After over half a century of bloody civil war, Colombians expect to know peace again.

After over half a century of bloody civil war, Colombians expect to know peace again.

The Colombian government reached a heated peace agreement with a Marxist guerrilla army — the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, also known as FARC — that the country will vote on this October.

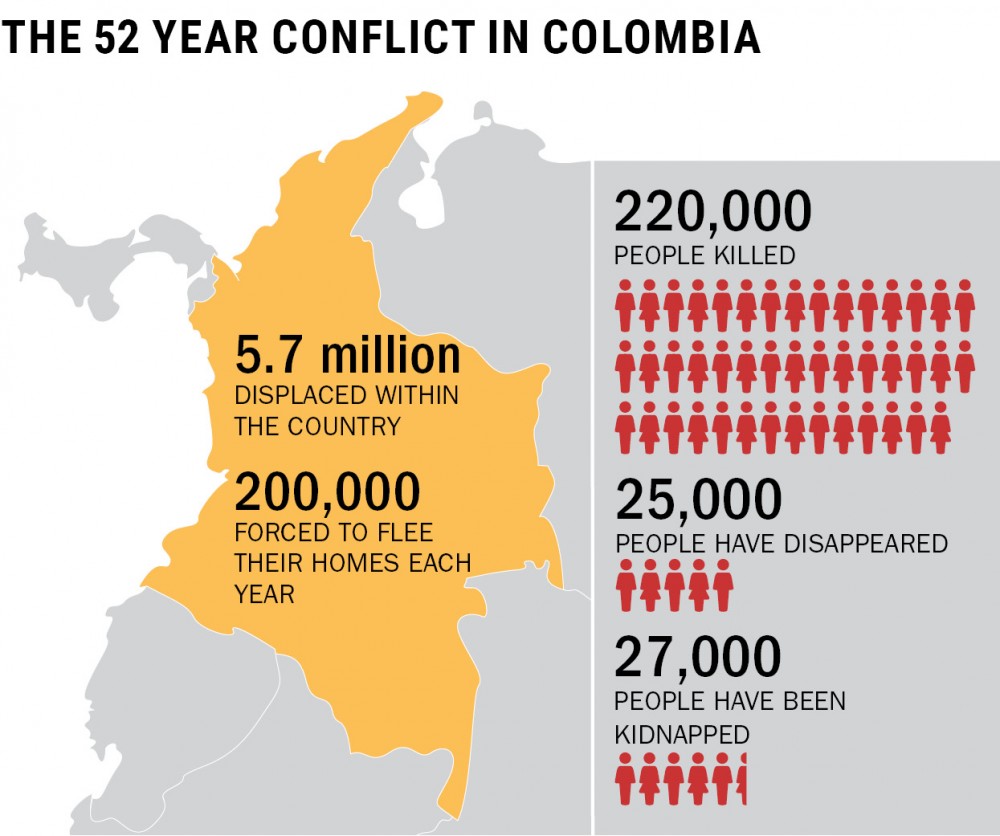

During the 52 years of war, thousands of Colombians fled the country. Some ended up in this state, and others attend the University of Minnesota.

Julian Preciado, a third-year biomedical engineering doctoral student, said his father was offered a job in Kuwait in 2001, and they saw no reason to stay in Colombia.

“My parents were thinking that it didn’t seem like [the war] was going to get any better anytime soon, and there was a lot of violence going on in the surrounding regions, so they didn’t really want to stay,” he said.

While Preciado said his family was fortunate to be able to move away and escape the country’s violence and eventually move to the U.S. — many others were forced to ride out a civil war that seemed to have no end.

Colombia has the largest number of internally displaced people in the world, said Greta Friedemann-Sanchez, an associate professor at the University’s Humphrey School of Public Affairs.

The decades-long tale of kidnappings, forced moves, murders and economic turmoil has directly impacted more than 17 percent of the country’s population, said Lisa Hilbink, a political science professor at the University.

Hiblink said Colombian women and children were particularly vulnerable because they were more susceptible to sexual assault and malnutrition.

Natalia Morales, a communication studies senior, lived in Colombia until 2011 when she moved to the U.S. to study English.

Morales said she lived in a safer region but saw the effects of war everywhere.

“We have a lot of family friends who have disappeared … not because they’re involved in politics [but] because of the guerrillas,” she said. “Every day, Colombians are dying.”

Morales said the bloodiest parts occurred in rural areas, so inhabitants fled to the cities. The influx of people created job and housing scarcity. Sometimes, she said, those who can’t find a job or afford housing ended up living in the streets.

“That’s where all the social problems start in Colombia – [the feeling of] insecurity,” Morales said.

Now, unrest continues as the government deliberates and prepares to sign a peace agreement with FARC that some have said is unfair and doesn’t offer reparations for those affected by the war.

Preciado said he wants the agreement to be signed and passed by popular vote on Oct. 2,, but he isn’t satisfied with its terms.

“I still have some issues with it in terms of justice and people being held accountable for … the crimes they committed, but I think it will at least stop the violence,” he said.

Friedemann-Sanchez said there are several highly controversial components of the accord, like how members of FARC would be paid a sum to aid their re-integration into society.

In addition, some rebel fighters would be pardoned, which is difficult for those who have been terrorized by them, she said.

Morales said she wants the agreement to pass and hopes it would improve Colombia’s economic situation.

“Nobody wants to invest in a country that has violence,” she said. “We have lost everything.”

Though Morales understands why many people take issue with the peace accords, she said it’s a necessary step to move forward.

“I’m a young person, and I’m speaking about my future and the future of the next generation — my kids, my grandkids,” she said. “I want them to grow up in a country were there’s no war.”