When describing the historical pattern of missing and murdered community members that motivated former roller derby player and Navajo activist Melissa Skeet to roller skate across the United States with a red handprint painted on her face, the name Matoaka came to mind.

She is known to many as Pocahontas, a Native American woman who fell in love with colonizer Captain John Smith in the 1995 movie of the same name. Indigenous activists remember Matoaka differently, as the first Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (MMIW) case.

“The first case was Matoaka. She’s what people perceive as Pocahontas from Disney’s perception of it, but really this young 14-year-old was the first MMIW case,” Skeet said. “She was taken from her home by the colonizers that came across the ocean and did the worst things to her and then later killed her.”

Hundreds of years later, Skeet’s cousin became one of these women, having gone missing before Skeet’s family found out she was murdered in Oklahoma.

Many missing Indigenous people are never found.

In October, “Skeet Fighter” completed a three-month-long roller skate trip from Washington State to Washington D.C., wearing a red handprint painted across her mouth to bring awareness to the MMIW movement. The entirety of it was documented on her Instagram account, @Skeet_Fighter.

Being a survivor of domestic violence herself and having a cousin who was reported missing and later found to be murdered, Skeet feels an intimate connection to the movement. She described her recent trek as both a healing journey and a burden she is proud to bear to support her people.

“Roller skating for me is my healing journey,” Skeet said. “The red handprint, it does exhaust me because you’re putting a lot onto your shoulders.”

The red handprint has become a recognizable symbol, identifying activists and those who stand in solidarity with the Indigenous community.

Throughout history, visual symbols have been used to identify social movements and create unity within them.

From Rosie the Riveter’s memorable stance with her sleeve pulled back and arm flexed representing U.S. women’s contribution to the workforce during WW2, now widely identified as a feminist icon, to the image of a raised fist and its long history with the Black Power, and Black Lives Matter movements, there are nearly as many iconic symbols as there are social movements.

According to Douglas Hartmann, a sociology professor at the University of Minnesota who specializes in social movements, symbols not only build momentum for movements but contribute to their legacy, helping them to be remembered beyond the pages of a textbook.

“It’s a way to kind of encapsulate messages in a quick way and then circulate that pretty broadly,” Hartmann said.

Physical representations of a cause are particularly useful with movements that have gained popularity outside of their original region as a nonverbal way to connect activists and create a sense of community that can transcend language and country lines, according to Hartmann.

Hartmann pointed to early Christianity as an example of this. In times of persecution, the symbol of the Ichthys, or the “Jesus fish,” helped Christians identify each other when they could not safely do so otherwise.

“I think any movement that’s broader than a few people, you’ve got to have a means to communicate and consolidate and coordinate people,” Hartmann said.

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women

Murder is a leading cause of death for American Indians and Alaska Natives, according to a report by the Centers for Disease Control.

In 2019, homicide was the fifth leading cause of death for Native American men and the seventh leading cause of death for Native American women and girls across the U.S., according to the report.

From 2010-2018, 8% of murdered women and girls in Minnesota were Native American despite Native Americans making up only 1% of Minnesota’s population, according to the Minnesota Department of Public Safety.

MMIW, began in Canada around 2015, according to the organization Native Hope. The MMIW movement is also referred to as the MMIP (Missing and Murdered Indigenous People,) or MMIR (Missing and Murdered Indigenous Relatives) movement to be more inclusive to men, two-spirit and otherwise non-female-identifying Native victims of violence.

The MMIW movement gained mainstream awareness in part due to videos of activists wearing red handprints gaining popularity on social media platforms like TikTok.

The movement has inspired legal action, changes in legislation and task forces working to identify root causes behind the disproportionate rates of murder and kidnapping in Native communities, especially among women and girls.

Videos often feature hashtags such as #mmiwawareness, #nativetiktok, #mmiw and #nomoremissingsisters.

Beyond the red handprint’s symbolic representation of the silencing and oppression of Indigenous communities across the U.S. and Canada, the color red has great spiritual significance to many Native people, according to Skeet.

Some Indigenous people believe that missing spirits living in the spiritual world can see the color red, and therefore the red handprint that activists wear. Skeet said she believes this helps the spirits of murdered Native people find activists they can trust to aid them in their journey for closure.

“Those lost spirits that just are basically lost, trying to find their way home, can follow this individual with the red hand print, allowing them to possibly be healed or bring healing to them,” Skeet said.

Naida Medicine Crow, the community outreach coordinator for the Minnesota Indian Women’s Sexual Assault Coalition (MIWSAC) said MMIR has been happening since colonization, something she is familiar with through her work with MIWSAC to address violence that affects Native communities.

“Our people, to be quite honest, are always on the back burner,” Medicine Crow said. “We’re still seen as not important, we’re still seen as invisible in the community.”

According to Medicine Crow, this stems from a colonized mindset that places a lesser value on Indigenous populations.

Medicine Crow has family and friends affected by missing relatives and has seen firsthand how law enforcement mishandles missing persons cases on and off tribal land.

“I’ve seen the hurt in the community, and I’ve seen the ones that just want to have a voice,” Medicine Crow said. “They’re not around here anymore, and they don’t have, you know, a voice anymore. So we have to stand up for them and try to do what we can for them.”

Medicine Crow said the symbol of the red handprint brought mainstream attention to the MMIW crisis, becoming a physical reminder of a harsh reality for Native communities.

“It’s definitely needed,” Medicine Crow said. “It is a representation of what’s happening in our communities.”

Free Palestine Movement

Since the Oct. 7, 2023 Hamas attack on Israel and subsequent war in Gaza, activists around the world began to call for a free Palestine and an end to what Human Rights Watch co-founder Aryeh Neier, a German-born Jewish holocaust survivor, said is a genocide during an interview with CNN’s Fareed Zakaria.

As of Nov. 13, 2024, Al Jazeera estimates the current death toll as 44,493 Palestinians and 1,139 people killed in Israel since Oct. 7, 2023.

Children accounted for 44% of verified victims over a six-month period, according to the United Nations Human Rights Office.

Protests at universities around the U.S., including the University of Minnesota, have been featured in the news, with student, alumni and faculty protesters asking for divestment from university endowments tied to Israel and increased attention by university administrators and officials on the war in Gaza.

At these protests, students have used significant visual imagery to raise awareness about the war, reenacting the dead, creating banners and notably, wearing keffiyehs, a traditional Arab head scarf historically worn by Bedouin men, a nomadic community in historic Palestine.

In an NPR article, Wafa Ghnaim, a Palestinian dress expert and a senior research fellow at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, said this headdress was first used in a political context in 1936 during the Arab Revolt in Palestine to conceal the identity of fighters.

At protests around the world and in the U.S., it is not uncommon to see protesters wear red, black or white checkered keffiyehs to express solidarity with the Free Palestine movement.

Keffiyehs have sparked controversy, some alleging they signify solidarity with Hamas or promote extremism because they shield protesters’ faces from identification.

This is reflected in comments in recent Minnesota Daily articles about protests on campus.

A group called New York United in Fighting Antisemitism petitioned for a ban on keffiyehs in New York City public schools, describing them as symbols of “hate and violence” and a form of intimidation against Jewish people, according to a New York Post article.

According to Hartmann, part of the importance of symbols in movements is their ability to create a distinction between those who are “in” and “out” of the movement.

Hartmann said symbols have to be somewhat polarizing because radical or meaningful activism always provokes strong negative reactions.

A Muslim student at the University and Free Palestine activist who asked to remain anonymous for personal safety said he wears a keffiyeh almost every day to be a constant reminder of the war in Gaza.

The student said while keffiyehs have now become synonymous with the Free Palestine movement, they were originally an expression of culture.

“All the different designs are symbols of the Palestinian image and like, its whole purpose was to keep the Palestinian culture and heritage alive and keep the identity,” the student said.

The student said he wonders if people with negative opinions on keffiyehs’ meaning have proof for their claims.

“If there is no evidence, then are you just intimidated by the idea of the Palestinian identity in general?” the student said.

According to the student, there is significance in each design aspect of keffiyehs, from the fishnet pattern representing Palestinian’s relationship with the Mediterranean Sea, olive leaf designs representing the resilience of the Palestinian people and bolded lines representing historical trade routes.

“It’s a way of, you know, keeping all the knowledge of Palestinian history alive within one design,” the student said. “And it’s a way for people to tell stories throughout each image.”

The student described keffiyehs as a way for Palestinians and those in solidarity to show a united front. He said when he sees someone wearing a keffiyeh, he is comforted in knowing they stand on the right side of history, for human rights.

Women’s Rights Movement in Iran

Roya Nazari, a master’s of fine arts student at the University, moved from Iran to the U.S. to pursue her degree in 2022.

Nazari originally intended to continue her visual study of mental health and environmental challenges in Iran. However, Nazari’s focus shifted when just a few months after moving across continents, the death of 22-year-old Kurdish-Iranian woman Mahsa Jina Amini in custody of the Islamic Republic of Iran’s morality police sparked a women-led revolution.

Amini was arrested after allegedly improperly wearing her mandatory hijab, and though government officials said her death was due to preexisting health conditions, her family maintains she was beaten to death by the morality police.

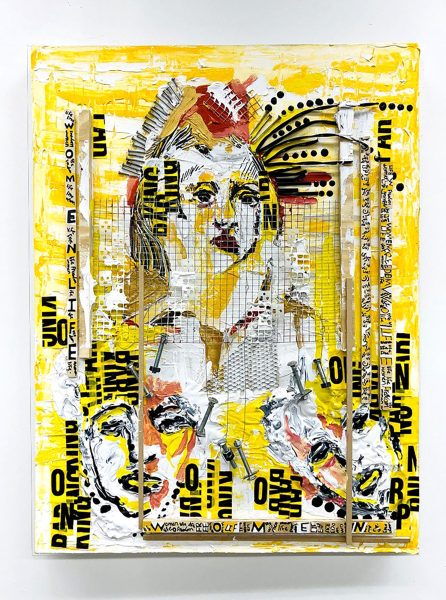

Now, Nazari aims to bring light to the conditions women face in Iran and the social movement there through her art by focusing on Iranian women’s performance as a tool for starting a revolution.

“I was thinking to myself, ‘Okay, I’m here as a free artist, and it’s my responsibility to explain what’s going on in my country,’” Nazari said.

According to Hartmann, because we are living in a materialistic world, movements need physical entities or objects to stand in for larger concepts and meanings to be more easily recognized and understood by the public.

“Things that symbolize, especially ideas of resistance movements, I think those make it tangible,” Hartmann said. “They allow it to carry further, give it a permanence and significance.”

A collection of Nazari’s art pieces will be on display at the Hopkins Center for the Arts in the sixth annual Iranian Artists Exhibition organized in conjunction with the Twin Cities Culture Collective until Dec. 1, 2024.

According to human rights organization Amnesty International, the Iranian government has been unrelenting in its crackdown on Women Life Freedom protesters. Research by the organization found government officials have used rape and other forms of sexual violence against detained protesters, including children as young as 12, and increased the use of the death penalty to subdue protests.

Following Mahsa Jina Amini’s death, hundreds of people in and out of Iran took to social media to show solidarity with the women’s movement in Iran. Marches and rallies were organized all over the world, including in Minneapolis.

Documented in social media posts and online videos, many women have been moved to cut off their hair and burn their hijabs to protest against the Iranian government’s “war on women.”

One of Nazari’s art pieces, “The Freedom,” features three locks of hair cut during one such demonstration, given to her by friends after attending a Woman Life Freedom protest in Minneapolis.

Nazari said she seeks out abnormal physical materials to use in her artwork that represent things she has had an emotional reaction to seeing on the news.

By doing this, she said she hopes to inspire curiosity in those who view her art, leading them to research the meaning of symbols such as cutting hair on their own. Nazari said the cutting of hair by activists has two meanings, the first being in protest of Mahsa Amini’s death, and the second emphasizing the importance of hair as a metaphor for something much more painful to lose.

“Hair, it doesn’t matter for us,” Nazari said. “We can cut all of our hair, it doesn’t matter. What we want, we actually want to have freedom.”

redroad

Nov 26, 2024 at 7:32 am

Informative, thoughtful article; thank you, journalists, for educating me. I especially appreciate how this article starts out with acknowledging, remembering and standing up for our missing and murdered indigenous relatives. I also love how roller skating is a form of healing. Thoughts and prayers up for Skeet and her family ~

GM

Nov 25, 2024 at 10:29 am

KG, very perfectly said. Sadly, there has always been a discrimination against the Jewish people and it has to be recognized and brought to the table. Thank you for pointing out what needed to be addressed here, especially on our U of M campus.

KG

Nov 23, 2024 at 2:57 pm

This extensive article on resistance symbols unfortunately omits the Jewish Star of David yet curiously includes the keffiyeh. While the Star of David appears on Israel’s flag, it has been associated almost exclusively with Jews and Judaism since the Middle Ages, with origins tracing back much further. Widely worn as a symbol of Jewish identity, it is prominently displayed on and in synagogues and Jewish institutions, and it signifies Jewish communal solidarity.

Especially after October 7, 2023, the Star of David has come to symbolize Jewish identity, pride and resistance against Hamas’ genocidal attack on Israel. On that day, heavily armed Hamas terrorists crossed the peaceful Gaza border into Israel, launching an unprecedented attack on civilians. They targeted a music festival, destroyed villages, and burned Jewish families out of their homes, either killing them or leaving them to perish in the flames. The atrocities included systematic rape, torture, the murder of over 1,200 people, and the abduction of 250 hostages into Gaza. Since then, Israelis have endured relentless rocket, missile, and drone attacks, displacing tens of thousands within Israel. Israel is fighting a war against Hamas terrorists, not against the Palestinian people. Full responsibility for the immense loss of life and destruction on both sides rests entirely with Hamas, which callously uses Palestinian civilians as human shields in Gaza and demonstrates blatant indifference to Palestinian deaths.

In the United States, the Star of David is a “red flag” for extremist Palestinians. Jews wearing or displaying the symbol have faced physical assaults, exclusion from businesses and public spaces, and social ostracism. At the University of Minnesota, Jewish students wearing Star of David jewelry have been harassed by classmates. In recent days, several incidents of intimidation and physical threats against Jews near Hillel have been reported to the MPD.

For Jews, the Star of David represents an enduring symbol of Jewish resistance, defiance, and identity. The Minnesota Daily should recognize and acknowledge its significance accordingly. Failing to do so would suggest a troubling bias.