Of the nearly 300 sexual assaults reported on Minnesota college campuses last year, 47 — the largest number in the state — were at the University of Minnesota, according to a report released Thursday.

The report, released by the Minnesota Office of Higher Education, was compiled after a law passed in 2015 by the state Legislature required post-secondary institutions to report sexual assault data to the state. The report comes amid intense scrutiny of how colleges and universities nationwide internally handle sexual misconduct cases.

Of the 47 assaults reported at the University, 15 were investigated by the University and less than 10 were reported to police.

To protect identities, the report didn’t list specific numbers if there were less than 10 reports for each statistical category — categories like the number of cases reported to law enforcement, number of students found responsible of sexual assault and cases closed without resolution.

“It probably is a snapshot of what goes on in greater society,” said Caroline Palmer, Minnesota Coalition Against Sexual Assault spokeswoman and legal affairs manager. “People report, and they might not have a good experience when they report, and they decide they don’t want to go further.”

While the report didn’t list punishment for students, data obtained by the Minnesota Daily through public records requests shows that sanctions for students found responsible for sexual assault in 2015 ranged from a one year suspension to expulsion.

As part of their penalty, University students who were found responsible for sexual assault were often banned from University housing and placed on probation.

Of the two expulsions in 2015 that the University disclosed, one of the students was expelled after he was found responsible for two separate sexual assaults.

Included in the data was Daniel Drill-Mellum. Drill-Mellum was recently sentenced to six years in prison for raping a University student and another woman.

At the University, he was found responsible for at least one sexual assault and suspended from the University for 10 years, according to the data.

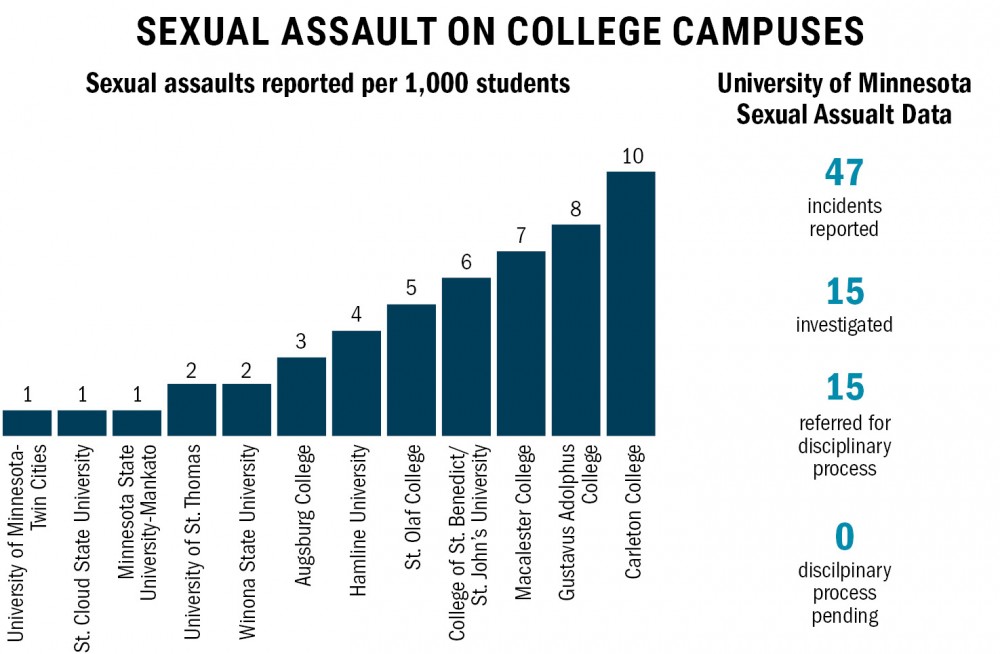

Sexual assault reporting rates were relatively low at the University, where about one incident was reported per 1,000 students.

At Carleton College, about 10 reports were filed per 1,000 students. About eight assaults were reported per 1,000 students at Gustavus Adolphus College. Both campuses have recently been criticized for allegedly mishandling sexual assault reports — an increasingly common occurrence nationwide.

Additionally, Palmer said the fact that the numbers of internal investigations and disciplinary proceedings are equal at some schools — like the University where there were 15 of each — is an encouraging sign.

“That shows to me that some thorough investigations are happening and that the school is taking it seriously,” Palmer said.

It’s unclear from the state’s report how many accused students were found responsible — though it’s less than 10 — for sexual assault at the University.

Less than one-fifth of the reported incidents were reported to law enforcement statewide according to the report, and about one-third were referred for disciplinary processes.

There are several reasons only 15 investigations were conducted at the University, said Tina Marisam, assistant director of the University’s Office for Equal Opportunity and Affirmative Action, which handles sexual misconduct investigations at the school.

If the accused person isn’t a University student, staff or faculty, they don’t have jurisdiction and can’t pursue the case, she said. Sometimes reporting students don’t want an investigation to take place, Marisam said.

“We would like to investigate all sexual misconduct reports, however, we follow the federal guidance that tells us we shouldn’t investigate unless the impacted student wants that to happen,” she said.

University investigations and police investigations are separate processes, she said, and students might choose not to start a police investigation either.

Further, the criminal process tends to be longer and have a higher burden of proof than University investigations, which can deter victims, she said.

To find a student responsible of sexual assault, the University uses a federally-required “more likely than not” preponderance of evidence standard, while criminal courts use the higher “beyond a reasonable doubt” standard.

Students’ decisions to not pursue investigation after reporting sexual misconduct should be researched further, Palmer, the MNCASA spokeswoman, said.

“It’s worth looking into the reasons behind that to see if there’s something about the way they were received that was a problem,” she said.