University of Minnesota athletics spending has favored men over women in areas that show a lack of dedication to Title IX, the federal law that prohibits gender discrimination in education.

But few eyes are watching to catch issues like those at the University, where men’s sports get almost three times the financial support as women’s. Those who do feel there is a problem are often afraid to speak up.

The school made plans to improve in 2008, when a University subcommittee raised gender equity concerns, but the problems have gone largely unresolved.

Outside oversight has decreased recently because the NCAA put a moratorium on school self-reviews in 2011. That has left the University largely on its own to police athletics department spending.

“No, I don’t think we’re out of compliance,” athletics director Norwood Teague said. “But it’s an ongoing job to stay in — you can easily get out of compliance if you’re not careful.”

The University reported spending significantly more on men’s sports in the past two fiscal years.

And the trend is set to continue this year. In the first half of the current fiscal year, athletics spent $21.89 million on men’s sports but less than $9.96 million on women’s, according to a Minnesota Daily review of spending data.

The review uncovered several indications that the department goes against the spirit of Title IX:

•The department spent 125 percent more on men’s recruiting than on women’s last year.

•It spent 24 percent more on men’s scholarships than on women’s last year.

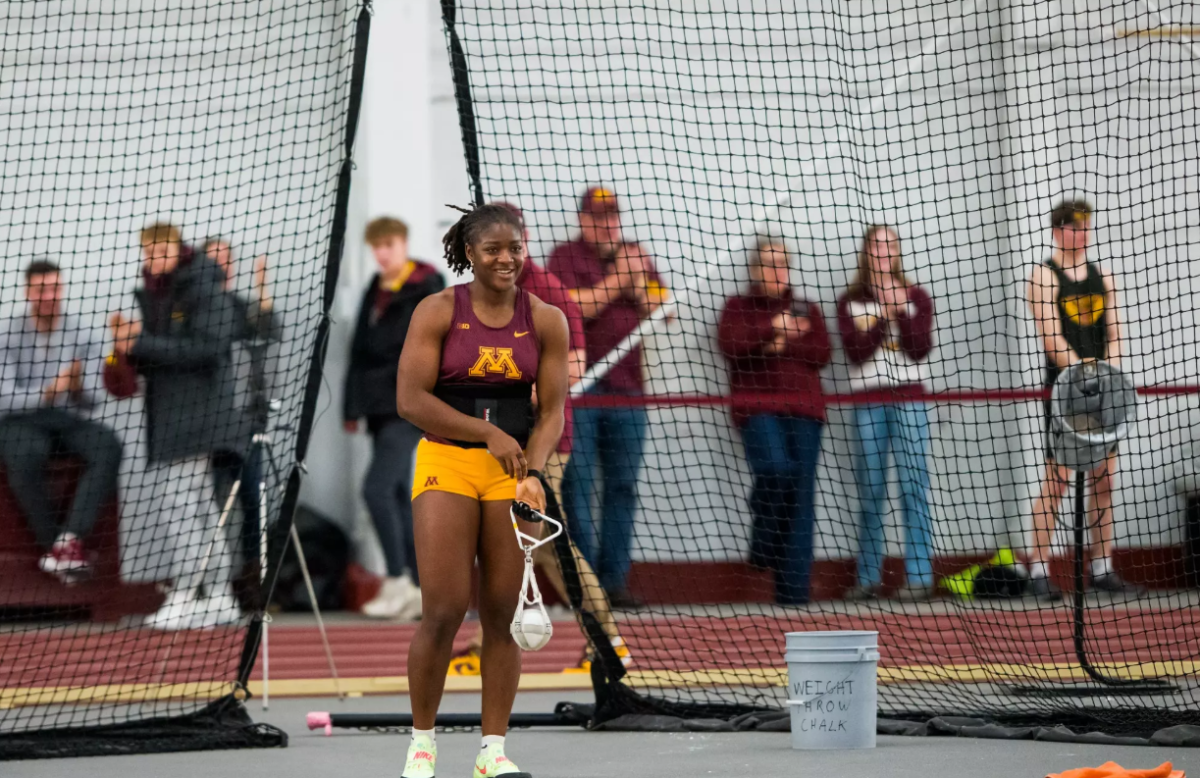

•Large women’s rosters in track & field and cross country help the University balance participation rates between men and women. But they misrepresent the number of participants by counting them three times — once for the cross country season and twice for the indoor and outdoor track seasons.

•Because some women’s rosters are much larger than needed for competition, many athletes don’t compete at the conference level, which some say waters down the collegiate athletic experience.

•The department spent about two-thirds more on men’s recruitment travel than it did women’s from July to December 2012.

To some in the college athletics community, these gaps suggest the University is not committed to gender equity.

Title IX compliance was an issue at Virginia Commonwealth University, where Teague was athletics director before he came to Minnesota.

Teague’s background, coupled with the athletics department’s current struggles with gender equity, has some donors cautious about maintaining their support.

“Let’s not beat around the bush; let’s not come up with fancy reasons — this is gender discrimination,” said Nancy Hogshead-Makar, a law professor in Florida and the senior director of advocacy for the Women’s Sports Foundation.

Pushing the boundaries

Despite eight sections and nearly 2,000 words, Title IX has plenty of gray area.

“There is no rule or number of disparities that when reached constitutes a violation,” according to a 1990 Office for Civil Rights Title IX investigation guide.

“If a pattern of discrimination is evident, if it appears that athletics of one sex are accorded ‘second class’ status, then a violation is likely.”

The OCR considers 13 areas within an athletics department to determine its compliance.

Since 2010, the University’s spending patterns and reported budgets in at least three of those areas — scholarships, equipment and recruiting — have favored men’s sports.

The University’s Office of the General Counsel declined to comment for this story.

The University spends about the same percentage of its budget on men’s scholarships and recruiting as its Big Ten peers, according to Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act reports.

In OCR’s analysis, it considers each of the 13 areas and assesses whether gender imbalances have a “disparate impact on one sex.”

Scholarship spending and participation rates are the only two of the 13 areas that are quantitative, former University women’s athletics director Chris Voelz said. The OCR checks whether student-athlete proportion matches the school’s undergraduate population in gender representation. The University’s athletics department does.

The OCR also checks whether scholarship allocation is “substantially equal” to the male-female ratio of athletes.

The University spent 24 percent more on men’s scholarships than on women’s last year, a difference of more than $800,000.

Beth Goetz, the new senior women’s administrator for the University’s athletics department, said the department provides the maximum number of scholarships allowed by the NCAA to both men and women given its current sport distribution.

The NCAA sets a cap for each sport on the number of full scholarships or, in other cases, a maximum on total scholarship dollars to be divided among student-athletes on a team.

But those limits sometimes set schools up to fall short in their OCR scholarship evaluation.

“Unfortunately, the NCAA equivalency limits set you up to often times, obviously, be out of compliance,” Goetz said. “So everybody struggles with that piece a little bit.”

A school could, however, reorganize its department to offer more sports or a different blend of sports to allow for more scholarships to women.

“[The University] cannot use either an ‘I cannot afford it’ excuse or an ‘NCAA rule prevents me from complying’ [excuse],” said Donna Lopiano, a women’s sports advocate and former women’s athletics director at the University of Texas.

Athletics departments are not required to spend equally on male and female student-athletes across the board, Lopiano said. Many of the 13 areas the OCR considers in its investigations are qualitative.

Some experts say certain types of spending discrepancies are fair. Replacing top-of-the-line football equipment each year will cost much more than doing the same for volleyball, but the OCR checks that volleyball players get the same caliber of high-quality equipment.

Even so, the magnitude of some spending differences has some questioning the athletics department’s commitment to gender equity.

• In six of eight comparable programs, the men’s team spent significantly more than its women’s counterpart on recruitment travel from July to December 2012.

• Men’s teams accounted for about two-thirds of the department’s equipment and recruiting spending last year.

• Men’s basketball spent 46 percent more on recruiting than women’s basketball and more than twice as much on equipment.

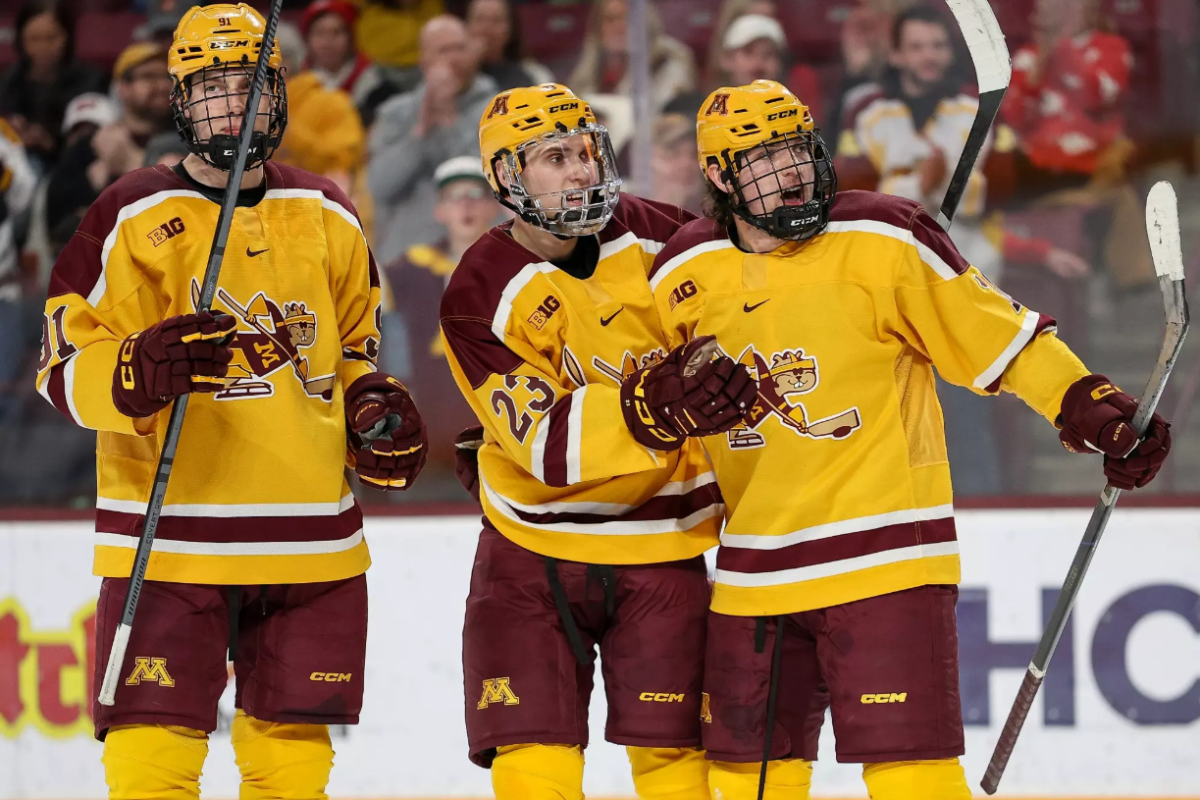

• Men’s hockey spent more than twice as much on recruiting as the women’s hockey team and almost twice as much on equipment.

Goetz said in an email that disparities can be explained in part because of market differences. She said men’s hockey sticks, for example, break at “a significantly higher rate than women’s,” resulting in increased costs. Furthermore, top-of-the-line men’s basketball uniforms from Nike cost about twice as much as those for women, she said.

NCAA rules allow for 210 recruiting days for football, 130 days for men’s basketball and 100 days for women’s basketball. So by supporting coaches as much as possible, the University will likely incur greater expenditures on the men’s side, Goetz said.

While NCAA regulations and costs can affect some budget components, “it’s a red flag when it’s that far apart,” said Hogshead-Makar, of the Women’s Sports Foundation.

The department manipulates participation numbers by double- or triple-counting multi-sport athletes — notably track & field runners who compete in the indoor and outdoor seasons and run cross country. The University double- or triple-counts many more women than men because women’s track & field and cross country rosters are much larger. As a result, the athletics department appears in NCAA reports to have a higher percentage of women than it does.

Some former athletics directors from the University and other schools said the large roster sizes of women’s track & field and cross country water down the athletic experience because of high athlete-to-coach ratios and less access to competition.

“I’m not sure they get the quality of experience that they wish,” former University women’s athletics director Voelz said.

The University reported 524 female and 469 male student-athletes in fiscal year 2012, according to the most recent Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act forms. But when multi-sport athletes are counted only once, there are 398 women and 414 men.

Some former athletics directors, like Lopiano, say three separate seasons and three NCAA championship meets allow more scholarship money for female athletes.

Others say that because the three sports are so closely related and the rosters are so similar, counting one athlete as three is misleading. Nearly every cross country runner is reported as three participants, because the athletes also compete in both indoor and outdoor track.

“That to me is an outrage,” former University women’s athletics director Merrily Baker said when shown roster sizes at the University. “It appears they’re playing a numbers game there. They’re not running a sports program that’s equitable.”

Part of the concern with large rosters is having athletes who never compete at the conference level. Hogshead-Makar said she’s wary of schools having “varsity and JV” rosters. In some cases at the University, a team’s top athletes will compete with Division I competition while less-talented athletes compete with local Division II or Division III schools.

“What this practice does is it keeps the school from having to add new teams for which there would be real competition and real availability,” Hogshead-Makar said.

Donors wary

Skirting the spirit of the law may be financially beneficial, as it allows the University to spend more on the only three sports that make it money: football, men’s basketball and men’s hockey. Success in those sports raises the profile of the athletics department, which can lead to more booster contributions.

But the athletics department also receives money from a strong contingent of donors who are fervent women’s athletics boosters. With millions of dollars in contributions, they’ve helped fund new facilities for women’s teams on campus. That crowd is wary of Teague as it attempts to gauge his priorities for the department.

Some are in wait-and-see mode, and several have even stopped giving money because of concerns that gender equity has become less of a priority, said multiple donors that stay in touch with the group.

“It’s a stewardship issue with money,” said Deborah Olson, who donated $900,000 to build the University’s soccer stadium in the late 1990s. “There are a lot of people who are absolutely not giving until they get a sense that things will be OK and that the athletic department will do right by all the student-athletes.”

Olson and others said they will continue to give but will evaluate the department again at the end of Teague’s first full year.

Goetz said it’s too soon to examine the current staff because budgets through this year were former athletics director Joel Maturi’s responsibility.

Many donors said they went through the same anxieties when Maturi took over in 2002 and oversaw the merging of the formerly separate men’s and women’s departments.

“When the University forced that [merger] in the not-too-distant past, promises were made that gender equity would not be an issue under the merged department,” Baker said. “It would be all taken care of, and guess what, it’s not.”

Olson pointed to Teague’s history at VCU as a factor in her assessment of his first-year performance. There, women’s underrepresentation in the athletics department prompted it to bring in an outside Title IX consultant.

Teague frequently deferred to Goetz or spoke vaguely of his program goals when asked specific questions about the department’s spending and gender equity concerns raised in this story. In several cases, he and Goetz acknowledged they plan to look closer at the department’s compliance.

“I think things are being done a lot differently [from Maturi’s era],” Olson said. “Whether it ends up being a significant shift in commitment away from women’s student-athletes I think is something that needs to be looked at.”

Olson said she’s willing to wait until the end of Teague’s first year to see his spending pattern.

No teeth

Problems like disproportionate spending can persist because schools have little oversight.

The NCAA has no jurisdiction in Title IX compliance because it’s a federal law, Baker said, but it does have its own gender equity rules.

If the OCR finds a school to be out of compliance, the school can be stripped of its federal funding. But that’s never happened.

Lopiano said in her experience, the OCR will more likely strike a deal with the school and give it a plan to help put it back in compliance.

The NCAA used to require its Division I members to review their own athletics programs, including their Title IX compliance, every 10 years. But in 2011, the organization put a moratorium on self-reviews in an attempt to cut costs and reduce the burden of the lengthy process. Goetz said the NCAA will phase in a new approach that requires filing every year but with a less comprehensive report.

The subcommittee in charge of the University’s 2008 review has raised some gender equity concerns with Teague. These include travel spending and participation rates, said Kim Hewitt, the University’s Title IX officer. But the school hasn’t faced any penalties.

The subcommittee has also requested that the athletics department add a step in its budgeting process to formally consider gender equity, Hewitt said.

Goetz said it’s good that Hewitt is not involved in budgeting because she can be more objective as an outsider.

But Baker criticized not including people in positions like Hewitt’s in the athletics department.

“I don’t get that at all,” Baker said. “That’s another layer of bureaucracy. I think a Title IX specialist has to be in the athletics department, working with them day after day after day after day with a focused look at compliance issues and not just complaints.”

Culture of fear

Some national experts say gender discrimination persists in part because of intimidation within athletics departments.

“Nobody’s willing to say what’s true,” Hogshead-Makar said. “People feel that if they speak out on behalf of a very popular federal law,” they could lose their job.

Sources with knowledge of the University’s athletics department describe a culture of fear in which people watch their words carefully.

“I think everyone’s walking around on eggshells. They’re afraid,” said Chris Howell, an administrative assistant who’s been with the University’s athletics department for 25 years. “Is that a good work environment? Is it a healthy work environment? Well, it’s not one that people would choose to be in.”

Both former women’s athletics director Baker and Hogshead-Makar said the culture of fear pervades athletics departments across the country.

Baker said the department has an ethical standard to uphold that trumps the importance of even the federal law.

“Title IX is a legal mandate; gender equity is a moral imperative,” Baker said. “Minnesota is not in line with the last part of that.”