What: Discussion of Nuruddin Farah’s “Crossbones”

When: 7p.m., Oct. 29

Where: The Loft Literary Center, 1011 S. Washington Ave., Minneapolis

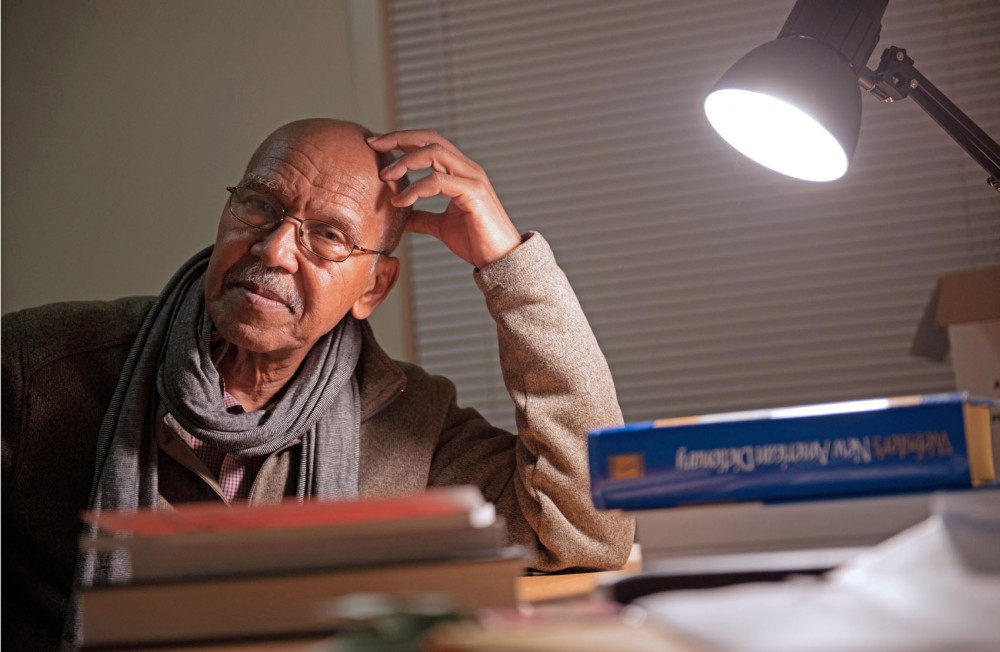

Distance and time usually separate Nuruddin Farah from Somalia, but this never prevents him from imagining his native country in his fiction.

The novelist, heralded as one of Africa’s most important writers, seems to capture his home country with ease. From the British colonial rule of the 1930s to the ongoing civil war beginning in 1991, Farah’s breadth of knowledge and memory informs his writing.

“The only problem I have is that there is a shortage of time,” Farah said. “Anytime I have a bit of time, I can write about the past, about the present, about the future.”

As the Winton Chair in the College of Liberal Arts, Farah teaches International Fiction at the University of Minnesota. Farah commutes between his homes in Cape Town to Minneapolis often yet envisions Mogadishu in his writing life. Somalia’s capital is often the major setting of his eleven novels including the latest “Crossbones,” as well as the upcoming staged reading, “A Stone Thrown at the Guilty.”

The perennial Nobel Prize nominee for fiction told PBS’ NewsHour” his enormous mission as young man, “to keep my country alive by writing about it.” Farah still expresses optimism for his country’s future after his latest return to Somalia in May.

“It was the first time in 21 years that I could move about without having armed escort,” Farah said. “I’m hopeful that if that continues — if peace becomes fashionable, if everyone buys into it — then we can get somewhere.”

As the final story in his latest trilogy, “Past Imperfect,” “Crossbones” weaves the stories of a return to the war-ravaged state following the military dictator and former President Siad Barre’s departure. Farah’s immediacy echoes a thriller — yet the plot reflects a bitter reality in Somalia’s current events.

“Because this is happening and the things that ‘Crossbones’ is about are the things that have just happened or are likely to happen now, I have to take it very seriously,” Farah said. “The tone has to be an urgent tone.”

“Crossbones” finds Jeebleh and his son-in-law Malik experiencing an eerie calm in Mogadishu. Simultaneously, Malik’s brother Ahl searches for his stepson Taxliil in Puntland. Recruited by an imam, Taxliil disappeared from Minneapolis to aid in the area’s rising religious insurgency. Al Shabab’s increased military presence in “Crossbones” mirrors Somalia’s recent history — a power Farah sees as waning with suicide attacks representing total desperation.

“I think people have to remember that that attitude usually smacks of desperation,” Farah said. “Because it’s one thing for you to have the power in a town and to dictate how it’s going to happen, it’s another one to come in like a thief in the night.”

To combat the desperation, Farah writes critical fiction like his 1976 work, “A Naked Needle.” After the Somali government learned about the writer’s penchant for subversive literature, Farah embarked on a self-imposed exile from Somalia that lasted until 1996. Although elaborate plots riddle Farah’s tense fiction, the author describes Somalia’s future in very plainspoken terms — often missing from current discourse about the country, he explained.

“Somalis are misunderstood because there are not many people who can explain what has made a very complex situation,” Farah said. “Somalia is no more complex than America.”

With the first elected government since 1991, Farah remains hopeful of Somalia’s future. But in the meantime, the author will continue to dream of his permanent return to the country.

“If and when Somalia becomes cosmopolitan again,” Farah said, “when the city of Mogadishu regathers itself and becomes a livable, lovable city, I will be prepared to go back and live there.”