At a series of Black Lives Matter protests last week, several bystanders took to their phones to document their interactions with police.

Some University of Minnesota student protesters secured their video recordings on the state’s American Civil Liberties Union server using a cellphone app launched earlier this month.

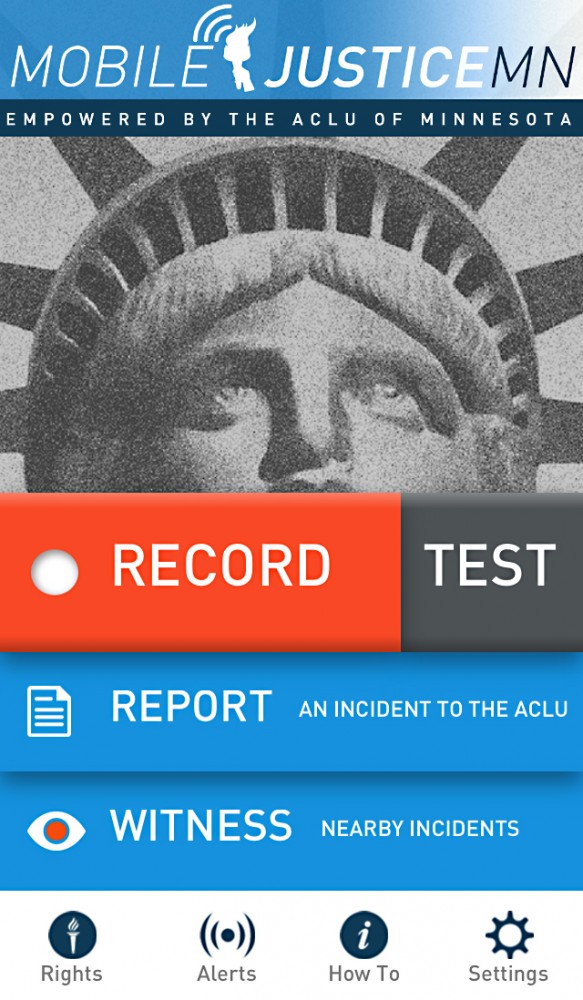

The Mobile Justice app, now available in 18 states across the country, allows users to upload recordings of crime and police encounters in an effort to prevent law enforcement from deleting evidence. So far, officials say the app has been downloaded on more than 10,000 devices

nationwide.

ACLU Minnesota Executive Director Charles Samuelson said the app was created to increase police accountability.

“What frequently happens during these encounters is the police take the phone and delete images and videos,” Samuelson said. “It’s happening all over the country.”

But citizens have the right to record their interations, and deleting the footage can ruin law enforcement credibility, Ryan Pacyga, a Minneapolis criminal defense attorney, said.

“The video doesn’t lie,” he said. “If the police are doing the right thing, then there should be no fear.”

Video, even if it’s recorded on a phone camera, is commonly used as evidence in a court of law, Pacyga said, because it’s not subject to interpretation.

Still, Minneapolis Police Department Public Information Officer John Elder said though police generally aren’t phased when being filmed, bystanders sometimes get in the way of police conduct.

“The most important thing is giving officers space,” Elder said. “I was at the protest, and I was videotaped, and that’s fine. It wasn’t interfering with me doing my job.”

The app can also send text alerts to other app users in the area when someone is recording and wants others to come and bear witness, Samuelson said.

“There was a young woman who was punched in the face [at the Black Lives Matter protest], and I was immediately notified through the app,” University computer science and English junior and Minnesota Public Interest Research Group co-chair Mica Standing Soldier said.

A list of rights in the app can help guide users through police interactions, she said, reminding witnesses to remain bystanders.

Still, police have raised concerns that notifications of a police encounter will cause app users to flock to the scene, Pacyga said, though he thinks the worry is overblown.

“Even if there is some legitimacy to these concerns,” he said, “the public’s interest in knowing what the police are doing greatly outweighs the police’s fear that the app could cause greater disturbances in the street.”

ACLU Minnesota Public Education and Communications Director Jana Kooren said the group worked to sort out kinks, like setting up a server and recruiting volunteers to sift through incoming video footage, before the app was released earlier this month.

“We want to make sure police accountability is in the hands of the people of

Minnesota,” she said.