Megan Schmidt didn’t plan to join the University of Minnesota’s Visible Heart Lab, but once she began work there as part of her Ph.D. program, she was sold.

“I would basically do any sort of research to be in this lab,” Schmidt says.

The lab, which Schmidt describes as friendly and collaborative, has contributed to cutting-edge medical projects since its start in 1997. Earlier this year, principal investigator and leader Dr. Paul Iaizzo and a team of his researchers 3-D-printed a heart replica, which was used for a surgeon team’s practice before a complicated surgery.

“I have one of the coolest jobs on the planet. … You get motivated because you can help a lot of people,” Iaizzo said.

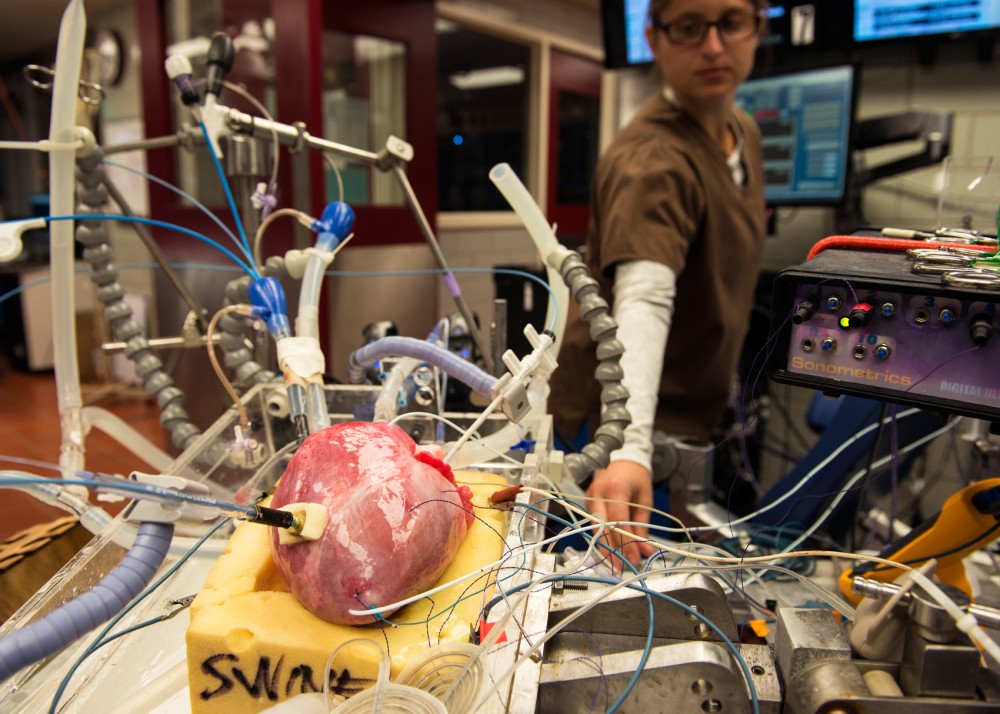

The lab focuses on isolated hearts of large animals. Iaizzo and his team can rig up an animal heart — keeping it alive for several hours — and study its live functions — something no other lab in the world regularly does, Iaizzo said.

About 45 researchers — ranging from undergraduates to Ph.D.s — collaborate on individual research projects, Schmidt said. Iaizzo regularly plays music in the lab, and researchers joke that if country music comes on, the reanimated pig heart will die, Schmidt said.

When she started, Schmidt only knew basic high school anatomy, but now she researches the heart’s electrophysiology. The sociable nature of the lab — where everyone goes by their first name — drew her in, Schmidt said.

“I tried to call him Dr. Iaizzo for about a month,” she said. “Then I just gave up.”

Earlier this year, the lab used their 3-D replicas in a clinical setting for the first time, something Iaizzo said may become more common in the future.

When a patient needed a new aortic valve, the surgery team had hesitations about the intricate procedure. Iaizzo and his team 3-D-printed a replica of the patient’s heart, allowing the surgeons to study the heart and determine what device the patient needed.

“It just helps; it’s another way to have it right there in your hand,” Iaizzo said. “I think it really helped the clinical team gain confidence in what device they were gonna use, and some confidence to proceed with the procedure,” he said.

The lab began 3-D-printing models three years ago, Iaizzo said.

“Basically we’ve been taking the hearts and scanning them to make images, and then we can create the digital models,” he said. “Once you’ve created the digital models, you might as well try and print ’em.”

JingJing Zhu, an undergraduate student in the lab, said an experienced researcher can complete the 3-D scanning and preparation for a 3-D-printed heart in 24 hours, but first tries can often take months.

The lab has printed hundreds of models, Iaizzo said, allowing doctors to study hearts that are larger in scale.

“[The doctor] can have a better perspective and study all the nuances of that anatomy,” he said.

Iaizzo invited his brother-in-law, Mark Hjelle — an engineer at Medtronic — to see the work he had been doing on guinea pig hearts in 1997.

“They said ‘that’s cool,’ but we should be able to do that with large, mammalian hearts,” Iaizzo said.

From there a partnership with Medtronic began; the medical techonology company now supports the lab through research contracts.

Iaizzo said working with students is one of the main highlights of his time at the lab.

“It’s the fun part about the job; it’s really working with the young mind and talent that keeps things moving forward,” he said.

For Megan Schmidt, it’s Iaizzo collaborative spirit that keeps her motivated.

“I can ask Paul anything, anytime,” she said. “He’s all about getting his students to succeeed in what he’s trying to do.”