University of Minnesota presidential finalist Joan Gabel was the only front-runner willing to be publicly named, even if other finalists remained in the running. That decision ended up placing Gabel on track to become the University’s 17th president.

However, there are lingering concerns about how the Board of Regents selected Gabel as the lone finalist for the position. Some transparency advocates and critics say regents “violated the spirit” of public data and open meeting laws by publicly naming only one person.

Under the Minnesota Data Practices Act, candidates’ identities are not public until they are named finalists for the position. In the University’s presidential search, a candidate is considered a finalist after the board decides to interview them. If selected as a finalist, the candidate’s name becomes public.

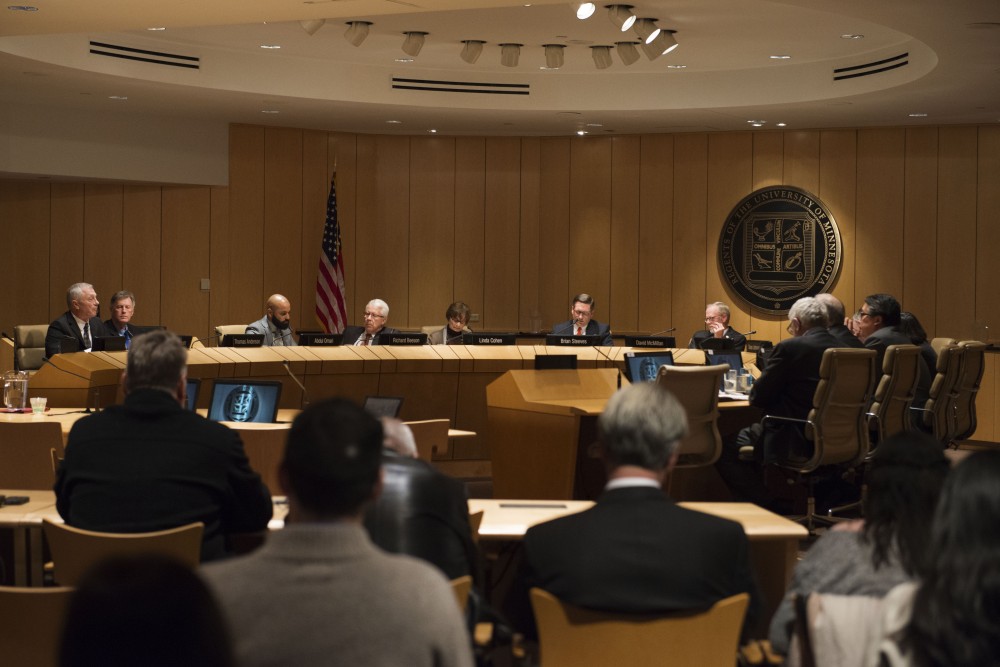

Regents voted on naming finalists at a special meeting last Wednesday. Throughout the meeting, regents did not identify the three semi-finalists, referring to them as “Candidate A,” “Candidate B” and “Candidate C.”

Unlike Gabel — revealed after the meeting as “Candidate A” — the other two candidates asked not to be publicly named unless they were selected as the sole finalist.

This created difficulties for regents. Many University members wanted multiple finalists, but regents couldn’t select Gabel and other finalists without exposing their identities.

In the end, a near-unanimous board voted to name Gabel as the sole finalist, with several regents praising her willingness to go public. The identities of the other two candidates were not made public because they were not named finalists.

Marshall Tanick, a Twin Cities constitutional attorney who advocated for the University to name multiple finalists, criticized the process for lacking transparency. He said regents “tip-toed” the boundaries of public data laws.

“I don’t know if it’s a per se violation, but it comes very close,” Tanick said of the meeting. “I think they’re trying to do everything they can to circumvent the law.”

Regent Chair David McMillan highlighted the “delicate balance” between transparency and maintaining the candidates’ confidentiality several times at the meeting, emphasizing that the board complied with the law.

In an emailed statement to the Minnesota Daily, the board office said, “The Board of Regents has conducted its search for the University’s next President with a focus on being transparent and inclusive and, at all times, in compliance with the law.”

“It is the Data Practices Act, not the board, that dictates what information is private, including the names of candidates not selected by the board as finalists,” the statement said.

Jane Kirtley, a University professor of media ethics and law, said the board’s actions do not match the spirit of the law, even though they likely complied with the law.

She took issue with the way a small group of regents met with semi-finalists, seemingly in an effort to avoid open meeting laws.

The Minnesota Open Meeting Law requires that governmental meetings, like the regent meetings, are generally open to the public. The law says a meeting is public when at least a quorum of a governmental body is gathered “whether or not action is taken or contemplated.”

Five regents met the semi-finalists in-person before the board’s meeting, a low enough number that it did not meet quorum nor require the meetings to be public.

“They did this decision … so they could avoid open meeting requirements by having only a small subset of the regents doing these interviews,” Kirtley said.

Regent Vice Chair Ken Powell, McMillan and three regents on the presidential search committee met candidates before selecting Gabel.

Several regents raised concerns that a majority of the regents did not interview front-runners before selecting a finalist.

“Being able to just talk to one really gives me concerns,” said Regent Randy Simonson.

Regent Darrin Rosha, the only vote against selecting Gabel, said that choosing a sole finalist put the University “at great peril.”

“I have very strong concerns about a process where the board should be conducting public interviews of finalists,” he said.

Several regents took issue with public data laws, including Regent Richard Beeson, who said parts of the opening meeting law do not work for the presidential search process.

“We can’t expect people who are at the most critical stages of their career to necessarily be willing to be [publicly interviewed] in a multiple candidate format,” he said.

The University has a shaky history of naming presidential finalists, including a 2004 Minnesota Supreme Court ruling that found the University violated state law by interviewing finalists in private.

Kirtley said the University is skirting its responsibility to conduct a transparent search for its next leader.

“I think they are quite adept at basically finding loopholes or cleaving to the letter of law without the spirit of the law,” she said. “They do not seem to have embraced the idea that this should be an open and transparent process.”

Kirtley did, however, commend Gabel for being willing to be publicly named.

Gabel was asked about that decision Monday after being named as the lone finalist.

“I do believe in the transparency of the process,” she said at a press conference. “I wanted to make myself available to the various constituencies across the state.”