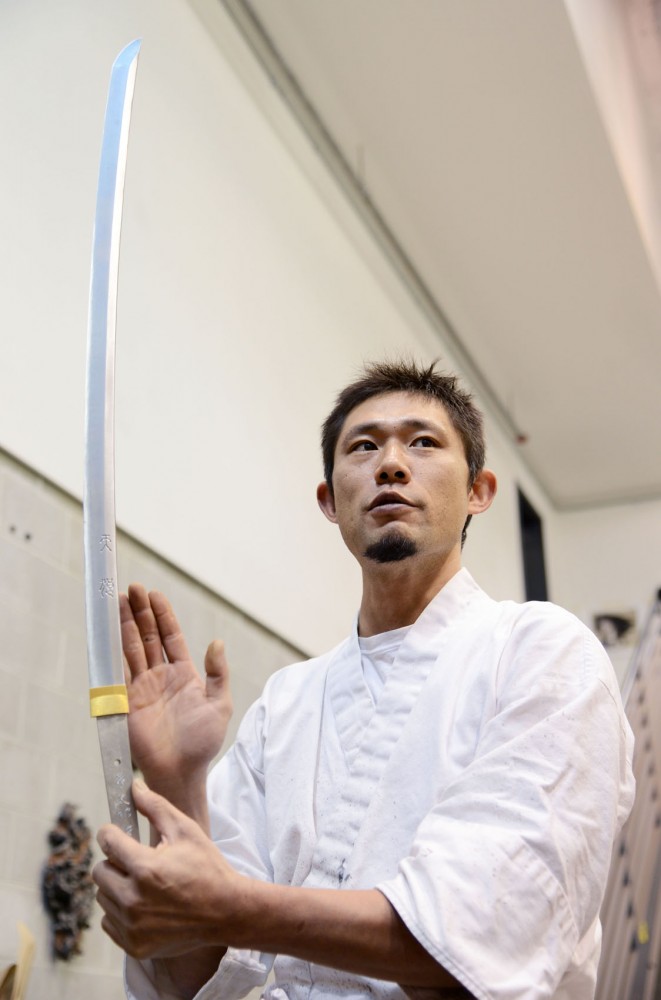

Taro Asano spent six years as an unpaid apprentice before his master, Fujiwara Kanefusa, told him he was ready to be licensed as a master swordsmith.

To be officially licensed in Japan, swordsmiths have to pass a test given by Japan’s Agency for Cultural Affairs, which strives to preserve various Japanese arts. Today, Asano’s swords retail for $20,000 and up.

Asano, otherwise known by his professional name, Fusataro, is a 25th generation swordsmith and one of about 200 licensed swordsmiths living in Japan.

“I wouldn’t call it a dying art, but it’s definitely not flourishing,” said Allen Rozon, Fusataro’s friend and traveling companion.

On Wednesday, Fusataro will be smelting Minnesota magnetite in a traditional clay tatara, or Japanese oven, made by University of Minnesota Professor Wayne Potratz at the Regis Center for Art to promote the art of sword-making. Fusataro is the first-ever Japanese swordsmith to visit the University.

Myths about smiths

Swordsmithing traditions across the globe differ not only in process and functionality, but in the mythology that surrounds them.

In some parts of Africa, blacksmiths are ostracized from their communities.

“There’s this whole spiritual and dangerous aspect around it because they take materials from the earth and turn them into this hard object,” said Richard Furrer, owner of Door Country Forgeworks.

For the same reason, sword-making was delegated to elves in medieval mythology.

“They had to make [swordsmiths] into mythical beasts because they made the weapons for the gods,” Furrer said. “Items that powerful can’t possibly be made by man.”

The primary difference between Japanese and European swordsmithing is that the Japanese tradition has remained virtually unbroken through the centuries, whereas the European tradition was lost with the rise of modern warfare.

This break has presented smiths who focus on medieval swords with challenges in gathering information and maintaining accuracy.

“In Japan, they choose to be caretakers of this ancient craft,” Furrer said. “That’s why people still like Japanese sword-making — the mythology still exists.”

Maintaining tradition in modern times

We now know that blacksmithing isn’t a form of magic, but a result of physical and chemical processes.

The same scientific advancements that removed the mythical element of sword-making led to increasing opportunities for mass production.

Modern commercial sword makers looking to imitate Japanese and medieval blades have learned to make cheap replicas using sheet metal and mechanized processes.

To an extent, it’s been necessary to modernize in order to make a living by swordsmithing. The Minneapolis-based company Arms & Armor had adapted some of these practices, including cutting blades from modern steel sheets, while adhering to tradition as much as possible.

“We’re not trying to invent something that’s better than anything that’s ever come before,” said Craig Johnson, the production manager at Arms & Armor. “For us today to think we can out-design that tradition is kind of an arrogant thing.”

Arms & Armor has an extensive library that smiths refer to when researching the swords they wish to recreate. Additionally, smiths are generous when it comes to sharing techniques.

To ensure their swords stay true to the originals both in appearance and function, Johnson and other Arms & Armor employees create training swords that they test out themselves.

Fusataro ensures quality by producing numerous blades for every order he receives.

“If I want to make a good katana, I need to make lots of practice katanas,” he said.

The Japanese government allows licensed swordsmiths to make 24 swords per year, but Fusataro only makes about 10. Each blade takes him at least a month to create.

And the process doesn’t stop there. Japanese swordsmithing typically involves up to five craftsmen who specialize in various areas like polishing, scabbard-making and guard-making.

“Think of [Asano] or the swordsmith as a contractor building a house,” Rozon said. ”Basically the job comes to Taro. Taro forges the sword and then hires the other specific craftsmen to make the other parts.”

The current state of smithing

The modern sword market consists of three types of people: martial artists with money, collectors who want to buy swords from dead people and people who want to commission swords from today’s masters, Rozon said.

The competition for swordsmiths like Taro and Furrer is companies cutting blades from cheap sheet metal and selling them at low costs.

But master swordsmiths don’t settle for less. Fusataro still performs the traditional smelting process of adding iron sand to the tatara, which is heated by a charcoal fire. From the tatara come chunks of steel called tamahagane that are then folded repeatedly to remove impurities and then forged into a blade.

This process and ones like it are what first attracted Furrer to swordsmithing.

“If I told you what man went through to develop the steel technology that we have today, you wouldn’t believe it,” he said. “That pursuit pushed science further down the road than any other interaction.”

Furrer said he doesn’t even particularly like swords.

“The finished product does very little for me –– it’s the process to make it,” he said. “We’re never as creative as when we make things that kill other people.”

What: Tatara firing with Fusataro and Wayne Potratz

When: 8 a.m. to 8 p.m., Wednesday

Where: Sculpture Courtyard for the Regis Center for Art

Cost: Free

What: Presentation by Fusataro

When: 7 p.m., Thursday

Where: InFlux Space at the Regis Center for Art

Cost: Free