What:âÄúCenter of the MarginsâÄù theater festival

When:Matinee and evening shows running until Nov. 27, see Mixed Blood website for details

Where:Mixed Blood Theatre, 1501 S. 4th St., Minneapolis

Cost:Free if you stand in line the night of a show, $15 for advanced guaranteed seating.

The âÄúCenter of the MarginsâÄù theater festival opened last weekend at Mixed Blood Theatre, featuring three plays by three different playwrights. The works all explored themes of disability and bias through the lens of love, but the results were disparate.

——————–

âÄúGruesome Playground InjuriesâÄù

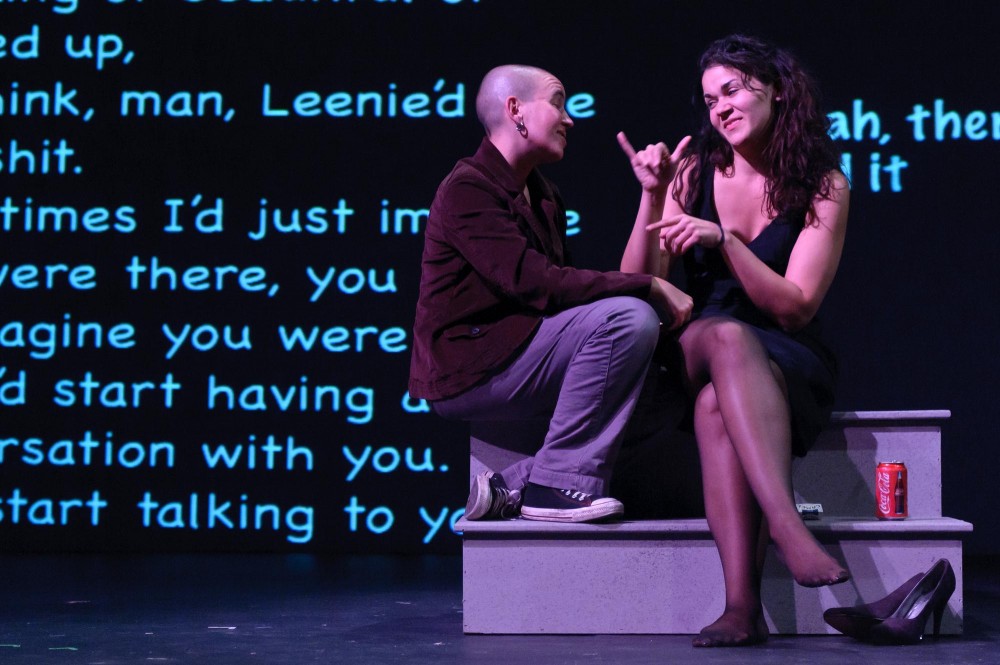

âÄúGruesome Playground Injuries,âÄù the first play in the festival, opens with a digital chalkboard tracing credits behind a dark stage. The craggy white lines explain that two characters just visible in the gloom will be somewhere between 8 and 38 years old as the play progresses and that their journey starts in a school nurseâÄôs office. The result of this explication is nebulous, denying the audience any ability to predict or categorize what might happen next âÄî forcing the mind away from expectations.

âÄúCenter of the MarginsâÄù is about denying expectations and driving the audience to deal with human nature on its own indescribable terms. The three plays showing at the West Bank firehouse theater share the common denominator of disabled characters but differ in the ways that those characters are presented fighting for agency in a world bound all around by invisible borders.

âÄúGruesome Playground Injuries,âÄù originally written by Pulitzer-nominated playwright Rajiv Joseph, was reinterpreted by director Aditi Kapil for two deaf actresses. The story follows Kayleen and Dag through time and space, mapping their hurricane love with the physical scars they gather. At times tender and brutal, the interactions between DagâÄôs stuntbird insanity and KayleenâÄôs neurotic self-loathing are blood-lettingly visceral.

Indeed, the adaptation from English to American Sign Language deepens this physicality, as the characters often push themselves to the point of breathlessness with their unflagging arms.

âÄúCasting two deaf women in a play about a hearing man and woman actually intensified the themes of the play,âÄù Kapil said.

âÄúMy Secret Language of WishesâÄù

âÄúMy Secret Language of Wishes,âÄù directed by Marion McClinton, is a distinct foil to the sparse, near-silent intensity of âÄúGruesome Playground Injuries.âÄù

Written by New York City-based Cori Thomas after she saw a young disabled black girl with her white caretaker on a subway platform, the play explores a custody battle between a poor white custodian and a wealthy black woman intent on adopting the younger charge.

All six members of the entirely female cast are invariably intense, from the high-octane lawyerwho brokers the situation to the crutch-bound Rose, who stands at the heart of the conflict. Even the lawyerâÄôs secretary is smart and capable, a strong woman who wonâÄôt take crap from anyone.

Pitting Rose and her feisty 24-year-old caretaker Dakota against the would-be adopter âÄî the âÄúmoney talksâÄù super-realtor Brenda âÄî the strength of the characters becomes homogenizing as the drama unfolds. Everyone in the play is overcoming personal demons while teaching their friends lessons, and in the process they become caricatures of frailty and success.

At one point there is a âÄúRockyâÄù-esque training montage as Jo the lawyer discovers different versions of her opening statement âÄî the final cut goes so far as to define love itself.

Thomas said that she did not set out to teach people about disability with her work but instead hoped to âÄúpaint people as far away from us as [she] could,âÄù and thus reveal the humanity inherent in difference. It is in that drive for differentiation that Thomas and the cast stumbled, however, becoming impressions of traits rather than full human beings.

âÄúOn the SpectrumâÄù

Ken LaZebnik experienced a similar desire to reveal humanity through extreme personalities when he wrote âÄúOn the Spectrum,âÄù commissioned and directed by Jack Reuler.

Ideas for the play were birthed in internet forums on the nature of autism, specifically on whether autism is a disability or a difference. LaZebnik began searching these sites when four close relatives were diagnosed as âÄúon the spectrum.âÄù

The play he eventually wrote features a 23-year-old man with AspergerâÄôs attempting to âÄúpassâÄù as normal after years of therapy. The man, Mac, eventually falls in love with a lower-functioning autistic woman he meets over the Web. The characters discuss perceptions of their âÄúdisabilityâÄù in terms of autismâÄôs actual effects, often highlighting hilarious inconsistencies in the thought patterns of âÄúnormalâÄù people.

At one point, Iris, the autistic woman, attempts to have Mac claim AspergerâÄôs as an asset on his law school application, telling him, âÄúWhile all of the other lawyers are wasting their time talking about feelings and families, you will be in the corner actually working.âÄù

Despite such confrontational moments, LaZebnik never intended it to be didactic in any way but instead hoped to show these two people falling in love. He wanted to make the audience question their own normalcy and discover the beauty of love no matter who gives and receives it.

However, the dialogue focuses so exclusively on the question of autismâÄôs effects and repercussions that the audience is constantly aware of the characterâÄôs condition. It is hard to get lost in universal love when it is framed by such a specific debate. At the same time, Iris has immense trouble with speech, causing her to speak at an agonizingly slow rate. Her first few lines are touching, but by the end of her monologues the entire crowd could be heard stirring in their seats.

———————

In the end, the small downfalls of âÄúMy Secret Language of WishesâÄù and âÄúOn the SpectrumâÄù subliminally function as a part of the âÄúCenter of the MarginsâÄù mission. When a playwright focuses too much on a disability (or a race or a class or a personality type), they can lose sight of a greater humanity and muddy their clear intent. Replace âÄúplaywrightâÄù in the above sentence with âÄúpersonâÄù and the universality of the mission becomes striking. The only play that was not originally written to showcase people with disabilities, âÄúGruesome Playground Injuries,âÄù is also the only one to successfully deliver its point of unconditional human affection. It is interesting that the play with only love at stake could effectively present love, while those with difference at their hearts could show only difference.