To a grid-oriented, common-sense-buyer Midwesterner like me, California is a topsy-turvy place. The state’s GDP has overtaken that of Great Britain as the fifth-largest economy worldwide, and Silicon Valley is a pretty significant governor of American lives and legislation. California has the largest billionaire population in the U.S., but San Francisco also has a homeless population that plenty of us had thought we’d eradicated along with Hoovervilles. California is the most populous state in the nation, and 98 percent of the state is in a drought, 44 percent of which is at the “exceptional” level, the most catastrophic level. California is the fifth-largest food supplier in the U.S., yet farmers can sell water for more than the acreage equivalent to crop output. California might be a real-live opposite land. These directly feed into the other California feature: the annual wildfire debacle going on right now.

The Kincade Fire in northern California and the Getty Fire in southern California are ongoing, in addition to Saddle Ridge, Tick and Burris fires. These last three are mostly contained, and the Getty Fire is technically not a “Cal Fire” incident as of Oct. 28, but it’s still plain to see that these fires and their predecessors in recent years are indicative of a larger trend. California is a convergence point for a lot of climate karma.

First, the U.S. has had a habit of artificially suppressing fires. Smokey Bear spent a few decades saying that “only you can prevent forest fires.” Unfortunately, this resulted in suspending all the small, natural fires, and so much vegetation that should have naturally been burned in forests across the country has instead compounded into fodder for a massive, sometimes uncontainable fire. Multiple small fires are smaller than one all-consuming one, but we have backed ourselves into the corner of the latter.

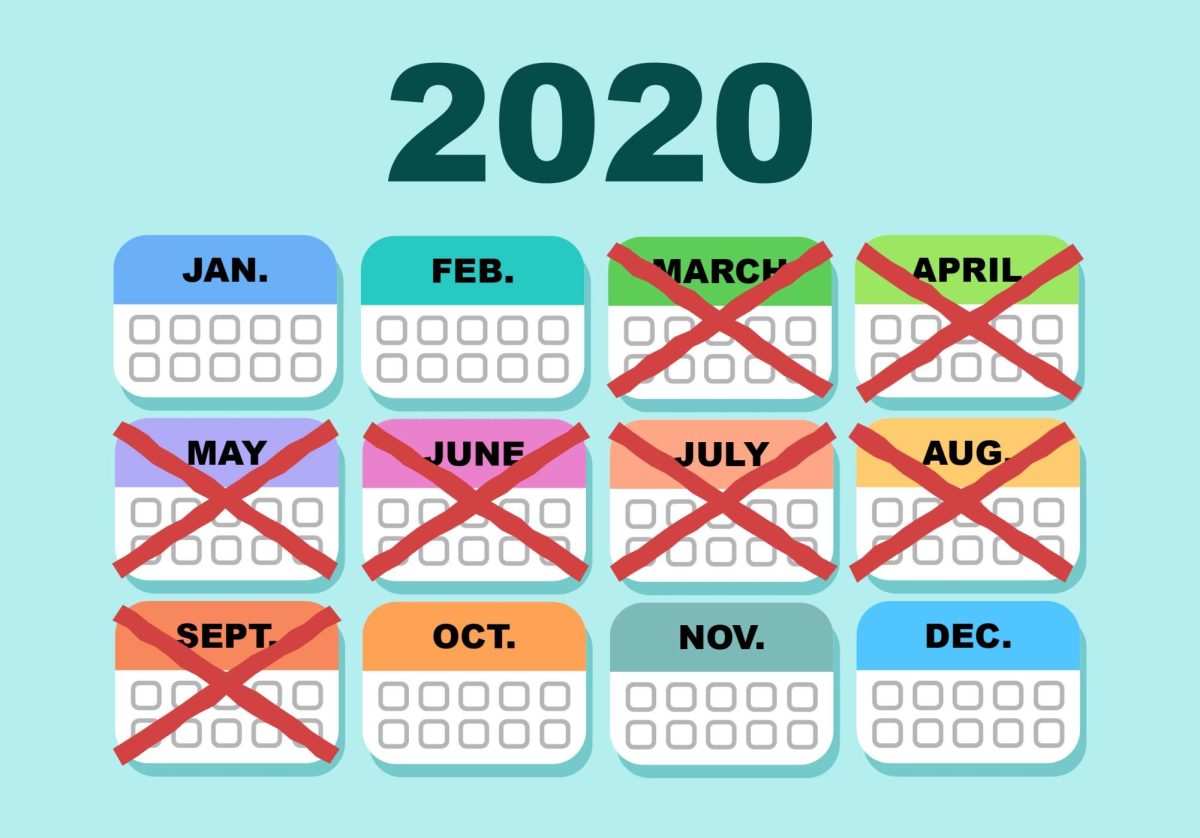

Then there are the rest of the cascading reasons for California fires. California is dry and hot, and it will only become drier and hotter. California has demonstrated two fire seasons: June-September and October-April. These affect different parts of California. The former is in high-elevation, inland, forested areas, and the latter is in more populated, urban areas — but you are correct in thinking that there are no leftover months. Next, 40 million people live there. Again, it is the most populous state, and with every human, there is a greater statistical chance of an accidental man-made spark. And finally, there are the Santa Ana winds. As anyone with any culture remembers from Randy Newman, “Santa Ana winds blowing hot from the north/We was born to ride.” They’re strong, dry, warm and travel southward into Southern California and Baja California—all of these characteristics literally fan the flames.

That people should just move out of an annually combustible state seems facile to someone in a pitch meeting in Minnesota. But nothing is ever that simple. If someone started rolling a five-ton concrete ball at you, you could try to stop it with your body and you would die. Or you could just get out of the way and let it keep rolling, and it is possible that it will just keep rolling forever and no one will get hurt. We know that’s not true, but stopping the ball – or restructuring the state of California – is so unrealistically herculean, that you know what? We’ll move there for a job anyway.