Though the Deepwater Horizon oil leak happened 1,500 miles away and 5,000 feet under water, a team of University of Minnesota engineering students is contributing to the cleanup.

The College of Science and Engineering team has created a high-speed submersible 3-D holographic camera that determines if microorganisms are eating away at oil droplets in the sea.

“BP claims there is no more oil on the surface, so definitely there are some microorganisms that eat them,” Yan Ming Tan , a fourth-year aerospace engineering student who is part of the CSE team, said. “We just donâÄôt know which microorganisms.”

The discovery of microorganisms consuming oil droplets would be monumental in dealing with oil spills in the future, as it would mean scientists could use them in place of chemical dispersants, Tan said.

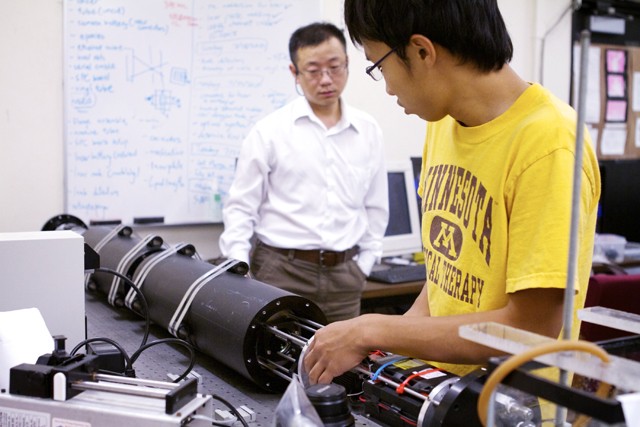

The team, consisting of CSE professor Jian Sheng and three students, brought the instrument, called the HoloSub, to the Marine Science Institute at the University of Texas, where they were able to make initial test runs.

The camera and the research were sponsored by a $645,000 National Science Foundation grant awarded to the University of Minnesota. The proposal that was initially awarded the grant money, however, changed direction in response to the BP oil spill April in the Gulf of Mexico.

In the spring, when Sheng and his team applied for the NSF grant, the purpose of the high-speed camera was to better understand the flow fields around coral reef regions and how fish react to these fields. This idea has since taken a backseat.

Sheng is applying for a new grant that will also allow them to use the camera to research the red tide phenomenon, also known as an algal bloom, which affects many coastal cities.

Red tides are large concentrations of naturally occurring microorganisms that release toxins harmful to humans respiratory systems and can stretch up to several miles.

With a camera that is capable of taking photos at 6,000 frames per second and a powerful laser, the instrument is one of a kind, Sheng said.

Weighing close to 100 pounds, all that is needed to operate the instrument is enough muscle to drop it in the water, he said.

The group took a weeklong trip to the Gulf oil spill region in early September, but due to a broken lens, was unable to actually deploy the camera, said Zhen John Goo, a third-year aerospace engineering student who went on the trip.

The team has plans to return to the region in the future.

“In the field, [it] is so different from the lab,” John Goo said. “We encountered small problems here and there.”

Back in Akerman Hall , the instrument is going through several additions including allowing the instrument operators to turn the camera on wirelessly. Currently, a switch must be flipped on manually in the water, Tan said.