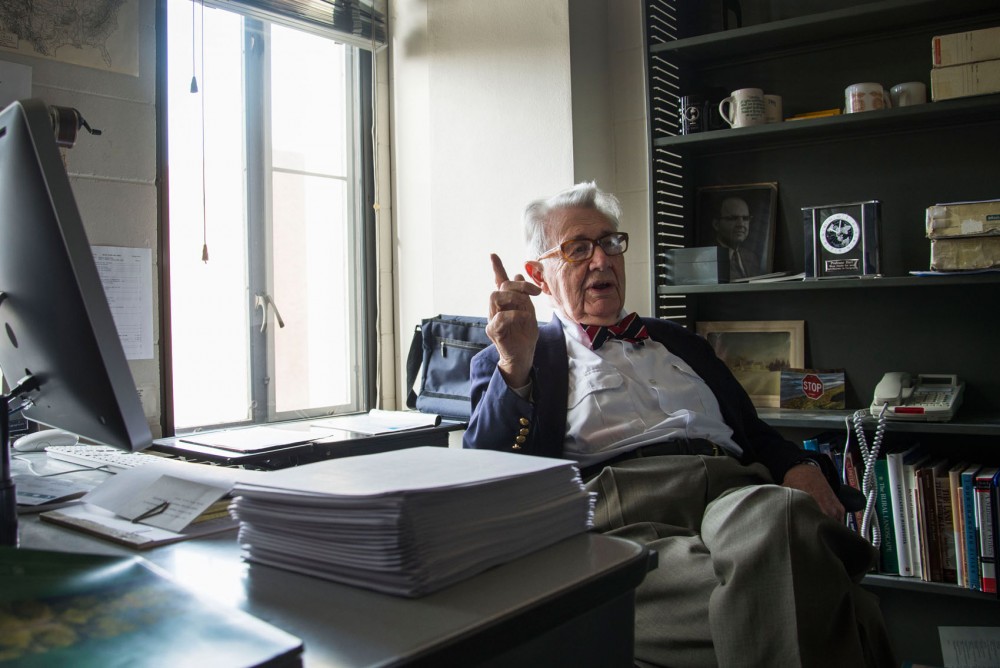

John Fraser Hart has had a lot of fun in his 91 years.

The World War II veteran has traveled the world, taught countless students and despite his retirement this spring, says he’ll never stop

being a geographer.

The University of Minnesota geography professor’s retirement will end a 48-year stretch of teaching a self-estimated 40,000 students, and it comes during a time of uncertainty for school officials. With the baby boomer generation aging, the number of faculty retirements across the University is expected to rise.

The phenomenon has administrators worried about losing top-tier, experienced researchers and professors. But by allocating funding toward attracting and hiring younger academics, they hope to pre-empt the ensuing shortage.

Nearly 40 percent of Twin Cities campus faculty members are 55 or older — a demographic the University categorizes as near the traditional retirement age, though there is no mandatory retirement age.

Compared to other colleges, the problem is more pronounced in the College of Food, Agriculture and Natural Resource Sciences, where the average age of faculty members is about 54 years old.

The college is projected to lose 32 percent of its 262 tenure and tenure-track faculty over the next decade, said Brian Buhr, the college’s dean.

“We’re losing a huge amount of intellectual capacity,” he said.

But CFANS is precautious in its planning. It plans for faculty members to retire by age 70 and bases its 10-year projections on that number, whereas most colleges go off of the number of faculty members who have indicated that they will retire in the near future.

Vice President for Academic Affairs and Provost Karen Hanson said it’s difficult to predict when and in which departments the school’s number of retirements will increase.

And even as educators age, she said, they still want to work.

“There’s no fixed retirement age. Even though boomers are getting to the retirement age, the work most faculty members do doesn’t require heavy lifting, it requires heavy intellectual lifting,” Hanson said. “Many want to remain engaged in academic thinking.”

Buhr said employees are working longer hours than ever before and they’re retiring later, adding to the difficulty in predicting retirement rates.

When professor Hart turned 70 in 1994, a law that required retirement at his age was repealed. Hart said after that, he and his same-age colleagues didn’t leave the school because they were no longer forced to.

“I stuck around because I could,” he said.

Last year, the average retirement age at the Twin Cities campus was 69.

Hanson said the University’s phased retirement option, which allows faculty members to slowly disengage from the school, helps administrators predict when a professor may retire. The policy allows faculty to work less than full time for up to five years and still receive full benefits.

“It allows faculty members to get a sense of what it will be like to move into retirement,” Hanson said.

Ken Horstman, the University’s director of employee benefits, said 39 of last year’s 119 faculty retirees took the phased retirement option.

Only 10 faculty members will retire from the College of Liberal Arts this year.

CLA Associate Dean of Faculty Ana Paula Ferreira said liberal arts leaders aren’t worried about faculty retirements, though the college’s average age is relatively old.

Only 15 percent of its faculty pool is made up of assistant professors, who are traditionally younger.

Twenty-six faculty members in the College of Science and Engineering have said they intend to retire in the next five years. And Chris Cramer, the school’s associate dean for Academic Affairs, said overall, the college’s faculty pool is expected to grow as a result of an

increased demand for STEM education.

Jane Glazebrook, the College of Biological Sciences’ associate dean for faculty and academic affairs, said if the last five years are any indicator of the future, the number of CBS faculty members is also expected to grow.

Though the increasing number of retirements could bring a problematic shortage, the open jobs across the University can allow administrators to hire new researchers with less experience and who often receive lower salaries.

“You hate to lose good people, but at the same time, [experienced faculty are] making more money,” he said.

Funneling in younger researchers

The University invests in faculty members who can produce cutting-edge research. To address the impending shortage, administrators have formulated a plan to continue churning out innovative studies.

“Many universities across the nation are facing a shortage in researchers,” Vice President for Research Brian Herman said. “It’s a very general problem.”

Herman said the University is in a good position to attract young scientists because it has major initiatives in popular fields, like environmental science and health care.

The University is aggressively hiring younger researchers to help combat the shortage, and Gov. Mark Dayton’s budget proposal released earlier this year includes room for the University to hire 50 new medical school faculty members.

In the past, Herman said, the University has had the right amount of funding to balance older researchers with younger ones. But receiving federal funding, which supports much of the University’s research, has become more challenging in recent years.

“Competition for funding is getting more and more intense,” Herman said.

Buhr said budget constraints complicate succession planning. He said CFANS will determine which fields will be in the highest demand in the next few years, so it can choose to hire in those areas.

Fewer experienced researchers and more young scientists could also reduce the number of grants the University’s faculty members receive.

A Johns Hopkins study published in January found that young researchers receive less funding for their work because the grant

process favors “systematically incumbent” researchers.

Dan Knights, a computer science professor who received his Ph.D. in 2012, said when researchers don’t have a long track record of successful projects, it can be hard to secure funding.

But he said there are initiatives in place — such as one led by the National Institutes of Health — that give grant preference to young researchers.

Knights said writing grant proposals can be challenging for researchers who have never done it before, so older professors will sometimes help their younger colleagues with drafting the requests.

“Grant writing is an art,” Glazebrook said.

CFANS has attempted to smooth out training for its new hires by placing them in departments with experienced professors who are near retirement so that once those employees leave, the newcomers will feel confident in their work.

But paying a new researcher alongside an older one isn’t easy to fund, Buhr said.

Despite the developing complications that are expected to come with faculty retirements, school officials are still optimistic about the University’s future.

“There will be a lot lost as the baby boomers retire,” Provost Karen Hanson said. “I have faith that there’s great talent coming up.”