Craig Packer had his first encounter with Africa while studying baboons in Tanzania when he was an undergraduate in the late ’60s and early ’70s.

And after a yearlong study of primates in Japan, he returned to head a lion research project in Serengeti National Park in 1978.

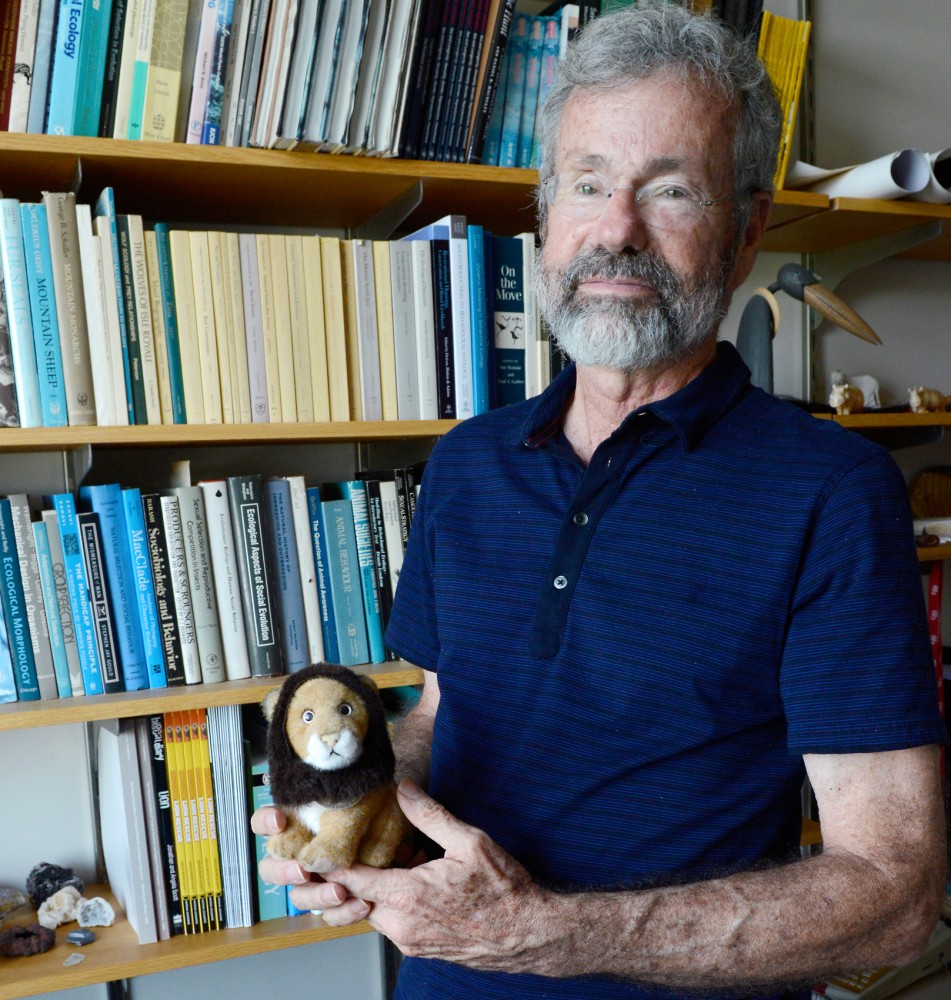

Packer is now the director of the University of Minnesota’s Lion Research Center and spends much of his time in South Africa, thousands of miles from his St. Paul office.

A professor in the Department of Ecology, Evolution and Behavior, Packer just released his second book and will give a talk about it on Wednesday at Coffman Union.

The book, “Lions in the Balance,” delves into his experiences living in South Africa and his journey as a scientist.

Packer began studying behavioral ecology in primates with Jane Goodall while he was an undergraduate at Stanford University.

After returning from his study in Japan, he was looking for a new project. Some of his friends were studying the lions in Serengeti National Park, and he took the lead on the project.

At that point, the lions had already been observed for 12 years, which was important to his research because it provided information about lion family structure.

“For a lot of the ideas in cooperative behavior, knowing that family structure is essential because, as in humans, we kind of expect sisters to behave differently to each other than any two females in the class,” Packer said.

Packer was recently banned from Tanzania and had to relocate his research to South Africa.

“They didn’t want me there because I was trying to reform their hunting industry,” he said.

Much of Packer’s work is focused around a project called Snapshot Serengeti, which was started by a former graduate student in 2010.

The faculty- and student-run project is composed of more than 200 camera traps set up across 1,125 square kilometers in Serengeti National Park.

Using heat and motion sensors, the cameras have collected millions of high-resolution photographs of lions. The images will be used for data analysis at the University.

Meredith Palmer, an ecology, evolution and behavior doctoral student, has been working on Snapshot Serengeti with Packer for the past two years, managing camera traps and analyzing data.

Palmer said Packer is one of the field’s leading experts on Serengeti lions because of the amount of work he puts into the project.

She and Packer are working to expand Snapshot into South Africa as their latest addition to the project, she said.

Michael Anderson, a professor in the Department of Biology at Wake Forest University, has also worked closely with Packer on the Serengeti project.

In the past several years, Anderson has been conducting environmental research in Tanzania, sampling plant species and looking at how soil, rainfall and fire affect the landscapes.

Anderson said although he had been working in the Serengeti for a while, he didn’t get to know Packer because they worked in different fields.

When Packer reached out to Anderson to collaborate a few years ago, he joined the project by helping analyze environmental factors that might affect the lion research, such as the types of plants that grow in front of the various camera traps.

“Right away I liked [Packer] because of his insight into many different issues surrounding savannahs and savannah ecology,” Anderson said.

He said he was impressed because of Packer’s knowledge on a variety of subjects, surrounding behavioral ecology, including human impact — something not always typical of lion researchers.

When approaching large mammal projects, most scientists look through the lens of behavioral ecology and observation, which Packer does, Anderson said, but he takes it a step further.

“He actually tests theories through experimentation in ways that are very creative that I just find really impressive,” he said.