With higher education among the casualties of the Great Recession, students are left to bear a larger burden of the lost revenues.

Higher education has taken up less of the state’s spending pie since the Great Recession in the late 2000s. Facing competing priorities and declining student enrollment, Minnesota’s Legislature spends less of its General Fund on higher education than most other Midwestern state governments.

“What we see in many states is that post-recession funding levels become a new normal to some extent,” said Aaron Horn, Midwestern Higher Education Compact’s vice president of policy research. “A few states have fully recovered, and Minnesota has recovered significantly, not fully.”

The state budget’s largest bank of money is the General Fund, which precludes special grants, federal funds, bonds or dollars dedicated for specific causes, like fuel taxes.

Rep. Gene Pelowski, DFL-Winona, said higher education was among Minnesota’s greatest cuts following the Great Recession. From 2011 to 2012, higher education spending as a portion of the General Fund was slashed from about 18 percent to about 8 percent, or $3 billion to $1.3 billion.

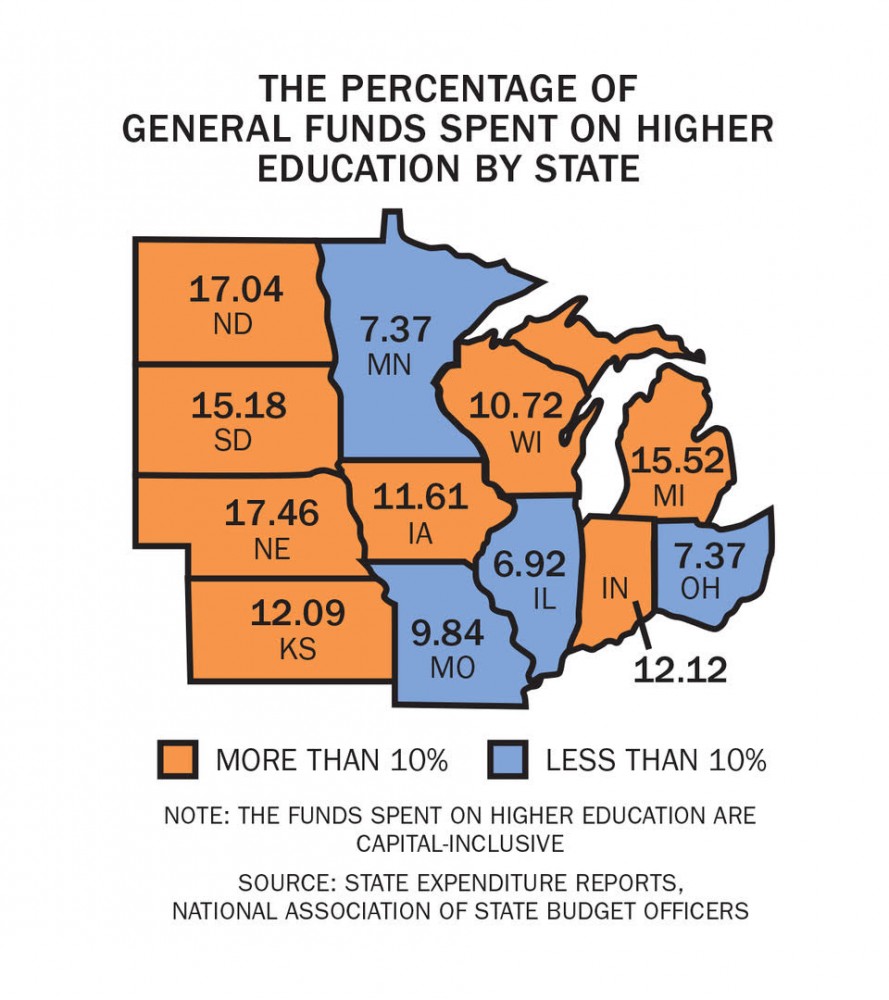

Since then, higher education spending, including infrastructure, has stagnated at around 7 percent of General Fund expenditures.

Besides Ohio and Illinois, Minnesota allocates less of its General Fund toward higher education than the rest of the Midwest. North Dakota tops the list at 17 percent.

Postsecondary enrollment throughout the state has declined since peaking in 2010, cutting into another funding source: tuition. Minnesota student enrollment fell by nearly 46,000 from 2010 to 2017.

“If you have less kids enrolled, should you be spending more money?” said Sen. Rich Draheim, R-Madison Lake, vice chair of the Senate Higher Education Committee.

Thomas Sanford, finance and accountability manager for the Minnesota Office of Higher Education, said economic downturns tend to see increased enrollment, while the opposite is true during upswings — and as enrollment falters, funding needs grow.

“Tuition revenue goes up when the economy’s doing not-so-great because more students are enrolling,” Sanford said. “It’s at the same time when those enrollments are increasing that the state budgets are likely to be at their weakest point in a period of recession, and the state’s able to do the least in terms of supporting public higher education.”

At peak enrollment in 2010, tuition overtook state appropriations as a larger part of Minnesota higher education budgets for the first time, according to the Midwestern Higher Education Compact’s 2017 Higher Education in Focus Report.

“The ongoing discussion should have been that if we are making cuts, and we are doing these types of tuition increases, what’s the impact?” Pelowski said. “And I think now we have a rather vivid picture of the impact: record student debt.”

With fewer students, state dollars go further per student.

Minnesota’s appropriations per student have increased nearly 36 percent from fiscal years 2013-2018, the highest in the Midwest, according to the 2018 State Higher Education Finance report by the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association.

State appropriations have risen for programs like K-12 education and Health and Human Services since the recession, which, unlike the University, the Legislature is constitutionally obligated to fund.

These programs also have limited funding sources, leaving the responsibility to the Legislature to keep them afloat. But lawmakers are “fully aware” higher education funding can always fall back on tuition, said Regent Steve Sviggum, former Minnesota Speaker of the House.

Draheim said he has been pushing Minnesota higher education to be innovative and make internal cuts because K-12 and healthcare needs are growing.

“We have an aging population. We have the silver tsunami, whatever you want to call it,” he said. We’ll have a statistical deficit of people entering the workforce.”

The State Higher Education Executive Officers Association found while state appropriations are stabilizing, state funding for higher education has only halfway recovered from the Great Recession.

As the University consistently works within strained resources, officials will continue adjusting to the state’s competing priorities without compromising the school’s mission.

“Costs go up every year – just to maintain our current scope, let alone to enhance programming and services – and with limited increases in state support and justifiable goals to hold tuition down, we must look to efficiency gains and spending cuts to balance the budget,” said Julie Tonneson, University budget director, in an email. “I don’t see that scenario changing in the near future.”