Forty years after his expeditions to Antarctica, Akhouri Sinha discovered he had made a more permanent mark on the continent than he knew.

Sinha, a University of Minnesota adjunct genetics, cell biology and development professor and a research scientist at the Minneapolis Veterans Affairs Medical Center, spent 22 weeks in Antarctica during the early 1970s as part of the first team of explorers to catalog vital data on the animal population there.

A few years later —unbeknownst to Sinha — the Advisory Committee on Antarctic Names doled out a distinct honor when they dubbed a 990-meter mountain after him.

He’s since found out there’s a mountain carrying his name, but that hasn’t given him reason to stop working.

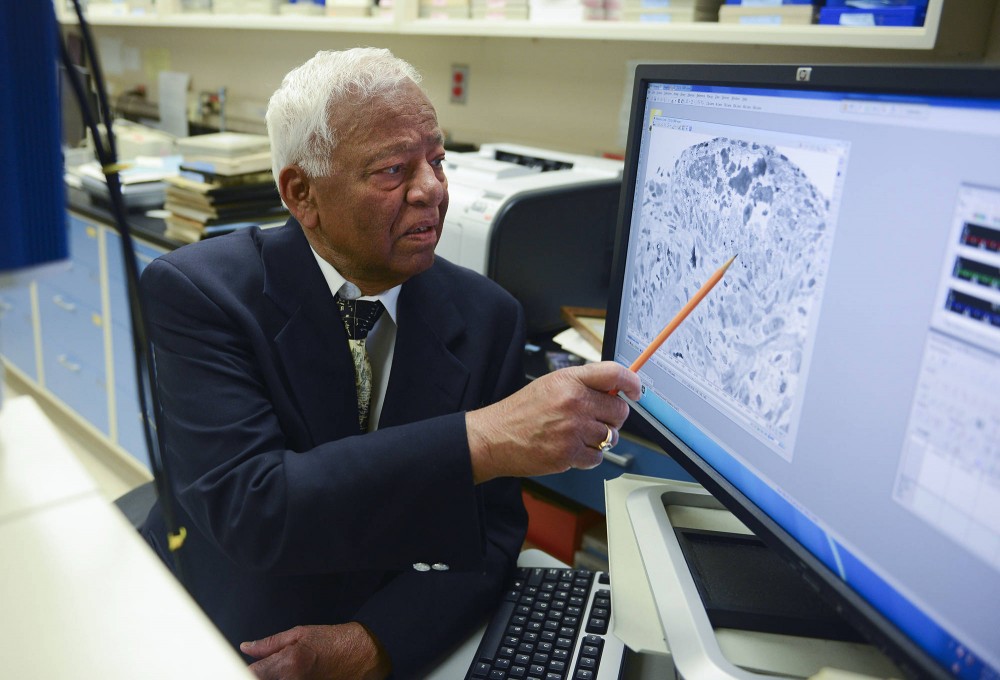

For more than three decades, Sinha, now 81, has been a research pioneer in his studies of both Antarctica and cancer.

“I think I’ve made a mark in both fields,” Sinha said.

Though Sinha’s National Science Foundation-funded research in 1972 focused on the population of seals, whales and birds on Antarctic pack ice, he took on cancer research at about the same time, an endeavor he’s still pursuing.

He remains just as passionate about Antarctic resources today as he is about searching for a cancer cure.

One of his studies, published last summer, discovered that some patients’ immune systems were more effective than others in killing cancer that has spread from its origin into lymph notes. That research could help predict the survival of patients with metastatic cancer in their lymph nodes.

Between researching and lecturing, Sinha has also made time for his own personal research. He said he spent five years tracing his family history back to 1739, when an attack on Delhi prompted his family to settle in a village called Churamanpur in India.

Michael Wilson, a lab medicine and pathology professor at the University and longtime colleague of Sinha, said Sinha’s curiosity and impact spans across subjects.

“He’s an intellectually stimulating person,” Wilson said.

“[He’s] very inquisitive; he likes to ask questions.”

Sinha, who began working at the University in 1967 and taught cell biology and zoology there for more than 25 years, said he misses learning from his students as much as he misses instructing them.

“Teachers learn from students as much as they learn from teachers,” Sinha said.

“They may ask an innocent question that triggers a thought process that could’ve never been triggered.”

Sheila, Sinha’s daughter, said her father played the role of teacher at home, too, pushing her to broaden her mind by trekking the world and advising her to read books three or four times.

“Education was the No. 1 thing on his list for me,” Sheila Sinha said. “[But] it wasn’t that you had to get an A.”

Antarctic exploration, lab discoveries

In 1972, and again in 1974, Sinha and a team of researchers spent about three months surveying and studying the health of seals, whales and birds in the Antarctic seas of Bellingshausen and Amundsen.

That research helped establish critical baseline data for future research, climate change debates and United Nations population conservation efforts.

Between excursions, Sinha said the 200-person crew aboard their U.S. Coast Guard ship would avidly play poker, rummy and eventually bridge, once Sinha taught the entire ship how to play.

At 81, Sinha isn’t the same vigorous young researcher who set off to the Earth’s southernmost point in the name of science, visiting countries like Argentina and New Zealand on the way.

But Sinha said that doesn’t mean he’s done being a pioneer, particularly in the field of prostate cancer research, the second-most common cancer in American men.

Currently, Sinha is investigating which cells are killed during cancer treatments like chemotherapy. This fall, he will present a currently unpublished paper at an international cancer research conference in Greece.

Sinha said he has published more than 110 research papers, many of which were efforts not funded by grants. For some, he hired student researchers out-of-pocket to assist him in his research, he said.

And though he officially retired from the VA Center more than 15 years ago, he never stopped doing research there five days a week voluntarily.

“I didn’t receive any grants. I didn’t receive a nickel from this,” Sinha said. “I said, ‘I will do what is right — if you don’t give me money, that’s OK.’”

Sinha’s wife, Dorothy, whom he met at a party in Dinkytown more than three decades ago, said he shows no sign of stopping anytime soon — regardless of whether he’s receiving a salary or grant money.

“He just loves what he does and he says he’s never going to retire,” she said.

“We got married and he said, ‘I’m going to be slowing down before you are,’” Dorothy Sinha said. “I keep saying he’s breaching his premarital agreement because he’s not slowing down at all.”