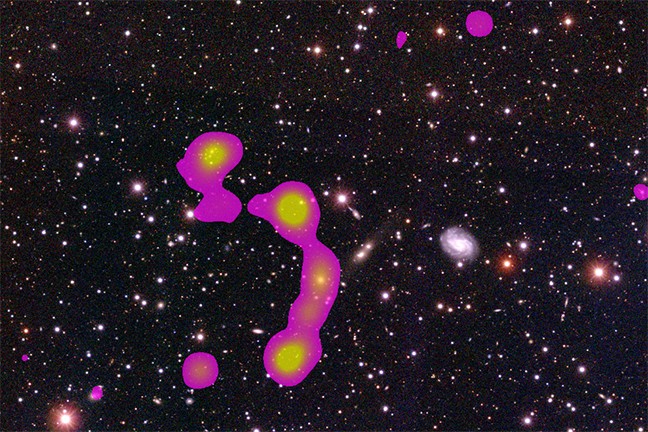

When University of Minnesota astronomer Larry Rudnick found two citizen scientists discussing an abnormal radio structure online, he knew they were on to something bigger.

He brought the pair’s findings to the team he advises for a project called Radio Galaxy Zoo, which helps identify radio galaxy images. Soon, the researchers used the pair’s image to track down a new radio galaxy cluster.

The project is part of Zooniverse, a website allowing everyday people to collaborate with researchers, a practice called citizen science. Co-founded in 2010 by University of Minnesota professor Lucy Fortson, the website is one of many platforms that let everyday people participate in projects like transcribing historical documents or discovering galaxies.

“Citizen science can generate data that is just as good as the data that is collected by professional scientsts — on a much much bigger scale,” said Anne Bowser, co-director of the Wilson Center’s Commons Lab, which studies citizen science.

A case study: Zooniverse

Zooniverse has over 1.5 million participants and 60 projects. There are also thousands in the “beta stage,” where they are evaluated before being opened to collaboration, Fortson said.

The website originated as a single project to identify over a million galaxy shapes. Because of the intense

workload, she decided to create a site called Galaxy Zoo in 2007 to allow anyone to log on and help her team.

Computers struggle at classifying galaxy shapes, Forston said, making it necessary to recruit humans.

“It’s just difficult for computers to provide information about an image, where human beings, our entire visual cortex has developed through evolution to provide highly precise information in an image,” Fortson said.

As the website caught on, Forston and her team conducted a survey to see why participants were interested and found that most people said they wanted to contribute to research in general. In response, Forston said, the team expanded their approach to include various disciplines in addition to astronomy.

Zooniverse now houses Galaxy Zoo as one of its projects.

Citizen science benefits

Rudnick said without crowdsourcing from citizen scientists, his Radio Galaxy Zoo project may have never started.

“If I have a project that I think is going to take a month or two of a student’s time … it’ll get done,” he said. “Suppose it’s gonna take 1,000 years, you’re not gonna start the project,” Rudnick said.

The Huntington Library in San Marino, Calif., turned to Zooniverse to help decode civil war telegrams. The decision was largely motivated by the potential to reduce the the project’s timetable, said project lead Mario Einaudi.

“For an individual at our institution to do that, working full time, it would take 3-4 years to do everything,” he said. “Here we can do it in much shorter time, and probably [with] much greater accuracy in the end.”

Rudnick said researchers are also analyzing citizen scientists’ click data to see if they find a way to let computers automate the identification tasks that citizen scientists have to do.

“It’s difficult for computers to give classisifications on the shape of a galaxy. But in the 10 years [of] Galaxy Zoo, computers have been getting smarter and smarter. But one of the things computer algorithims need is a lot of training,” Forston said.

Battling skepticism

When Forston first opened her galaxy identification project to the internet, she said it was met with some skepticism from the academic community regarding data quality.

To combat this, Forston said, Zooniverse is now highly selective in what projects they accept for collaboration.

Anyone can submit proposals for projects to be worked on through Zooniverse, but it has to go through beta testing first to allow staff to determine if the project has potential to have high-quality data, she said.

“For us it was absolutely critical, if a research team wanted to work with us, they had to have a very good probability of producing a peer reviewed journal paper,” she said.

Bowser, the Wilson Center’s Commons Lab director, said that because of all of their peer-reviewed papers, the citizen scientist community has proven “over and over and over again” that data quality is no longer an issue.

“Within the citizen science community, that [skepticism] really elicits an eyeroll,” Bowser said. “Citizen science is one of the only tools that can collect enough information in enough places to solve really global challenges,” she said.