Known to be somewhat cantankerous, Ernest Hemingway would be incredibly satisfied with the collective dislike millions of students share for his work. At one point or another, upon finding ourselves hopelessly lost in a labyrinth of Shakespeare or Hawthorne, each of us has searched for loopholes, either by CliffsNotes or fever dreams of dropping out. Hemingway, Harper Lee and Faulkner cheerfully stood in the way of our high school diplomas, but even in college, we haven’t escaped them.

Whether students admit it or not, English classes offer more substantial skills than the ability to navigate Old English prose; the subject matter has less to do with literature, and more to do with living. However, the vast majority of the works we semi-voluntarily consume were published decades ago. While their literary merit may withstand the course of time, some novels have aged better than others.

The intractable flaw older classic novels carry, which are standardized in schools and universities across the country, is thematically evident. Even the greatest works of fiction, the ones that capture the essence of the human experience and tragedy, often disguise subliminal elements of homophobia, racism and sexism. In recent years, a public school in Duluth removed both To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee and Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain from their standard curriculum, noting that their use of racial slurs made students uncomfortable. The list of questionable reading does not end there. Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell is an incomparably beautiful work of historic and romantic literature, but reads like a neo-confederate fan fiction. Even The Awakening by Kate Chopin, which was once celebrated as a feminist laureate, is criticized by today’s activists for failing to represent women outside of the white upper class.

As a population of academics, we could opt to move away from historically flawed literature — certainly books without questionable biases exist. There might even be an argument that our failure to move forward is a reflection of laziness. However, others point out that recognizing these fallacies is essential for community growth. Professor of English, Sybil Durand, at Arizona State University writes, “When we choose to abandon books that deal with issues of race, sex, abuse, gender identity, discrimination, disenfranchisement, or similar topics, we hurt the people who live with these issues every day by implying that their life experiences are not worth talking about, or are an embarrassment.”

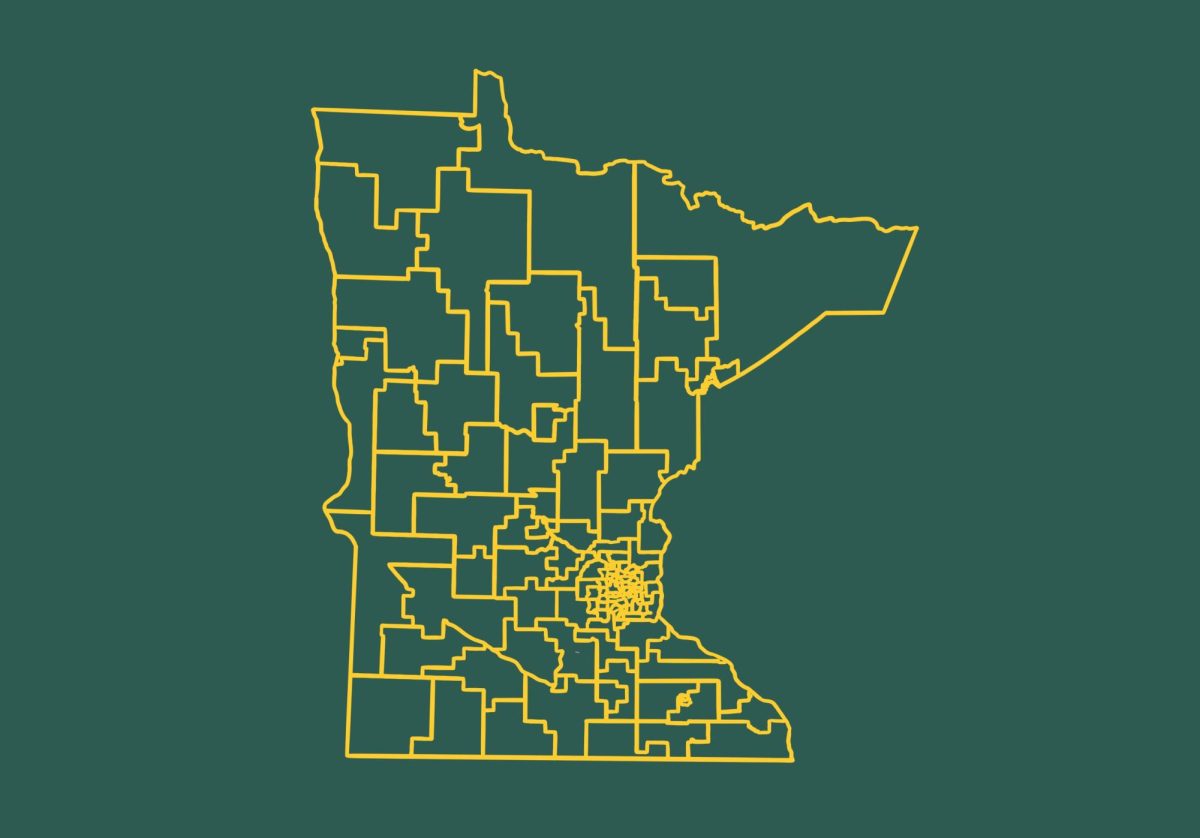

The dichotomy of censorship and social progress stipulates a challenging debate about which texts are classroom-appropriate. At the University of Minnesota, students are only required to take three credits of literature, or approximately a single, one-semester English class. This means that professors have a very limited window to make an impact on their students. Old books are minefields of political incorrectness, sometimes causing classroom chaos, and requiring in-depth analysis beyond the comfortable restrictions of artistry and plot. So, why take the chance on a 50-year-old, potentially problematic book?

Every year, good educators accept the challenge, because frankly, there might not be a better American novelist than John Steinbeck, even though a significant portion of his writing is blatantly sexist. Dated literature is an uncomfortable reminder of distasteful history, but in another sense, it is also an uncomfortable reminder of modern issues. Although we prefer to reference certain social issues as figments of the past, they are seldom truly historical. Contemporary authors and publishers don’t usually release materials which are blatantly politically incorrect, but the issues still exist in a cultural sense. Old novels which display the discriminatory nature of humanity demand a level of critical thought and societal awareness which can’t be achieved elsewhere. Injustice is not a figment of the past, and comfort is scarcely a mechanism for change.