On the morning of June 26, 1926, John Allyn Smith Sr. allegedly shot himself dead outside his 11-year-old son’s bedroom window. John Allyn Smith Jr., later renamed John Berryman, would spend the rest of his life trying to make sense of his father’s death, plagued by the question: How could God do this?

Attempting to reconcile with the loss of his father, Berryman turned to sex, alcohol and literature.

“He was a searcher,” said Paul Mariani, a professor at Boston College and one of Berryman’s biographers. “He was looking for God, but he was angry with God.”

Berryman began teaching at the University of Minnesota in 1955 with help from friend and fellow professor, Allen Tate. During his 17-year residency at the school, he published most of his major works, including “77 Dream Songs,” which won the Pulitzer Prize in 1965.

But Berryman’s literary achievements couldn’t fend off his demons.

On the morning of Jan. 7, 1972, the 57-year-old poet lifted himself onto the railing of the Washington Avenue Bridge, waved to onlookers and jumped.

Four decades later, artists and aspiring poets, intrigued by Berryman’s tumultuous biography, are turning to him for inspiration.

Indie rock bands The Hold Steady and Okkervil River have written songs about him. James Franco is trying to make a movie about him. Al Milgrom is filming a documentary about his legacy. Peter Campion, the director of creative writing at the University of Minnesota, and Philip Coleman, a Trinity College Dublin professor, are planning a conference at the University for Berryman’s 100th birthday next year.

“There’s a group of younger people that I’ve heard from who are absolutely fascinated by this guy,” Mariani said. “Someone like James Franco says, ‘Yeah, this is America. This is something fresh, something new.’”

But the new generation might not be getting the full picture.

“It’s a little frustrating that these big issues — like suicide, alcoholism — kind of are masking all the things that he approached and wanted to understand,” said Berryman’s third wife and widow, Kate Donahue.

The slew of indie rock songs written about Berryman in the past few years don’t focus on his poetry and personality, but on his tragic death. The same is true for iconic poets like Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton and Hart Crane, whose names, first and foremost, bring suicide to mind.

“You think if he hadn’t done that, if he’d just died of natural causes or old age, how maybe people would be less interested in him,” said Brandon Stosuy, an editor at Pitchfork, an online music magazine.

Stosuy wrote an essay for the Poetry Foundation about Berryman’s influence on Craig Finn of The Hold Steady, who wrote “Stuck Between Stations” about Berryman’s suicide.

Stosuy said he found Finn was more interested in Berryman’s biography than his poetry.

“It had that feel where it’s a more cocktail-party understanding of an author versus, like, a really deep understanding,” he said.

Berryman’s legacy is similar to John Lennon’s in this way, Stosuy said.

“There’s a reason why people romanticize John Lennon over Paul McCartney,” he said. “Paul seems kind of cheesy, whereas Lennon gets killed, so he has this kind of saintliness around him.”

Richard Kelly, an early archivist for the University’s Berryman collection and a former student of Berryman, said he remembers the poet more for his enthusiasm towards teaching and writing than anything else.

“I think his suicide is one of the least important things about him,” he said.

‘I stand above my father’s grave with rage’

Berryman, born John Allyn Smith Jr. spent his first 10 years in McAlester, Okla. In 1925, his parents moved the family to Tampa, Fla., hoping to profit from the land boom there.

The effort failed, and the relationship between Berryman’s mother and father grew increasingly hostile. Martha Little Smith began seeing a wealthier man, and John Allyn Smith Sr. spiraled — drinking and smoking his problems away, just as his son would decades later. Within a year, Smith Sr. was dead.

“There’s been some conjecture that [Berryman’s] father [didn’t commit suicide], but was murdered by his mother and future stepfather,” Peter Campion said.

Ten weeks after Smith Sr.’s death, Little married John Angus McAlpin Berryman, whose surname was given to the 12-year-old Smith Jr.

This was the platform on which Berryman’s life was built, the experience that would haunt and inform his life and work.

“It almost breaks my heart to think about it because he lived with that his whole life, and the No. 1 predictor of suicide is a parent who committed suicide,” Campion said.

Berryman first tried to kill himself in 1931 by throwing himself onto train tracks after a fight with a classmate at South Kent School in Connecticut.

His interest in writing was born at that same school. As the smallest student in the youngest grade, Berryman couldn’t play football, so he instead opted to write about it for the school’s paper, “The Pigtail.”

In 1932, Berryman enrolled in Columbia University. He realized his love for literature and poetry, and his work was published in the Columbia Review in 1935, a year before he graduated.

But despite his small successes, Berryman achieved national acclaim much later than his friends and peers.

Those who knew him said he was bitter toward critics, and he wasn’t afraid to

acknowledge it.

“It was just that I had no skin on — you know, I was afraid of being killed by some remark,” Berryman said in an interview with the Paris Review in 1970.

He finally gained national recognition in 1956 with “Homage to Mistress Bradstreet,” an epic poem about the life and work of North America’s first published poet, Anne Bradstreet.

Berryman knew he deserved the attention, and he was particular about his public image. When Paris Review asked how Berryman reacted to being labeled a confessional poet, he responded, “With rage and contempt! Next question.”

‘These songs are not meant to be understood, you understand.‘

Berryman published 11 books of prose and poetry while he was alive, and four more were published posthumously. He wrote most of his best-known work, “77 Dream Songs,” while he was teaching at the University.

“I read the ‘Dream Songs,’ and they immediately captured my attention,” said Paul Mariani, a Berryman biographer. “The more I read them, the more I wanted to know about them.”

Berryman became fixated on dreams while undergoing psychoanalysis for his alcoholism and suicidal tendencies.

“It’s as though you were kind of in a twilight zone or in between two worlds,” Mariani said of the Songs.

Henry, the main character in “Dream Songs,” is a white man, sometimes in blackface, conversing with a character named Mr. Bones.

“[Berryman] registers different voices and ways that people speak that aren’t usually considered poetry,” Campion said. “Set in the right context, they can become high art.”

Berryman’s approach impacted poetry in the same way jazz impacted music –– it shook things up and stuck.

“Those civilized safeguards were out of the way,” Mariani said. “And that’s what Berryman’s looking for — get rid of those and say what’s on your mind.”

By doing so, Berryman secured his importance.

“Berryman could put that trumpet to his lips and blow, as it were, and it was just extraordinary,” University of Minnesota professor Emeritus Michael Dennis Browne said.

‘Madness & booze, madness & booze’

Berryman married three times, had three children and taught at 10 schools in his 57 years. He was a serious alcoholic, frequently hospitalized for intoxication toward the end of his life.

Mariani said he first became interested in Berryman while writing a biography about Berryman’s friend and fellow poet, Robert Lowell. He set Lowell aside and plunged into Berryman’s notoriously troubled life instead.

“It was like touching an electric wire very often,” Mariani said. “I find myself saying again and again, ‘Don’t do that, John. Just don’t do that. That’s not gonna work.’”

Berryman married his third wife, Kate Donahue, in 1961. She was 22 and he was 46. Donahue said Berryman’s alcoholism impacted his health more and more as he aged.

“He was drinking a bottle of whiskey a day, just because that’s what he needed to bring him back to what felt normal,” she said.

In Berryman’s time, alcoholism wasn’t understood like it is today. For years, Berryman thought he was suffering from exhaustion when, in reality, the booze was making him sick.

“I could never quite figure out what he was going to the hospital for, and really it was to get him away from drinking,” Donahue said. “But nobody put a label on it.”

Berryman developed a pattern of getting drunk at local bars, checking himself into the hospital and calling a cab in the morning when it was time to teach, Mariani said.

Then he’d do it all over again.

“He would come to class sometimes shaking, and you could see that he’d had a hard night,” said Berryman’s friend and former student Judith Healey. “But he never lectured in a less than brilliant manner.”

Many of Berryman’s students, including the award-winning memoirist and University professor Patricia Hampl, didn’t realize what the drinking was doing to him.

“We didn’t have the wit or intelligence or training to understand how sick he was,” Hampl said. “In those days, alcoholism and inspiration kind of went together.”

Richard Kelly, the archivist and former Berryman student, said he never saw Berryman acting out of control when he was drunk.

“It seemed like it almost made him more lucid in a way,” he said. “It would maybe unloose or unwind him or something.”

Browne, who hosted a Berryman celebration in 2011, said Berryman’s habits were considered fascinating in the 1960s.

“He was, you know, a kind of archetypal, horny, drunken poet of an earlier time,” he said. “That’s not the image of the poet that we particularly admire or follow these days.”

‘Industrious, affable, having brain on fire’

Berryman came to the University of Minnesota after he was arrested and fired from the University of Iowa’s Writers’ Workshop for drunkenly defecating on his landlord’s front porch.

While at Iowa, Berryman taught a group of poets who would go on to achieve widespread acclaim, including W.D. Snodgrass, William Dickey, Donald Justice and Phillip Levine.

Berryman found a dedicated student following at Minnesota as well. Since the University lacked a creative writing program at the time, students relied on Berryman’s support for their poetry.

Outside of class, Berryman would invite students to meet him at his home or local bars, where he’d read and critique their work.

“To sit at his feet and to have him read your work was a big deal,” Hampl said.

Berryman treated his classes like performances. He read theatrically, often gesturing wildly with his cigarette and bringing students to tears, Hampl said.

Once, Berryman threw a chair across the classroom to get people’s attention, Kelly said.

“[He said] good teaching is partly theatrical, and you imitate the best prof you ever had,” Kelly said.

But the combination of teaching, writing and drinking eventually took its toll.

“He just kind of wore himself out,” Kelly said. “Towards the end, he kind of felt the writing and the teaching weren’t going that well.”

‘Then came a departure’

In his last years, Berryman started in Alcoholics Anonymous at the encouragement of a priest who led a therapy group he was in.

The chaplain even offered to take over teaching Berryman’s classes, Mariani said. “That’s what he was looking for –– somebody to care.”

Berryman worked the program’s steps, stayed sober for 11 months and wrote a veiled autobiography called “Recovery.” But the levee couldn’t hold.

“After John got sober, I think the tortured nature of things that had happened when he was younger came back,” said Healey, Berryman’s former student and friend.

The booze had been a buffer between Berryman and his past. When sober, he was forced to face his demons. Try as he might, he couldn’t reconcile with himself or with God.

“He was a sinner,” Donahue said. “And he didn’t feel like he had a way back into a spiritual relationship.”

Days before he jumped off the Washington Avenue Bridge, Berryman relapsed.

“In the end, he finally picked up a bottle, drank and said, ‘Oh boy, that’s it,’” Mariani said. “I think he just did not want to be a burden anymore to his family.”

Donahue and Berryman’s daughters, Martha and Sarah Berryman, were 10 years old and 7 months old, respectively, when their father died. They still live in Minnesota.

Kate Donahue lives in the same house she bought with Berryman more than four decades ago and spends her time teaching poetry to local children.

“I don’t live a Berryman life,” she said. “I live a Donahue life because I’m a happy person.”

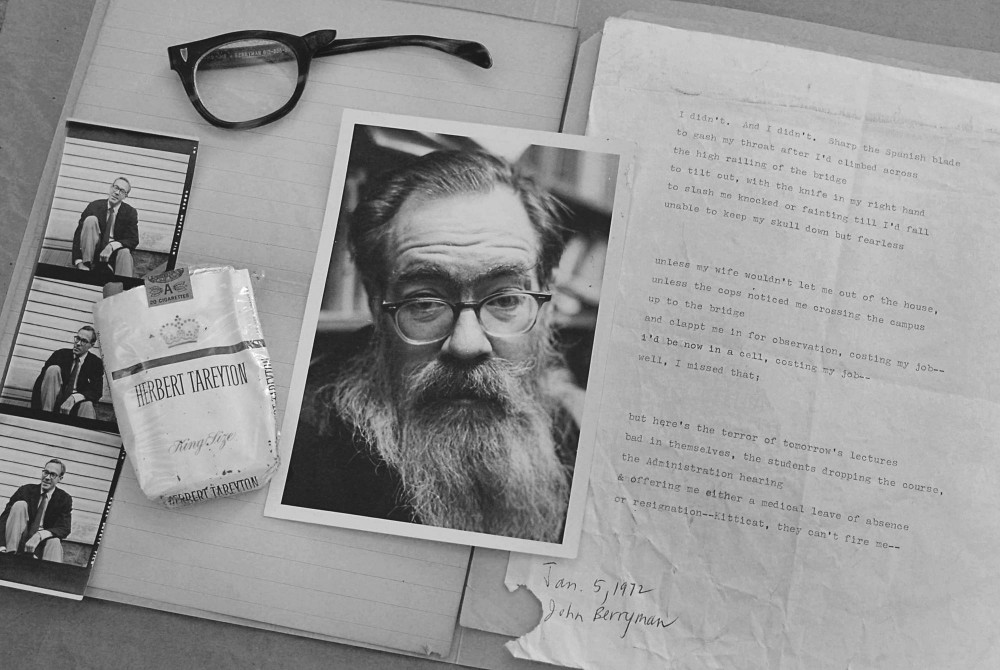

In her dining room, shelves of books written by and about her late husband line the walls. Nearby, one of her favorite photographs of Berryman is propped on a table.

The picture shows Berryman seated next to a foot-tall stack of papers –– the original “Dream Songs.” His expression suggests he’s trying hard to conceal his pride.

“He loved the truth and wanted to find it,” Donahue said. “And like everybody else, he fell a little short.”

Brian Mullally

Dec 31, 2024 at 7:12 am

John Berryman lived in Ireland for a short while in 1966 I think.

He befriended my father in a local Pub and my father invited him around to our house over Christmas with his wife Kate and daughter Martha, I was a little older than Martha at the time.

He gave my father a gift of a book Letters of the great artists. He wrote a beautiful inscription thanking my father for his generosity, his handwriting was lovely.

Thankfully I still have the book.