A new epilepsy ‘rescue’ medication developed by University of Minnesota researchers will make receiving treatment more accessible for patients who suffer from seizures.

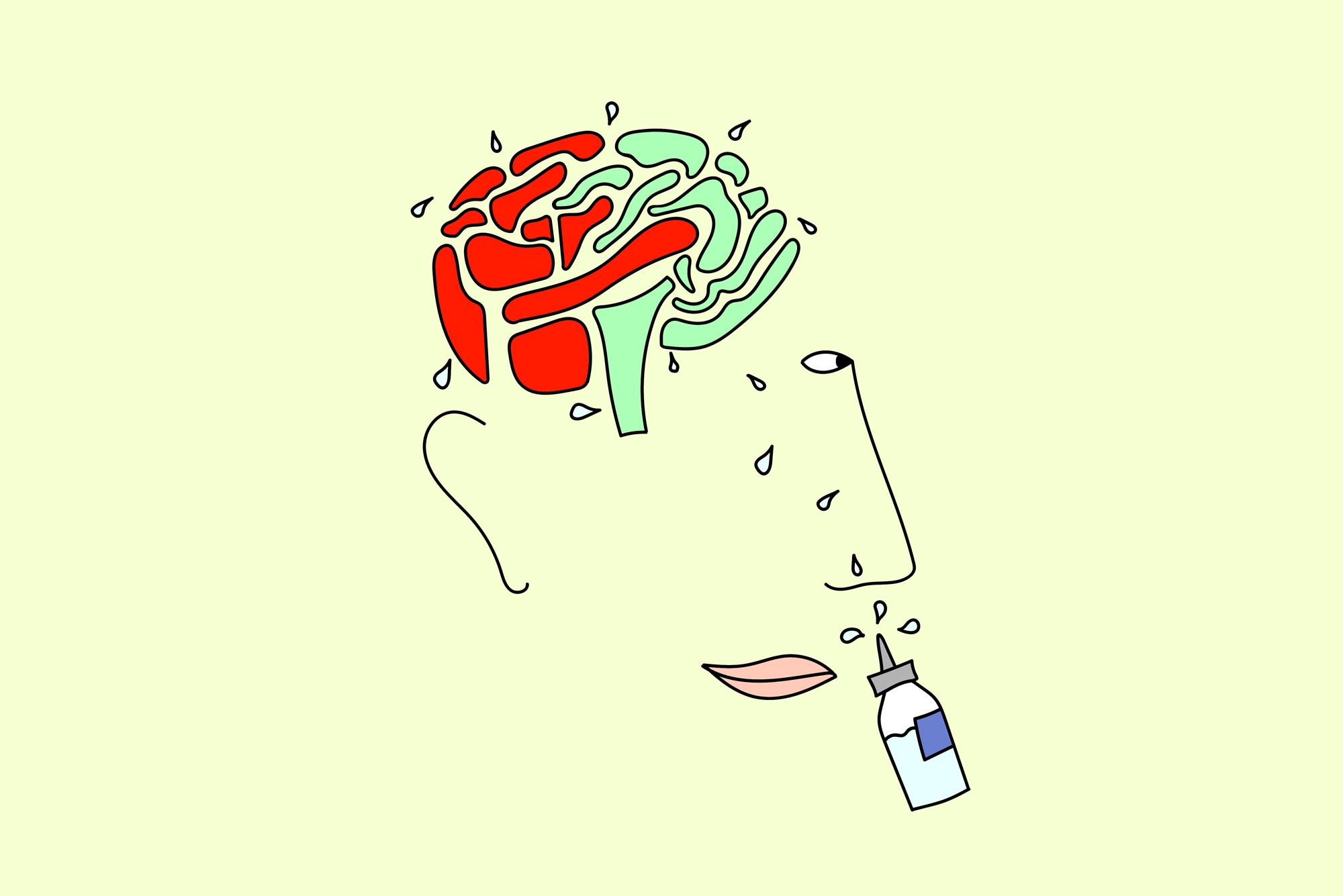

The first of its kind medication is administered through a nasal spray by the patient or caretaker. The medication is able to stop seizures as they happen and aims to reduce the frequency and cost of medical visits for epileptic patients. Previous treatments required the use of an internal or injectable product that had to be administered in a medical setting and by a medical professional.

“[This development] is enormously important. If people have a crisis that requires a trip to the emergency room, it is exhausting and life is out of control for that time,” said Robert Kriel, a professor in the University’s Department of Experimental and Clinical Pharmacology. “Having a product that is more feasible is another big step forward, because it enables families and patients to control their lives.”

The medication, called VALTOCO, received approval from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration after more than a decade of clinical trials and studies. The product will be available to the market in the coming weeks, said Craig Chambliss, the co-founder and CEO of the neuroscience and pharmaceutical company Neurelis that collaborated with the University to develop the drug.

“We were presented with this idea in 2002 and have been working on trying to figure out how to pull together a treatment. I talked with Dr. James Cloyd about a proof of concept study in 2010. Four more studies were requested by the FDA, and we treated over 4,000 seizures, more than in the history of epilepsy,” Chambliss said.

In addition to being a more accessible and cost-effective treatment, the rescue therapy is capable of preventing clusters of seizures, said James Cloyd, a University professor and director of the Center for Orphan Drug Research at the College of Pharmacy.

“[VALTOCO] can actually prevent the next seizure. When a patient, family member or doctor can recognize when a cluster [of seizures] is going to occur … the drug can be administered to stop the next seizure,” Cloyd said.

Treatments with the capacity to be administered outside of the home are critical to stopping seizure emergencies and hospitalizations, said Claire Colliander, interim executive director of the Epilepsy Foundation of Minnesota, in an email to the Minnesota Daily.

“Expanding safe treatment options and delivery methods is a positive outcome for people with epilepsy,” Colliander said in the email. “We always encourage individuals to work closely with their doctors to find the best treatment for them. We are grateful for the work of the U of MN researchers who are working to improve the lives of people with epilepsy.”