Set to embark on what will be the most difficult year of his presidency, Bob Bruininks released the annual State of the University address on Monday, laying out his plan to navigate a stormy future. The University of Minnesota faces a budget shortfall of $132.2 million for the upcoming fiscal year and bleak projections for the foreseeable future. Left unchecked, the UniversityâÄôs annual deficit will exceed $1 billion by 2025. But with just 15 months remaining in BruininksâÄô presidency, his administration has limited time to send the University toward a sustainable future. Like numerous other public institutions, Minnesota is re-examining its priorities in an effort to decide which programs are vital âÄî and which can be cut. According to a September report from the Future Financial Resources Task Force, the University must âÄúnarrow the scopeâÄù of its mission if it is to remain viable in the increasingly competitive arena of higher education. Last fall, Senior Vice President and Provost Tom Sullivan sent a letter to the dean of each college, instructing them to create a âÄúblue ribbonâÄù committee. Among the questions Sullivan asked each group to consider: âÄúWhat programs should be discontinued or eliminated?âÄù In October, Bruininks established the Advancing Excellence Steering Committee, charged with guiding the decisions that will soon be made about the UniversityâÄôs future. In an e-mail obtained by the Daily, Bruininks told the committee, âÄúWe have just 12 months to 14 months to be prepared to publicly articulate our priorities and needs.âÄù Determining those priorities and needs is a task unlike any he has faced in his tenure at the University, Bruininks said in a recent interview. âÄúIt is the most challenging set of circumstances that I can recall in the 42 years IâÄôve spent here at the University of Minnesota,âÄù Bruininks said. The committees Beneath the noise of immediate and harrowing budget issues, faculty and administrators are building a plan that will serve the University beyond 2010. Recent actions have focused on trimming budgets and bolstering revenues, but they are only part of the solution. The most difficult decisions are still ahead, Bruininks wrote in his address. Minnesota is not dealing with a $132.2 million budget deficit because of junk bonds or hedge funds or the housing bubble. In fact, the administration has been preparing to stem the tide of diminished state and public support since it launched strategic positioning in 2004, well before the recession. The swift undertow of the economic crisis, however, now threatens to pull the University under. In September, the Future Financial Resources Task Force painted a startling picture for the Board of Regents regarding the UniversityâÄôs fiscal future. To balance the budget, spending cuts and revenue increases will have to total $1.1 billion annually by 2025, the report projected. Appropriations from Minnesota will yearly provide a smaller portion of the UniversityâÄôs operating budget, costs are significantly outpacing increases in revenue, and competition is stiffer in the state and nationally for a waning population of high school graduates, the report stated. With the immediate and lasting issues clear, Bruininks sent an e-mail to 23 University leaders establishing the Advancing Excellence Steering Committee. Working from the framework provided by the Future Financial Resources Task Force and populated primarily by administrators âÄî including 13 vice presidents and three deans âÄî the committee is focusing on a variety of areas, among them undergraduate and graduate education, the future of the health sciences, research and long-term financial planning. Bruininks laid out a threefold purpose of the committee: provide University-wide leadership, identify and address priorities and policy issues and communicate with units to ensure adequate consultation while sharing the results of the efforts of the committee. âÄúWe face difficult decisions involved in setting priorities, allocating limited resources and strengthening some academic programs while reducing, consolidating or eliminating others,âÄù the e-mail said. Around that same time, blue ribbon committees in every college were setting out to model a 2.75 percent budget reduction for 2010-11. They were asked to consider in their planning which programs should be maintained or strengthened and which should be dramatically reduced or eliminated. The recommendations were passed along to deans for use in ongoing annual budget discussions with the UniversityâÄôs trio of senior vice presidents. As they asked where things needed to be cut, however, the committees didnâÄôt always find answers. Computer science professor Joe Konstan was a part of the Institute of TechnologyâÄôs blue ribbon committee. As he went through the process of trying to find fat that could be trimmed out of the collegeâÄôs 2010-11 budget, Konstan ended up frustrated. âÄúWe looked at the data and said, âÄòWeâÄôre pretty lean, and weâÄôre doing really well,âÄô âÄù he said. Liberal ArtsâÄô âÄúCLA 2015âÄù was the only blue ribbon committee to publicly release its recommendations. It laid out $5.58 million of cuts, but no specific departments or programs were targeted. The CLA 2015 report released Feb. 1 directed its largest cuts to instruction, suggesting a $2 million reduction âÄî about one-third âÄî of vacant faculty positions and $1.53 million âÄî 5 percent âÄî of the budget for teaching and peer assistants. It was painful for Aria Sameni, the lone student representative on CLA 2015, to look at the data and realize cuts had to be made. Sameni said he regularly hears from students who are worried about how another reduction in faculty will affect their education. The committee reported to CLA Dean Jim Parente that the college could not sustain another round of cuts of the same magnitude and still continue to effectively operate all of its units. And the CLA committee was not alone. âÄúI came away feeling a big chunk of the solution isnâÄôt going to be deciding we can do things a bit more efficiently here or there, but deciding there are substantial chunks [of the University] that, as much as we can do them well, we just canâÄôt afford to do,âÄù Konstan said of his involvement on the IT blue ribbon committee. Urgency, transparency and consultation How the future of the academic landscape at the University will take shape is still unknown. When confronting questions as large as cutting or gutting entire programs or departments, some believe the process must be democratic. Others say the administration should make the difficult choices, but they still have doubts about whether the administration will be informed by adequate consultation. A number of faculty members fear for their programâÄôs safety, as they try to explain their value to leadership they are not convinced is listening. Provost Tom Sullivan said the Steering Committee is not a decision-making body, nor will it recommend individual programs or departments for reduction or discontinuation. Potential program changes filter through Sullivan regardless, with final authority designated to the Board of Regents. Sullivan said decisions will emanate from a groundswell, bottom-up process, but there are faculty members who wonder if their ideas will be given full weight. âÄúThe real question is âĦ will they be able to receive all of the information in all of its detail and subtlety at the top?âÄù asked William Beeman, an anthropology professor and faculty senate member. He said many in the senate classify the decision-making at the University as top-down, just the opposite of what Sullivan describes. âÄúThereâÄôs some suspicion among faculty members âĦ that many of the decisions will be made in a top-down manner and that the consultation is largely cosmetic.âÄù Bruininks said he and the administration are trying to hear all the voices. âÄúThereâÄôs a feeling if youâÄôre a faculty member or a staff member that this is all a big mystery,âÄù Bruininks said. âÄúMy voice doesnâÄôt count very much, but I want to assure people that is not the case.âÄù And yet, few at the University seem to have an idea of what, specifically, Bruininks and other leaders are thinking about the future. On March 25, the faculty senate gathered to discuss and vote on a 1.15 percent temporary pay cut for faculty and a mandatory three-day furlough for hourly employees. Konstan stood at a microphone, a single sheet of paper in hand, and calmly launched into a diatribe against the leadership of the University. âÄúIâÄôve heard some half-completed plans for the coming year âÄî plans that seem to keep changing,âÄù Konstan said. âÄúAnd IâÄôve heard that 2012 will be worse. âÄúI wish I had that trust in our leaders. I wish the last few years have convinced me that we had a vision and a strategy. But they didnâÄôt and I donâÄôt.âÄù KonstanâÄôs speech on March 25 accurately reflected the sentiment of many faculty members, said Chris Cramer, a chemistry professor and Faculty Consultative Committee member. âÄúThe decisions are really difficult, but at some point youâÄôve got to make some specific proposals, not just say, âÄòWeâÄôre going to use this to improve our excellence,âÄô âÄù Cramer said. âÄúOnly so many committees can meet before someone has to say something other than, âÄòLetâÄôs form another committee to study this.âÄô âÄù The call for transparency has reverberated from the faculty to the students to the staff. For Chris Uggen, co-chairman of the CLA 2015 committee, transparency is the ability to examine the cost of the spectrum of programs and services the University provides. âÄúIf things cost a lot to do, that doesnâÄôt mean we have to stop doing it,âÄù he said. âÄúWe just have to be aware and make a conscious decision.âÄù For others, transparency means periodic updates on specific ideas the leadership is considering. Cramer said the administration is forthcoming when asked for information, but theyâÄôre not always aggressive enough about disseminating potential proposals. WhatâÄôs clear is that time is running short. Bruininks said public universities are âÄúall in the same leaky boat.âÄù A number of other schools have already proposed or implemented significant program cuts. Michigan State University is currently evaluating the discontinuation of 49 academic programs. Deans, department chairs and faculty at the University of Iowa are weighing-in on 14 graduate programs identified by a provost-appointed committee, and Florida State University has already axed 13 programs. Konstan said he appreciates that Bruininks or Sullivan canâÄôt announce the closing of a college or program tomorrow, but he hasnâÄôt seen substantial progress toward balancing the budget in 2011, 2012 and beyond. âÄúNobodyâÄôs saying anything except for the fact that we have serious problems and theyâÄôre getting worse. My concern is with what weâÄôre going to do about that.âÄù The ‘new normal’ As long as the economy thrived and states were able to subsidize growth, schools were able to expand while simultaneously supporting programs that lacked enrollment or distinction. State support dipped in the early 2000s but rebounded to reach an all-time high in 2008. This time, the precipitous drops projected in state appropriations likely wonâÄôt be recouped for some time; Bruininks said they may never return to pre-recession levels. Some professors feel the rug has been effectively pulled from underneath universities across the country; schools are left to demonstrate their value to a public that may no longer be paying attention. This is the âÄúnew normal,âÄù Bruininks said. State support will become an ever smaller portion of the UniversityâÄôs budget. Beeman said the University should not capitulate. There is a grave danger in the defunding of public education, he said, and the institution should be at the forefront of the conversation. But the problem, said Chris Kearns, assistant dean for student services, is that thereâÄôs been a largely silent shift in attitude toward higher education. Once considered a public good, Kearns said, a college degree is now viewed as a private benefit. In addition, the University must compete for state money with Minnesota State Colleges and UniversitiesâÄô web of four-year, community and technical colleges that sprawl across the state. Before MnSCU reached all corners of Minnesota, the University was, by default, all things to all people. In the 1960s, when she was considering which college to attend, the University was basically the only public choice in the metro area, said Sen. Sandra Pappas, DFL-St. Paul, and chair of the Minnesota Senate Higher Education Committee. ThatâÄôs no longer the case. Students have options, and lots of them. State money for higher education is limited and dwindling, so the University and MnSCU will each have to decide where their institutions are strongest, Pappas said. The joke for years, Konstan said, has been that the University can ask for anything, and then it will get whatever MnSCU gets. ThatâÄôs an unproductive way to approach it, he said, and the state as a whole needs someone to talk about where thereâÄôs overlap and duplication. Kostnan admitted there may not be the political will for state officials to force campus or program closures. âÄúAlthough I do still think thereâÄôs a special place for undergraduate education, [the University is] not the only option,âÄù Pappas said. âÄúI think the U is going to have to focus a little more on the graduate and postgraduate fields.âÄù Whatever the reason for the stagnation of government money, the burden has shifted to students. In 2010, tuition overtook state support as the UniversityâÄôs largest revenue stream. In-state tuition surpassed $10,000 and has increased over 100 percent since 2001. When tuition increases offset decreases in state appropriation, the money isnâÄôt always plowed back to the students. In a February memo to Bruininks, the faculty senate committee on finance and planning said: âÄúIt also appears the added [tuition] money will be controlled by central administration rather than the schools and colleges. The increases will have to be used to offset state budget cuts and therefore will not be available for instructional purposes.âÄù Still, for the foreseeable future, tuition is the most promising candidate for bolstering revenue, according to the Future Financial Resources report. The gap between rising tuition and stagnated state money will likely only protract further. 15 months When Bruininks steps to the podium for his final State of the University address next spring, the Steering Committee will have finished its work and the University will be in the middle of constructing his successorâÄôs first budget. Bruininks said he doesnâÄôt want to kick the UniversityâÄôs fiscal woes down the road. Much can be done in 15 months, he said, and he wants to use all of his remaining time. âÄúWe cannot wait until âÄòthings get betterâÄô or until we have a new president,âÄù Bruininks wrote in his State of the University address. Bruininks has spent most of his adult life at the University and will return to teaching after his term ends. âÄúIâÄôm going to do everything I can, working with the academic community, to put this University in a stronger position to deal with the challenges and issues we have before us,âÄù Bruininks said of his remaining time as president. âÄúWe wonâÄôt get everything done, but I think we can get a lot done.âÄù

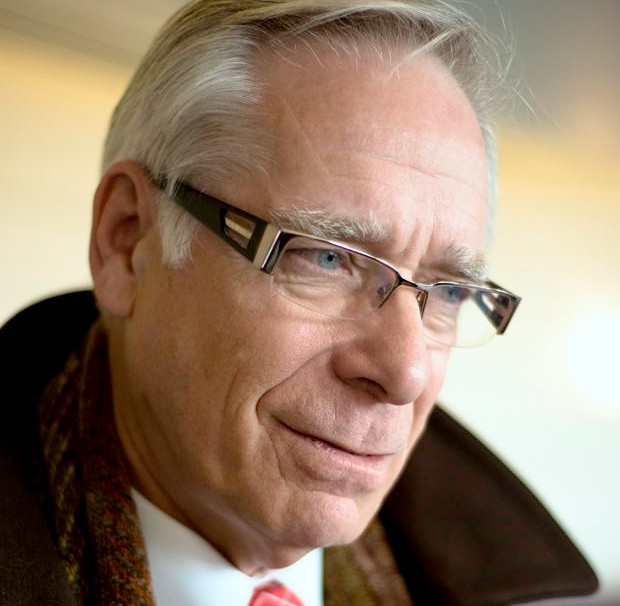

President Bob Bruininks said this is not a time for the University to retreat from its mission to become one of the top three public research institutions in the world.

Steering through the storm

The University faces a growing budget crisis. Time is short for President Bruininks and his administration to avoid the shortfall and decide the future of the school.

by Austin Cumblad

Published April 5, 2010

0