Dana Maltby and Cam Torgerud paint in total darkness.

The two members of the tight-knit Minnesota light painting community capture light to create images. Light painting requires an absence of ambient light, so artists must head underground or wait until sundown to do their work.

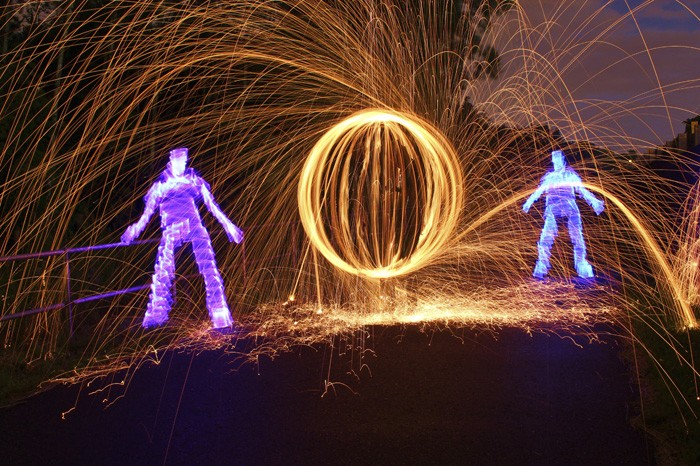

Their cameras are set to hold an exposure for thousands of times longer than usual to capture streaks of light, turning any flashlight or LED into a paintbrush. The result is a surreal and colorful photograph that seems to bend time in a way that’s almost ghostly.

The local practitioners of this craft are a close group. Unlike the modern graffiti scene, the style of which can be traced back to scribblings on New York City subways in the 1970s, light painting got its start as a global art form spread via the Internet. Each community is grassroots and tends to be decentralized.

“There’s usually only one [light painter] per state and sometimes one per country, so the fact that [the Twin Cities] even has five is impressive in itself,” said Maltby, who goes by the moniker Twin Cities Brightest.

Midwestern modesty aside, local painters, including Maltby, took two of the top six positions at the first International Light Painting Award earlier this fall. It’s nice recognition for a group of people who’ve learned the methods together.

Torgerud, aka Light The Underground, remembers when the whole cadre would get together on weekends to shoot photos and swap techniques.

In the community, “You can ask anyone anything. No one tries to be really secretive,” Torgerud said. “A lot of inspiration comes from seeing other people’s photos. In fact, the first light painting I saw was a Twin Cities Brightest.”

There’s a constant exchange of ideas about the best way to expose a photo, locations to shoot at or clever new uses for common handheld light sources.

There’s a strong connection between urban exploration and light painting, giving each region’s art a connection to its history, Maltby said.

European artists can paint in 1000-year-old cathedrals, and the coasts have urban jungles. In Minnesota, it’s “the grain elevator and sandstone milling tunnels on the Mississippi River. It’s the coolest, least light-polluted area and part of Minnesota history,” he said.

A few light companies offer gear sponsorships, and the winners of the International Light Painting Award did receive prizes of premium photography equipment, but the field, like most street art, remains a place for amateurs.

“A lot of people are trying light painting,” Torgerud said, “but not many really revolve around it like we do.”

As digital cameras become increasingly powerful and accessible, almost anyone can make a simple light painting in a blacked-out room.

The art form is still in its infancy, and there are many frontiers left to explore.

Maltby said that sense of exploration still calls to him.

“Pushing myself and not being able to give up, basically doing something that no one has done — that’s what keeps me coming back.”