University of Minnesota regents are looking to refresh board policies governing themselves.

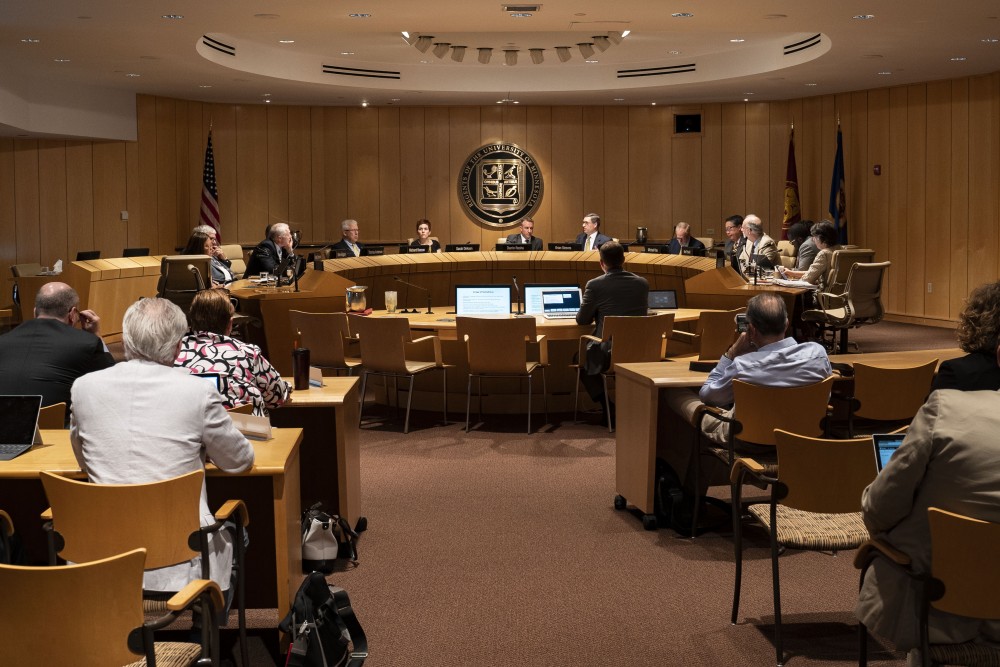

In a robust conversation at the October meeting, regents discussed what changes, if any, they feel are appropriate, potentially editing policies including running for office, removing a member and speaking with the media.

Potential changes are being drafted for further discussion in December with hopes of adopting updated policy next year, Board of Regents Chair Ken Powell said.

“You just need to constantly look at these things to make sure they are still working for you,” Powell said. “You just need to make sure that they’re still current, fresh and relevant.”

Running for partisan office

Several regents indicated current policy requiring resignation upon announcing candidacy for a political office is too extreme. Policy could still require resignation if elected, but some felt drawing a line across all partisan offices is overly broad.

“I don’t know that a partisan office necessarily should disqualify someone, other than if they are elected to the state legislature, that would be the one carve-out I would insist on,” Regent Richard Beeson said in the meeting.

In the past, regents have served in offices such as a school board director or county commissioner without resigning. A change could require regents to disclose the candidacy to the board through conflict of interest procedures.

Regent Mike Kenyanya noted their code of ethics restricts regents from using the prestige of the office for political gain.

“You open the door for someone campaigning to really lean and use their regent title and experience to prop it up,” Kenyanya said at the meeting.

Removing a regent

Also at issue is language requiring a regent to resign. There is no policy for removing a regent, and state law does not address it either.

In 2012, Regent Steve Sviggum resigned after he took a job as communications director for the state Senate Republican caucus, causing some regents to see it as a conflict.

“I decided it might be best, rather than allow something to fester … maybe it would be better to resign,” Sviggum said.

Without a procedure in place it is unclear how the board would handle a situation where a regent was asked to resign but did not oblige.

“I think we have to grapple with that,” Powell said.

Who can speak to the media

Current policy states the board chair alone can speak for the entire board, but regents are parsing how they should speak to the press about their opinions on issues.

“Every regent ought to have the right to speak for her or his self regarding issues of policy or issues of the budget or whatever the issue may be before the board,” Sviggum said. “But I think it’s important that we clarify that we are speaking for ourselves and not for the board.”

Most other Big Ten schools do not have a policy specifically addressing communicating with the media. Pennsylvania State University policy emphasizes the University as a “free marketplace of competing ideas,” but reminds members to always act in the schools best interest.

“Using the media to effectuate or attempt to effectuate a governance outcome that didn’t happen in this room is what … conduct we are trying to get at and make sure it doesn’t happen,” Regent David McMillan said at the meeting.

But Regent Michael Hsu pushed back, saying he doesn’t believe a policy is necessary and the press has a role in informing the public about what happens at board meetings.

“There are very few people … going back on YouTube and watching the meetings and trying to figure out what we say,” Hsu said.

Both the current and proposed language of the policy says regents should be open about their opinions at board meetings and supportive of decisions when they are made.

“We need to operate as a team in the best interest of the University, and that doesn’t mean I’m always going to get my way,” Sviggum said.