In response to gaps found in a literature review on the benefits of nature-based learning, University of Minnesota researchers are recommending further research to make the learning more accessible.

The gaps are addressed in a research agenda, which will be published next week. The researchers were surprised to find strong converging evidence for the benefits of nature-based learning, such as rejuvenated attention, stress reduction, increased self-discipline and better engagement. But there is also a demand for specific analysis so these ideas can more easily be applied in educational settings.

The research agenda asks experts to further study the benefits of nature-based learning so people like teachers, city planners and legislators can apply that knowledge to their work, said Pediatric Neuropsychologist Catherine Jordan, a researcher on both projects.

“Nature has traditionally been seen as sort of a luxury. … And that often results in inequitable access to nature,” Jordan said. “What our message is, is that no, nature actually has to be taken seriously as a necessity in promoting children’s development and their educational outcomes.”

Interactions with nature can result in improved results academically and can also increase development and characteristics like “perseverance, critical thinking, leadership and communication skills,” according to the literature review.

“We’re basically trying to guide, [to] push the field, or these many fields, that contribute to this idea of nature-based learning to ask the most pertinent, most critical research questions and to answer those using the most rigorous methods,” Jordan said.

While the literature review focused on the effect of nature-based learning on young children, Jordan said the results of the study can be generalized to include college students.

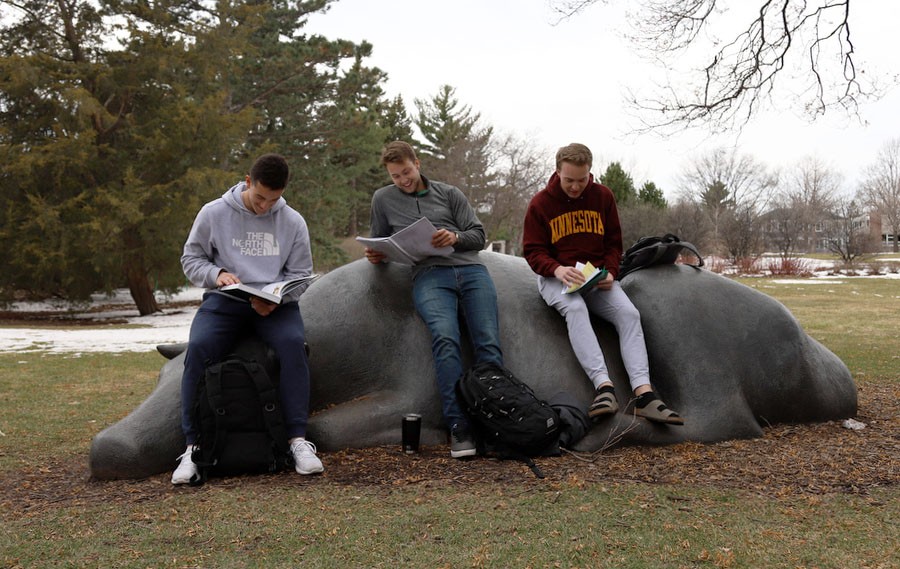

“If you have a campus in the middle of the city, like we do … the role that nature has to play is even more critical,” said Michael Barnes, an environmental psychology graduate student who worked on the literature review. “Those natural spaces that we have here on campus are even more important and should be not leftovers, but thought of.”

Even small adjustments, like adding planters along walkways or sprucing up a courtyard outside of classroom and office spaces, can provide restorative benefits, Barnes said.

Some of the questions posed in the research agenda aim to gain more information about how teachers can successfully incorporate nature-based learning into their curriculum and how factors like age, gender and socioeconomic status affect a child’s learning.

“It not only relates to being a better place, a place where students want to be, but also can actually impact the learning that’s going on in these places,” Barnes said.

To be able to apply nature as a solution, practitioners like Sheila Williams Ridge, the director of the University’s Shirley G. Moore Lab School, are looking for heightened applicability from research.

“The research agenda is going to influence the way that we are looking at our time outdoors,” Ridge said.

She sees how children can have a difficult time managing themselves in a classroom setting.

“All of those things can be immensely helped by taking children outside an appropriate amount of time. But we don’t know what that time [is], and we don’t know what is the exact nature that they need,” Ridge said. “I think the research agenda is going to help us figure out … those important things about dosage and about defining how much nature is enough nature.”

Correction: A previous version of this story mischaracterized a quote from Sheila Williams Ridge. Ridge was referring to the type of nature that students need.