University of Minnesota researchers have found that two cancer drugs combined in pill form can be used to fight HIV.

The research, published Aug. 30, still has a long road ahead before the pill can be tested on humans — a road that will take years to travel.

“The road is littered with the carcasses of failed drug treatments,” said Dr. Keith Henry, director of HIV research at the Hennepin County Medical Center. “Most fail, even if they look good in theory.”

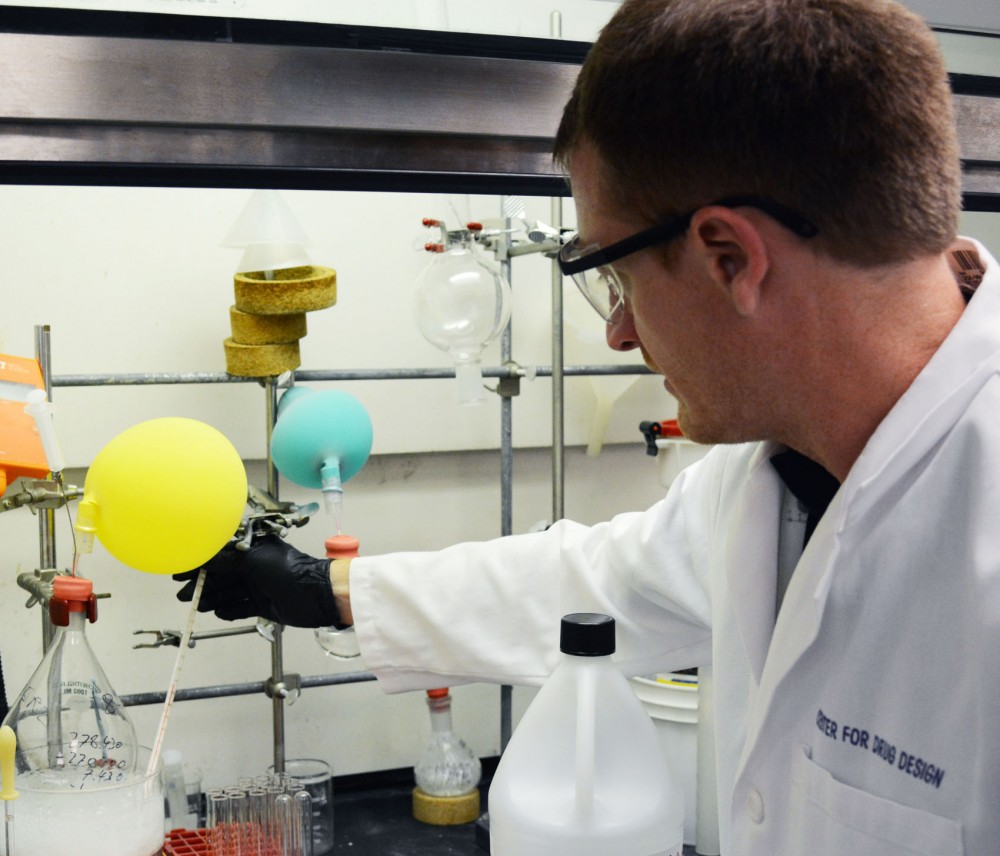

But Steven Patterson, associate director of the University’s Center for Drug Design, and one of the scientists who worked on the project, isn’t worried.

“We’re very optimistic about clinical translation,” he said.

Last week, the National Institutes of Health gave the team a $2.3 million grant to continue its research for the next four years.

The University has a lucrative history of HIV research. Ziagen, an HIV-fighting pill, has garnered more than $600 million in royalties since University researchers designed it in the 1980s.

Now, that money helps fund new projects like Patterson’s in the Center for Drug Design.

A $50,000 seed grant from Ziagen royalties originally funded the project, said Robert Vince, the center’s director and one of the researchers who developed Ziagen.

The cancer drugs are normally given by injection, Patterson said. But because other HIV drugs are available in pill form, he said, he doesn’t think patients would be interested in an injected drug.

The study confirmed the drugs could be taken as a single pill. With this discovery, Patterson said, he’s confident it will be useful for people with HIV.

The drugs increase the number of mutations as the virus reproduces, making the new viruses defective, he said.

Because other HIV drugs on the market work differently, this approach may help patients who haven’t responded to treatment, Patterson said.

The next steps will be to test the safety and effectiveness of the drugs on animals before starting human trials.

Henry said the new research is intriguing, but added there’s a big leap between the lab and use in humans.

“It takes a lot of money and time to introduce a new drug,” he said. “A lot of people try, and most people fail.”

Developments in HIV research

Even with the many failures, HIV treatment has improved dramatically in the past few decades.

Initially, HIV medication was “pretty nasty,” Henry said.

Patients had to take the first HIV pill, AZT, every four hours, even at night.

“It was a nasty medicine overall by today’s standards, and modestly effective,” Henry said.

Now, he said, many pills on the market only have to be taken once a day.

HIV targets a patient’s T cells, which the body uses to fight disease.

The virus invades a T cell and uses it as a “factory” to create new viruses, usually destroying the T cell in the process and resulting in a suppressed immune system.

The virus spreads through bodily fluids, including through sex, blood transfusions or sharing needles. Henry said cleanliness in medical centers and the common practice of testing people for HIV before transfusions have considerably diminished the risk of blood exposure.

Nearly 80 percent of Minnesota students report being sexually active within their lifetime, but only 0.2 percent report being diagnosed with HIV or AIDS in their lifetime, according to Boynton Health Service’s 2012 College Student Health Survey.

With ongoing research like Patterson’s, Henry said, it’s possible for HIV patients to live relatively normal lives.

“The treatment has improved impressively,” he said.