By the end of the month, all University of Minnesota students, faculty and stakeholders will be required to use dual authentication when logging onto any University server, including MyU, G Suite and Canvas.

An effort nearly a year in the making, the roll-out of Duo Security was prompted by the need for greater protection from increased identity theft and phishing attempts. Some University staff and students have had financial aid, paychecks and tax returns stolen as a result of password theft.

Members of the University recognize the need for increased security measures against cyberattacks, especially in higher education institutions. Experts weigh in on how exactly the University keeps student and faculty data secure.

Should I be worried about a data breach at the University?

Well, it depends on who you ask.

“Are people trying to attack us? The answer is absolutely,” said Brian Dahlin, chief information security officer for the University. “We get attacked every second. It is just a constant that is an attribute of the internet.”

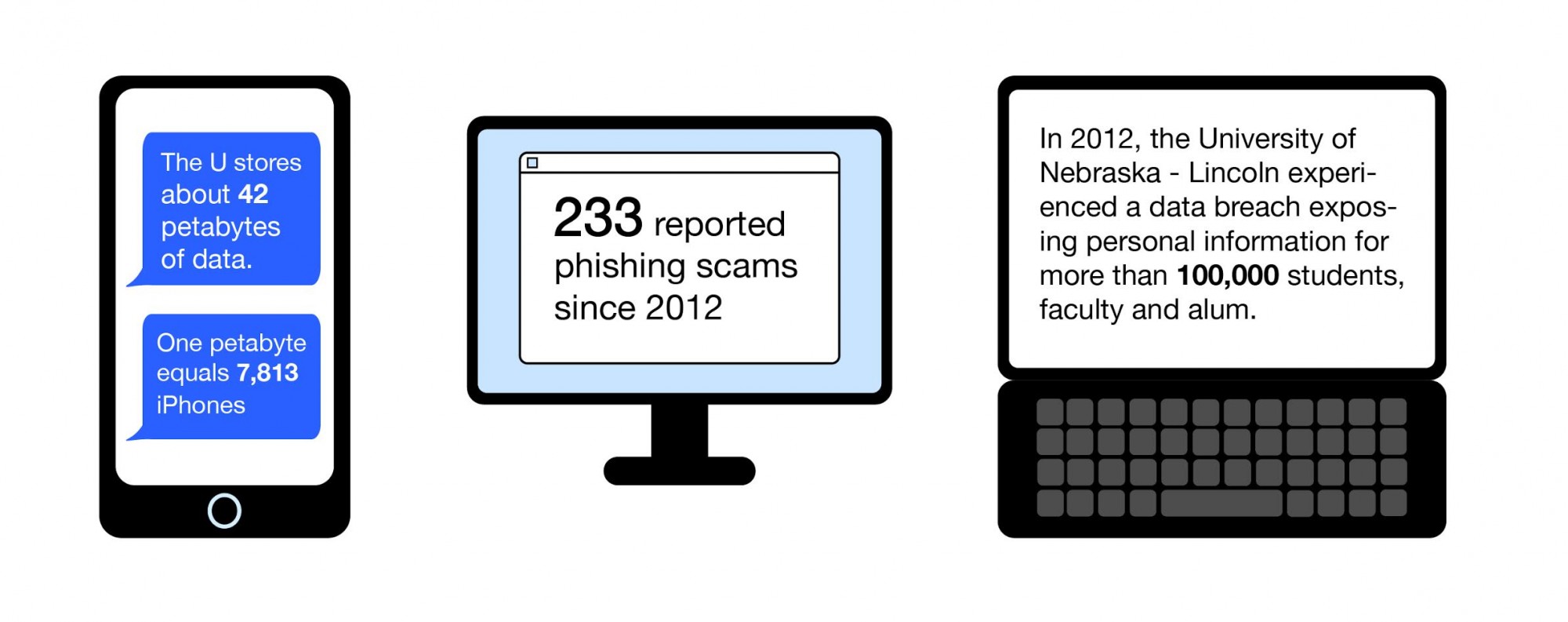

There have been at least 233 reported phishing scams since 2012, according to a University IT page. Mandatory Duo security implementation was a response to these attacks.

However, that does not mean it is time to run the red alarm. Dahlin said in his eight years of experience as chief information security officer, he has not dealt with any massive data breaches. According to IT, nothing substantive has been reported and the University is required by law to undergo ongoing risk assessments.

That is not to say that data breaches have not occurred in the past — they are just not all related to the trope of a hacker hunched over a desktop in a dimly-lit basement.

“It doesn’t necessarily mean that that information was put into the hands of some malicious actor or hacker or something along those lines. It could be as simple as an individual sent somebody personal information to the wrong email address,” Dahlin said.

Andrew Odlyzko, a professor at the University’s School of Mathematics, said that people should not let data breaches or concerns for cybersecurity keep them up at night.

“Cybersecurity is very important, but it’s not an imminent danger,” he said, adding that people are too quick to think of the worst case scenario. “Most of the time, the worst case doesn’t happen.”

So, just how much data does the University store?

The short answer: a lot.

“The University is a small city,” Dahlin said. A small city stores an awful lot of data: according to the Office of Information Technology data storage team, the University stores about 42 petabytes.

Peta-what?

A petabyte is a memory unit equivalent to 1 million gigabytes.

For some context, say you have an iPhone 7 with 128 gigabytes of storage. To fill one petabyte, you would need approximately 7,813 iPhones. To fill the University’s storage capacity, you would need more than 328,000 iPhones.

That’s a lot of data. How exactly do we store it all?

It depends on what kind of information is stored.

Data is retained by the University for different periods of time depending on what exactly the data is. Undergraduate admissions applications and advising records are stored for up to 5 years; litigated complaint records and billing disbursement information are stored for up to 10 years.

The data is also afforded different protections and access based off its security level or relation to FERPA and HIPAA laws.

FERPA and HIPAA … what are those?

“FERPA is the most comprehensive or major law in the world of student data privacy,” said Stacey Tidball, director of the University’s Continuity and Compliance.

Enacted in 1974, FERPA determines what student information is publicly available and what is private.

Student data available to the public includes email address, phone numbers and physical address, according to University policy. However, students do have the opportunity to suppress what information is publicly available.

Lori Ketola, director of the Health Information and Compliance Office, explained that there are state and federal regulations that deal with protecting health data.

Health data, such as Boynton Health records and research, are subject to HIPAA, a federal law protecting individual health information. Minnesota state laws restrict even more information than HIPAA.

Like FERPA breaches, HIPAA Security Officer Rick Wagner said “most of the HIPAA breaches that occur are related to human error,” such as accidentally emailing the wrong person and compromising personal data or misplacing a laptop.

How do we stack up to other Universities?

Well, that is hard to say. While there have been data breaches in the past, none have been as severe as other breaches at other Big10 schools.

For example, in 2012, the University of Nebraska – Lincoln experienced a data breach potentially exposing personal information, including social security numbers, of more than 650,000 current and former students. Rutgers University had to spend $3 million after a series of cyberattacks took down their computer network four separate times during the 2014-2015 school year.

Cybersecurity across higher ed can be difficult to compare as University structures, sizes and budgets differ.

“We’re talking to each other. We’re gathering ideas from each other,” Tidball said. “Different institutions are more innovative here and less innovative there. I don’t get the sense that there’s someone across the board doing everything perfectly.”

So how is the University doing overall?

When compared to standards set by the Higher Education Information Security Council, the University scores equal to or better than the average cybersecurity scores in 14 of 15 categories.

One solution Dahlin suggested to help bolster the University’s cybersecurity was increased automation, in which technology responds to cyber attacks or vulnerabilities.

However, third-year electrical engineering student Sina Roughani pointed out flaws in the current University system.

Roughani said he found vulnerabilities in the forms student filled out for the parking lottery in the Parking and Transportation Services Department, which have since been resolved. Roughani advocated for increased student information privacy last year.

“[The University] certainly isn’t on the leading edge for making sure that they’re protecting against major vulnerabilities, like on the people search site. That one is currently vulnerable to a couple of attacks that can basically take the site down,” he said.

What’s next?

“Twenty years ago or so you didn’t see [online] security teams exist at all. You also had very little guidance on what people should be doing in security to try to help secure the organization,” Dahlin said.

According to David Du, director of the University’s Center for Research in Intelligent Storage, one of the greatest challenges in data storage is simply keeping up with technological advances.

Cloud storage, for example, has a seemingly limitless lifespan, whereas floppy disks, which reached peak popularity during the mid ‘80s, only had a lifespan of five to seven years. It can be a constant game of catch-up, he said, but the University has no solid plans to move data to another medium.

According to Odlyzko, cybersecurity is all a balancing act. Technological infrastructure can always be more secure, but human comfort often imposes a limit.

“The dual system is not the strongest form of two factor authentication. There are certain ways to subvert it,” Odlyzko said. “We could go to a more secure route where you carry a special token, which lets you authenticate yourself. But we don’t do it. Why? Because it’s less convenient.”

Dahlin said that the University is on par with other institutions of higher education, but the cybersecurity team constantly tries to keep up with innovation in a rapidly evolving world.

“It’s not just us – everybody who is on the internet is getting attacked in some way,” Dahlin said. “It’s certainly a threat to us, but with cybersecurity we have a defense mechanism.”

Correction: a previous version of this story incorrectly described an app. The app is called Duo Security.

This article has been updated.