Growing up in a small Dakota community in southwest Minnesota and attending public school, Vanessa Goodthunder never saw a Native American teacher leading her classes.

Goodthunder, a teacher candidate at the University of Minnesota, said she never saw a strictly Native American curriculum taught, either; when it was, it was in a generalized and stereotypical fashion.

The experience pushed her to go into teaching.

“My goal was to become a teacher and change that for other students and change the curriculum,” Goodthunder said.

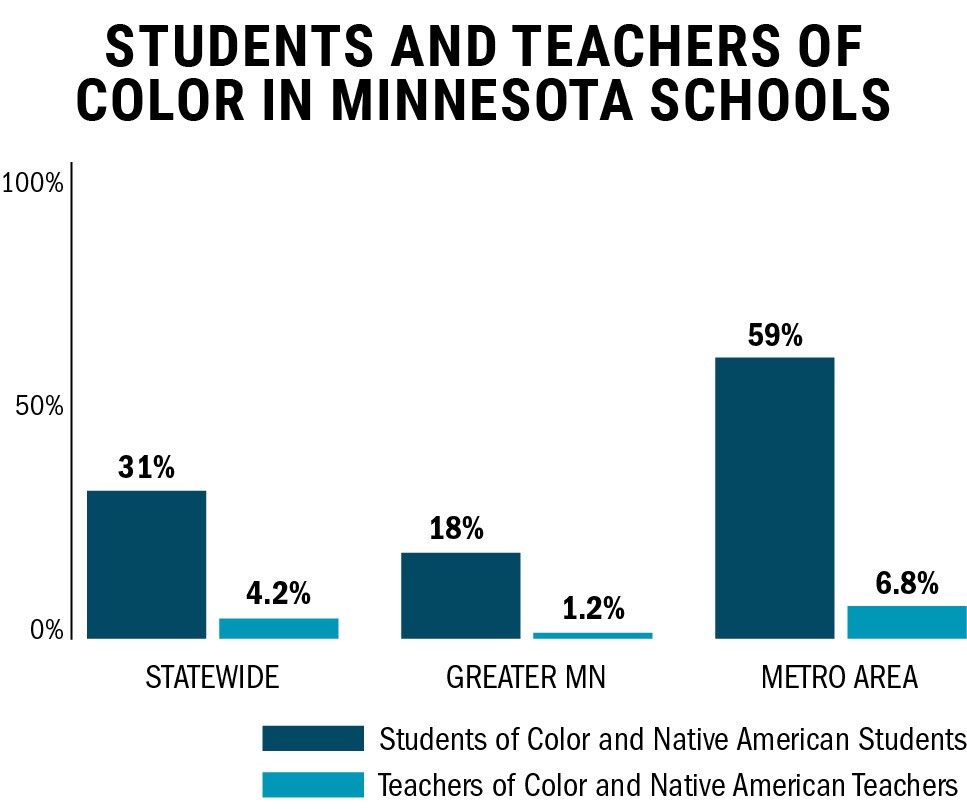

In Minnesota, where 4 percent of the state’s teacher workforce are teachers of color, a group, called the Coalition to Increase Teachers of Color and American Indian Teachers in Minnesota and University professors and graduate students are looking for ways to increase teacher diversity in Minnesota schools.

The group of educators and experts from Minnesota schools and universities as well as several organizations from across the state hope to enhance diversity among teachers, said Vichet Chhuon, an associate professor in the College of Education and Human Development.

The group is pushing for the Minnesota Legislature to provide more opportunities, like increased scholarships and teaching stipends, for teachers and teacher candidates to increase diversity in schools.

The coalition wants to increase the percentage of Minnesota teachers of color and Native American teachers to 8 percent, which would require nearly 750 more nonwhite teacher candidates a year for the next three years.

Sasanehsaeh Pyawasay, a graduate student at the University, said it’s important to make sure that teaching programs recruit a diverse body of students.

Goodthunder said she is the only Native American student in her program.

Pyawasay said schools need to examine how teaching programs are advertised to populations of color and consider how to make sure the programs are culturally competent.

Chhuon and Mistilina Sato, an associate professor in CEHD, said there are several other factors that play into the racial disparities among teachers.

Standardized testing requirements for teaching licenses are unnecessary in many cases, Chhuon said. They often don’t cover what teachers of color bring to the table, and there can be alternative requirements for license, he said.

Chhuon said additional requirements, like experience, can also be barriers for teacher candidates of color, who may be economically disadvantaged. The solution lies in balancing requirements and changing them to allow more freedom for the individual.

Additionally, teaching programs are expensive and required teaching experience usually takes almost a year, which becomes difficult to balance with a full-time job or family, Chhuon and Sato said.

Further, teaching is viewed as a less-prestigious profession in the U.S., which doesn’t attract many candidates to begin with, much less candidates of color, Sato said.

It’s also important to recognize that diversifying ideas and perspectives is better, Sato said. Schools need diverse people where varying perspectives can be shared. Otherwise, schools become dominated by a single perspective.

Chhuon said the coalition is cultivating a partnership with the University’s Race, Indigeneity, Gender and Sexuality Studies initiative.

Pyawasay said it helps students of color to see teachers of color leading a classroom. “It’s helpful for students to see folks like them teaching classes; it brings a different perspective.”

It’s good for students of color to be taught by someone who can relate to their experiences, Goodthunder said.

“Education can look like we want it to, and we can change it together and make it look different,” said Goodthunder.