From now until July 23, the University of Minnesota’s Weisman Art Museum will host an exhibit, “Dear Darwin,” focused on how art and science interact.

The name comes from the process the artists took in creating their work. Most of the art is accompanied by a letter written to evolutionary biologist Charles Darwin.

“Each artist wrote a musing letter to Darwin,” curator Diane Mullin said. “About how they were inspired to make their pieces and why they were working on those subjects.”

“Dear Darwin” falls outside the typical purview of an art museum. For many people, science and art seem antithetical to one another.

“There are two reasons as to why science and art mesh well together,” Mullin said. “First, we recognize that most people are just interested in the intersection of the two. The audience likes it. Secondly, art and science are often seen as diametrically opposite, but eventually reveal themselves to be more alike than you initially think.”

Featured artist Vesna Kittelson has a foot in both doors. Her husband is an engineer and her social circle is often populated by those interested in science.

Kittelson, who splits her time between Cambridge, England and Minneapolis, found herself in England on the 200th anniversary of Darwin’s birth. Using this moment as a backdrop, she quickly went to work studying his life, looking at his writings for inspiration.

“While I am not a scientist, I have been thinking a lot about what I can do as an artist to make a statement about protecting the environment more than we are,” Kittelson said. And since I arrived [in England] at such a key time when people were celebrating his work, I started to learn about him.”

Kittelson’s work is different because it focuses on Darwin’s personal life. Inspired by letters written between Darwin and his wife, Kittelson’s goal was to create a compelling recollection of other people that existed in Darwin’s orbit.

“I learned about his relationship with his wife Emma,” Kittelson said. “It was loving and full of sacrifices. It’s a great measure of what a wonderful relationship can be. So, I thought, ‘What can I do to celebrate their love?’”

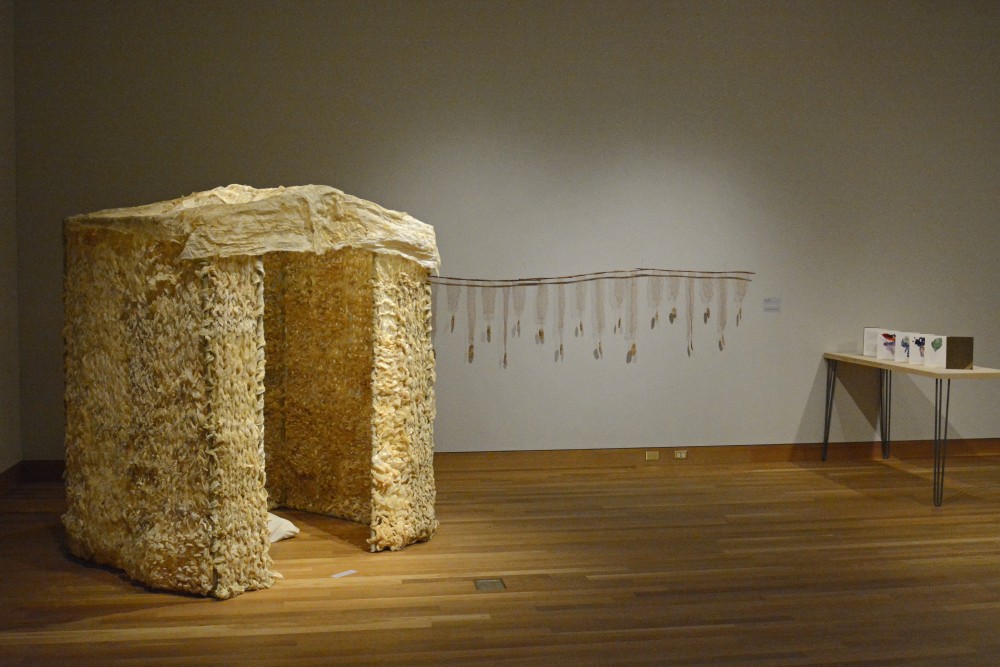

Kittelson took the idea of Darwin’s infamous intellectual walks through his garden and expanded it. She decided to invent a garden with fake plants and flowers as a visual representation of Darwin’s irascible nature.

She presented it as a gift in Emma’s memory.

Another artist, Julia Randall, took a different approach to the scientific theme.

Instead of focusing on Darwin himself, Randall focused on biology and the artistic notions behind anatomy.

Randall’s work included colored pencil drawings of lips, mouths and other body parts.

Since these drawings are oversexualized and fantastical, her work focused on the conclusions and implications you can draw from Darwin’s theories on evolution and how they affect the erotic.

Science and modern art mix together well, even if it seems counterintuitive. “Dear Darwin” is all about the ways this mixture can happen.

“It’s about shining a light on how art and science are not diametrically opposed,” Mullin said. “It’s understanding that drawing is a scientific receipt of something you’ve seen visually. Basically, picking images based on observation goes back a long way.”