drive in Iran, women who choose to drive are greeted with harsh opposition from religious conservatives.

“Our activism is not departed or differentiated from our life. Our lives are connected to our activism,” she said. “Our life is part of our activism.”

Leila J.

May 1, 2024 at 3:43 pm

Thank you for raising awareness to the ongoing atrocities in Iran.

Outstanding article. Well written, comprehensive and insightful.

Jaleh

May 1, 2024 at 3:34 pm

Great article, Sam. You are an excellent writer and your piece was comprehensive and informative.

Mina M McKiernan

May 1, 2024 at 1:49 pm

Excellent article- so well-written and informative!

Linda S.

May 1, 2024 at 12:20 pm

Thank you, echoed.

Beth

May 1, 2024 at 9:18 am

Thank you for covering this important story with both a historical and current perspective. A special thank you to those who are from Iran for sharing even when their is implications and pressure not to.