âÄúThe Devil NotebooksâÄù Author: Laurence Rickels Publisher: University of Minnesota Press Pages: 392 Price: $24.95 Laurence A. Rickels, a professor of German and comparative literature at University of California, Santa Barbara, is a Satanist. Now, it’s not what you’re thinking; he doesn’t wear too much eye makeup or attend ritual animal sacrifices. He has, however, recently authored a book, âÄúThe Devil Notebooks,âÄù printed by the University of Minnesota Press, based on notes he has taken to give lectures on Satanism. His work is largely an essay that integrates schools of philosophical thought, pop culture, rhetoric essays and past news stories. The book recruits these sources as a means to identify the âÄúDevilâÄù as it is perceived in modern times. Rickels says that instead of an actual being, the devil exists today as both an external source of pressure and an internal transcendence above what he calls âÄúRight-Hand Rule,âÄù the oppression of self using religious guilt. He promotes rising above inhibitions and freeing yourself from shame. He goes further to imply that there are always âÄúsignsâÄù that people have chosen to succumb to the left hand. Rickels points out that parental problems pave a path toward demonic tendencies. For example, Aleister Crowley , a British occultist, displayed an odd respect for his father, who died young, and a strange detachment from his mother. Though his points sport valid evidence and his writing is obviously drawn from a pool of knowledge, something is lost in transfer. At times, it seems as though Rickels overcomplicates for the sake of complexities, intricately weaving gymnastic sentences with a mix of ill-defined pronouns, clauses and psychological terms. There are sentences that read like theyâÄôre straight from an intricate Foucault essay from a cultural studies class. Many of RickelsâÄô references are difficult to unveil, and the book seems most suited to those that have done a few preliminary readings of Freud and Nietzsche for familiarity with extreme parental complexes and ideas of the âÄúother.âÄù The pop culture employed by each âÄúnotebookâÄù will often be missed by younger generations, and so will his point. When the examples are more popular movies, like the original version of âÄúThe Stepford Wives,âÄù or famous news stories, points come across well. With one citation per page in a 400-page book, it wears thin quickly. The main problem with this book is what will also incite many to read it. âÄúThe Devil NotebooksâÄù isn’t for a leisurely read while you sip on that strawberry Jamba Juice between classes. Since it draws solely from Rickels’ experience as a professor, it reads too much like a textbook, and its convoluted philosophy references will alienate most during the first few pages.

Image by Ashley Goetz

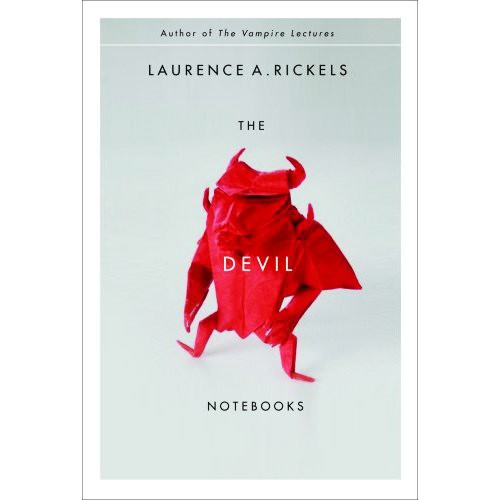

Photo courtesy University of Minnesota Press

This book is hell

Published September 18, 2008

0