Little has changed in the wake of the largest nurses’ strike in U.S. history.

Just four days after 12,000 metro area nurses walked away from their hospitals for one day, the Minnesota Nurses

Association announced it will hold a vote Monday to authorize a second, longer strike.

Despite his insistence that the one-day strike was a success, MNA spokesman John Nemo said nurses feel the threat of an indefinite strike is “the last tool in the toolbox” that could force the hospitals to negotiate.

“We’re no closer [to reaching an agreement] than we were three-plus months ago,” he said.

This open-ended strike would require 66 percent of nurses to vote in favor. If the vote passes, they must again give hospitals 10 days notice of intent to strike.

More than 90 percent of nurses voted to authorize the first strike when they gathered May 19.

With the possibility of another strike looming, both sides continue to blame the other for a contract negotiation process that has been stagnant since it began in March.

“The union continues to seek conflict and controversy rather than negotiation,” said Maureen Schriner, spokeswoman for the six hospital systems involved in contract negotiations.

Nurses from each hospital system will be meeting throughout the week to discuss the possibility of another strike.

7 a.m. Thursday to 7 a.m. Friday

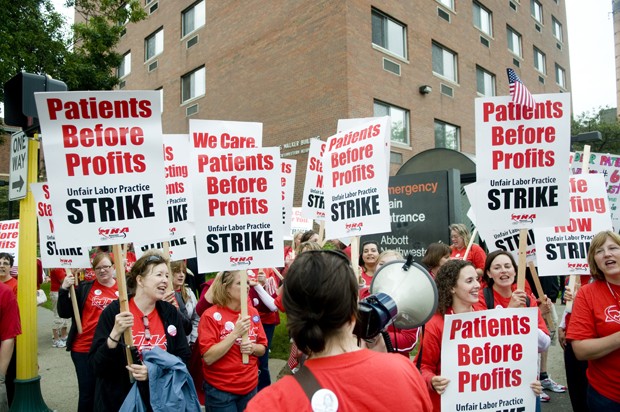

A light drizzle did nothing to dampen the enthusiasm of 12,000 nurses outside of their hospitals June 10.

Chants demanding safer staffing levels were frequently punctuated by honking from passing cars outside of Abbot Northwestern, Children’s Hospital and Phillips Eye Institute in Minneapolis. More than 2,000 nurses gathered outside the picket lines of the three hospitals.

“It feels good that we have this kind of solidarity, but it is really sad to think that the employer actually pushed us to this point,” Nellie Munn, a nurse and member of the MNA negotiating team, said outside of Children’s Hospital during the strike.

MNA has emphasized the importance of adequate staffing levels since negotiations for a new contract began in March.

Hospitals proposed that a head nurse on each floor should be responsible for deciding how many nurses are needed.

But nurses say a more permanent nurse-to-patient ratio is necessary to improve quality of care.

“The hospital said their policies are adequate for staffing. They are not,” said Kevin Campbell, a detox nurse at the Riverside campus of the University of Minnesota Medical Center, Fairview, where a smaller but equally energetic crowd of nurses walked up and down

Riverside Avenue.

Nurses have also proposed a 3.5 to 4 percent pay raise for each year of their three-year contract. Hospitals countered with a proposed 1 and 2 percent raise in the second and third years.

After giving hospitals notice of their intent to strike May 28, both sides were confident they could reach an agreement before the scheduled strike.

Two bargaining sessions with a federal mediator took place June 2 and 4, but little progress was made. Both nurses and hospitals announced they failed to compromise shortly after the second session, and made no plans to try again before the strike.

Nemo called those sessions “an exercise in futility.”

The six hospital systems involved in contract negotiations began preparing for a possible strike more than a month ago, Schriner said.

By hiring 2,800 temporary replacement nurses, sending some patients to hospitals not affected by the strike and reducing patient volume, hospitals were able to cope with the walkout and still provide quality care, Schriner said.

The 14 hospitals told their nurses to wait for a phone call before returning to work. Nurses at Fairview–Riverside said Thursday they had been given the go-ahead to return on Friday morning.

As of press time, 200 nurses had still not been called to return to Abbott Northwestern Children’s Hospital in St. Paul and United Hospital, MNA said.