Sean O’Mara walks the St. Paul campus to get a break from writing his dissertation. The campus is beautiful, he said, but he can’t escape the guilt of not being in the lab.

“A month or two ago, I would be in lab for six hours and writing for two to three hours, and I’d get a full day in,” he said. “Now it’s like I write for four hours a day and I’m kind of like twiddling my thumbs the whole time.”

The end of the government shutdown couldn’t have come soon enough for O’Mara. Like other graduate students, the shutdown forced him out of his lab and stalled his research. Now, he and others have to make up for lost time and hope it doesn’t happen all over again in three weeks.

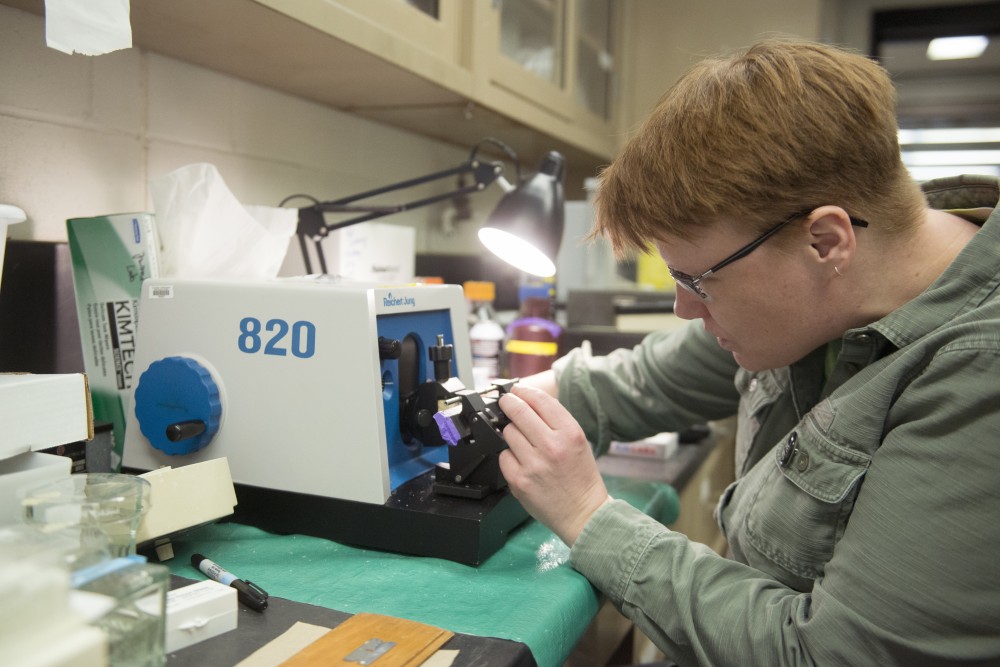

Six graduate students were kicked out of the Department of Agriculture-owned Cereal Disease Lab when it closed after the agency ran out of funding on Dec. 22. O’Mara was one of them. He’s a Ph.D. candidate who researches fungal pathogens deadly to wheat and toxic to humans. An escaped mutant strain could be catastrophic, so the lab has strict quarantine rules.

With his fungal cultures “just chilling” in a minus-80-degree-Celsius freezer, O’Mara said his research has been stagnant. He can’t collect the results he needs to complete sections of his dissertation.

“So now they’re just kind of half-written chapters. You know, half-written books that have no end,” he said.

That final product is invaluable to graduate students because it represents years of work, O’Mara said. It factors into job prospects and future funding opportunities.

Department of Plant Pathology Graduate Program Coordinator Susan Kingsbury said government shutdowns can bottleneck years of research, which is especially damaging for those near the end of their program.

“If something goes wrong [or] dies because of the shutdown and the lack of care, or they missed a crucial point where they’re supposed to do something,” said Kingsbury, “their research, their progress has been slowed.”

The CDL reopened Monday, but O’Mara said it will take time to get his experiments back up and running. He’s waiting for new wheat to grow.

“Even though the government has only been down for five weeks, I could be like two months behind,” he said.

Adding to their precarious situation, graduate students have to complete as much as possible for their dissertations while they still have grant funding.

“When the money’s gone, you have to stop,” said Grace Anderson, soybean disease researcher. “You don’t have endless undesignated funds to do whatever you want.”

Anderson knows firsthand how inconvenient shutdowns are for graduate students. Ph.D. candidate Kat Sweeney has been out of her lab since Christmas.

When the USDA-owned North Central Research Station closed, Sweeney had to move her research to a makeshift lab.

“I had an hour or so to get my stuff together and make sure there wasn’t anything hazardous sitting out,” she said.

Sweeney said moving hasn’t halted her research, but all the inconveniences add up.

“Some things you just can’t move,” she said. “I can’t just take all the equipment, all the chemicals, everything and carry it across campus.” She had to leave the centrifuge and the vats of concentrated hydrochloric acid, but she was able to fit her chemicals in a mini fridge. She needs them for her pioneering research on a newly discovered fungal pathogen decimating ohia trees in Hawaii.

Sweeney said the end of the shutdown was a massive relief. Her advisor has been furloughed, preventing her from lending her expertise to Sweeney’s dissertation, which Sweeney is due to defend in April.

When the building reopens Monday, she’ll be able to get what she needs out of her lab, but Sweeney said she’d rather not risk having to move again if the government shuts down in three weeks.

“I’m going to stay put for now,” she said. “On the bright side, I’m meeting a lot of people.”