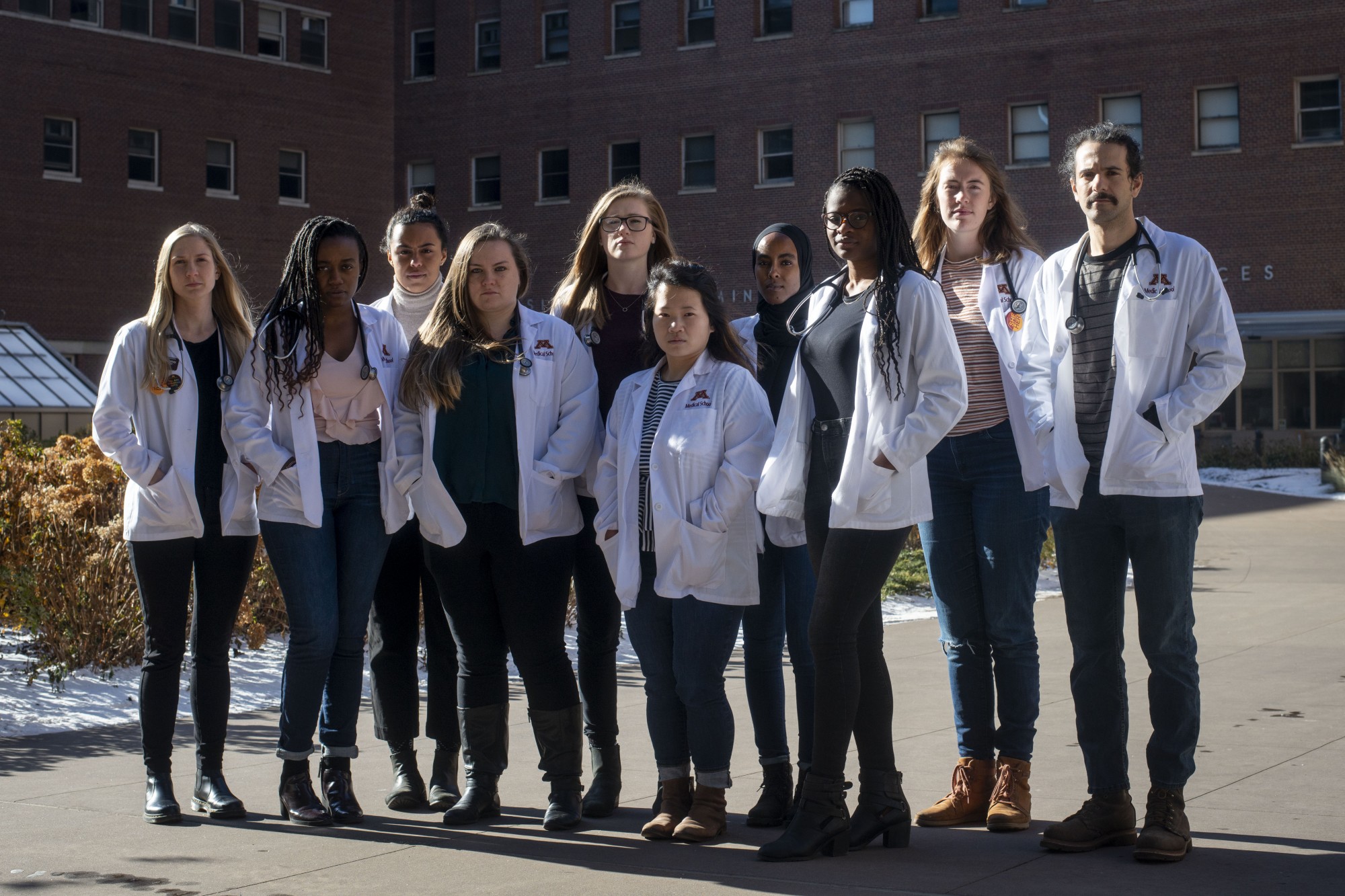

A group of second-year medical students is trying to improve treatment of patients of color in a historically white healthcare system.

The University of Minnesota’s chapter of White Coats for Black Lives was established in 2014 and works to increase diversity and awareness of racism in the medical field. WCBL is especially focused on curriculum, which members said is not representative of the diversity of patients they might see in the field.

The group recently held its second annual Health Equity Week, consisting of lunch lectures and evening workshops to address a disconnect between race-related issues and health education. The group also took on a lack of diversity practitioners within the field.

“We want to make sure that we’re training physicians who will be capable of taking care of patients of color in the future,” said WCBL officer Michelle Kihara. “Similarly, highlighting the experiences of minority physicians and health care workers and how to be an ally.”

Members said that diversity in healthcare is important at the University, which is one of the largest producers of physicians in a state with some of the worst racial health disparities in the country.

Julia Weston, an officer in WCBL, said it was important for the University to address these issues to better prepare their future physicians for Minnesota’s diverse population.

WCBL officer Salma Hassan pointed to a 2016 University of Virginia study, which found that bias or false beliefs about biological differences between black patients and white patients held by some medical professionals can contribute to disparities in pain treatment.

“If you’re a medical student and you believe that black people feel less pain than white people, imagine what’s going to happen when you’re in the emergency department and someone comes in with a fractured bone,” Hassan said. “You’re going to give [the patient of color] Tylenol when, if they were a white person, you would’ve given them a narcotic.”

WCBL officer Megan Lucas said that, despite researchers with the Human Genome Project disproving the theory that race was a biological factor in 2003, many medical students and physicians still believe it is.

Other studies also show that patients of color often wait longer in emergency rooms than their white counterparts. They also wait longer for pain medications, often in comparatively lower doses and have higher maternal mortality rates.

Evidence suggests racial discrimination triggers a stress response which, when repeated over time, can cause depression, anxiety, insomnia, heart disease, skin rashes and gastrointestinal problems, according to a 2004 University of Miami — Coral Gables study.

Physicians of color can be discounted by their peers and superiors, an added stress when providing care, members said.

“As a future white physician,” Lucas said, “I don’t think it’s just my peers of colors’ job to address this. This is absolutely not their job.”

WCBL members said the group has met with University administration and the Medical School curriculum team to discuss addressing bias in the curriculum.

“Things move slowly,” Hassan said. “We haven’t gotten a ‘no’ or ‘this is not going to happen’ or anything like that. We’re continuing to work with them.”

The group sent out a survey last year to gauge student’s satisfaction with race and racism in the curriculum. The group intends to use data collected from that survey along with data collected during Health Equity Week to further discussions.