Over the weekend, Prince fans flocked to First Avenue in downtown Minneapolis and the musician’s home, venue and recording complex Paisley Park in Chanhassen, Minn., to pay homage to the Minneapolis-born artist.

The Eiffel Tower, San Francisco City Hall, the Chicago skyline and the I-35W Bridge were illuminated in purple light as a nod to his hit “Purple Rain.”

The 57-year-old was found unresponsive on Thursday in an elevator at Paisley Park, and authorities have yet to release a cause of death. Close friends and family of the musician gathered Saturday for a small private funeral.

The eccentric singer produced 39 albums, winning seven Grammy Awards and an Academy Award for best original score throughout his decadeslong career.

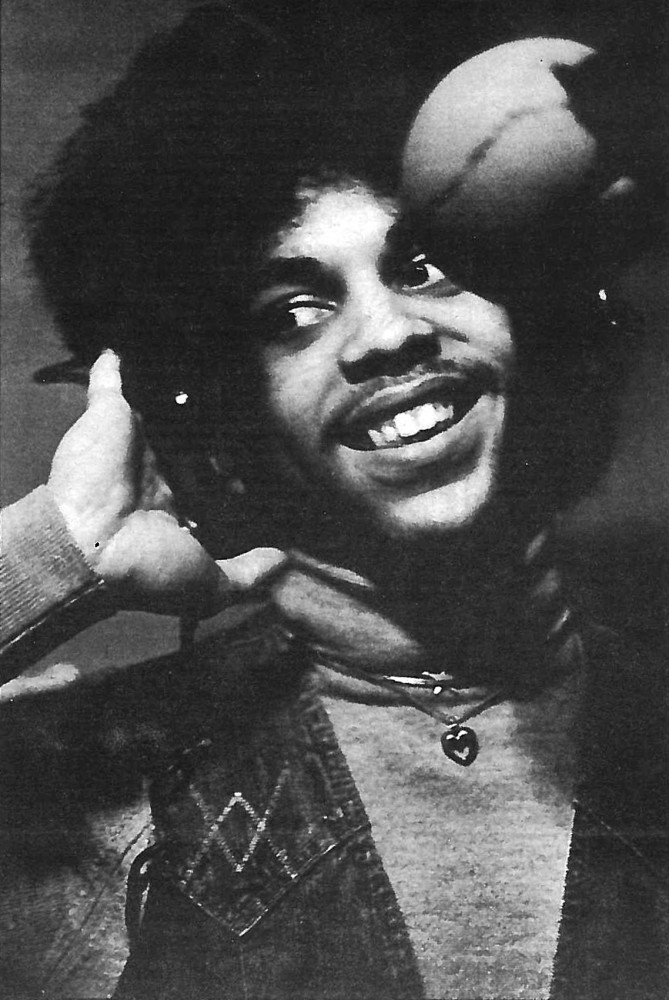

In 1977, before his meteoric rise, the Minnesota Daily’s Lisa Hendricksson interviewed an 18-year-old Prince about his creative process and ambitions.

The following is her original article in its entirety:

The American recording industry isn’t exactly glutted by musicians from Minneapolis. The few who do make it big internationally, like Leo Kottke and Michael Johnson, are firmly embedded in the acoustic folk tradition that defines the Minneapolis music scene.

With the flowering of the sophisticated, well-equipped Sound 80 recording studio, all that may change, however. Acts as diverse as Cat Stevens and KISS have recorded there, and local bands like Lamont Cranston are cutting albums. Clearly, Minneapolis is beginning to break free from its folk-oriented roots.

If he makes it, the most atypical local star to come out of Sound 80 will be a multi-talented [18-year-old] prodigy from North Minneapolis who plays any instrument you hand him, sings with a crystal pure falsetto that would have put the young Michael Jackson to shame, and goes by the name Prince. No last name, and please, no “the” prefix. Just Prince.

If you haven’t heard of him yet, you’re not alone, though you may have danced to rough mixes of his songs (without knowing it) at Scotties. Right now, Prince is probably the best-kept musical secret in Minneapolis, known mainly to local session musicians and recording studio habitués. The reason he’s not already a well-known local performer is simple: ambition. This kid wants to be a major national recording star, and the way to do that is not to wear out your vocal cords at the Tempo night after night. A smart, anxious [18-year-old] isn’t going to sit still for a lecture about paying dues, either. He’s got his program pretty well worked out, and the wheels are in motion. From where he and his manager are sitting, it’s only a matter of time.

Prince is making an obvious effort to hide his impatience the night I visited him during a recording session at Sound 80 a few weeks back. The WAYL [radio] Strings were trying to lay down a not too difficult track that Prince had written, and the 16th notes were coming out like mush. They plugged away for about an hour when Prince very politely told the conductor to change the 16th notes to quarter notes. This done, he slumped down in his seat, looking dissatisfied and slightly annoyed. “We won’t be able to use that. I hate wasting time. I want to hear that song on the radio.”

It’s a little startling, hearing this from a teenager, albeit an extraordinarily talented and self-possessed teenager. But when you begin playing piano at six, guitar at 13, bass soon after, and finally master the drums at 14, your time schedule gets pushed forward a bit.

Prince was spotted playing in a high school band by Chris Moon of Moonsound, another, smaller local recording studio. His excellence was immediately apparent, and Moon began collaborating with him in the studio, putting together tapes. With several songs in the can, Prince headed for New Jersey to find fame and fortune by way of Atlantic Records. The people of Atlantic, though impressed, suggested that his sound was “too Midwestern” — whatever that means. Others, notably Tiffany Entertainment, a company owned by basketball player Earl Monroe, made offers which Prince apparently could refuse, because by winter he returned to Minneapolis.

Things got back on the track in December when Prince’s tapes made such a big impression on former Twin Cities promoter Owen Husney that Husney decided to come out of comfortable ad agency anonymity to manage Prince. Together, they’ve spent the entire winter in Sound 80, polishing the production on the three or four songs they intend to present to all the major labels in [Los Angeles] next week. Husney is confident about Prince’s chances for a contract, citing the capriciousness of the record business as the main roadblock. With typical managerial optimism, he says, “If he isn’t [signed], it’ll be because somebody’s wife burned the eggs that morning.”

How much basis is there for this optimism? A great deal, I think. For one thing, Prince has two valuable gimmicks going for him — his age and his versatility. Not only does he play every instrument on the Sound 80 tapes, he also does all the vocal tracks and has written and arranged all the songs himself. It’s a prodigious feat, made all the more impressive by the fact that he’s self-taught. Although his father was a jazz musician, Prince insists that he didn’t actually teach him anything, nor did they play together very often. He seems to have gotten the ability by osmosis.

Another strong point is the obvious commercial appeal of his sound. It’s sweet, funky disco soul, but I’ll de-emphasize the “disco” because the arrangements are more sophisticated and inventive, less formulaic than the simplistic repetitiveness one associates with disco. His use of a driving synthesizer on one song, “Soft ’n’ Wet” is traceable to Stevie Wonder, and his phrasing derives a little from Rufus’ Chaka Khan. If he hasn’t totally transcended his influences, he certainly has assimilated them convincingly.

The development of this pop sound troubles Prince a little. He has spent his adolescence around good musicians and understands the value of respect. Ideally, he says, he would like to record jazz on one label under a pseudonym and the pop stuff on another label.

Finally, there is Prince’s personal appeal. As a performer, he should have little trouble. Not only can he jump from instrument to instrument, but he’s the kind of cute that drives the boppers crazy. He’s not adverse to choreography, but draws the line at spins. “I get nauseous,” he explains.

In an interview situation, he’s quiet, even aloof, with a sly sense of humor and a quick, intelligent smile. You get the feeling that not even at gunpoint would this kid make a fool of himself in public. Before I talked to him, his manager assured me he didn’t use drugs or alcohol and wouldn’t jive with me. I actually believe the former, but not the latter. Jive takes many forms, and this cool [18-year-old] has it down to a subtle art.

After the recording session everyone went out to Perkins for coffee. Tired of having to act twice his age for the elderly WAYL gang, Prince ordered a milk shake and began adding things to it — ketchup, blueberry syrup, honey, steak sauce, coffee, jam, salt and pepper. He ordered the waitress over to the table and handed her the concoction.

Opening his large brown eyes even wider, he said, “I think there’s something wrong with this. It tastes funny.” The worried waitress asked what it was supposed to be and hurried over to the manager, who formally apologized and took it off the bill. Prince brought off the whole scene with a royal aplomb befitting of his name.

What a relief. Earlier in the studio, I was sure he was a clone, constructed in the back rooms of Owen Husney’s ad agency. Prince is a real live kid, packed with talent, but basically normal and mischievous. Besides his music, that was the nicest surprise of the evening.

Editor’s note: This story was written by Lisa Hendricksson and was originally published April 8, 1977. Certain parts of this story were edited for clarity. The story appeared on page 3AE with the title, “Prince.” The Associated Press contributed to the information in the preface to Hendricksson’s story.