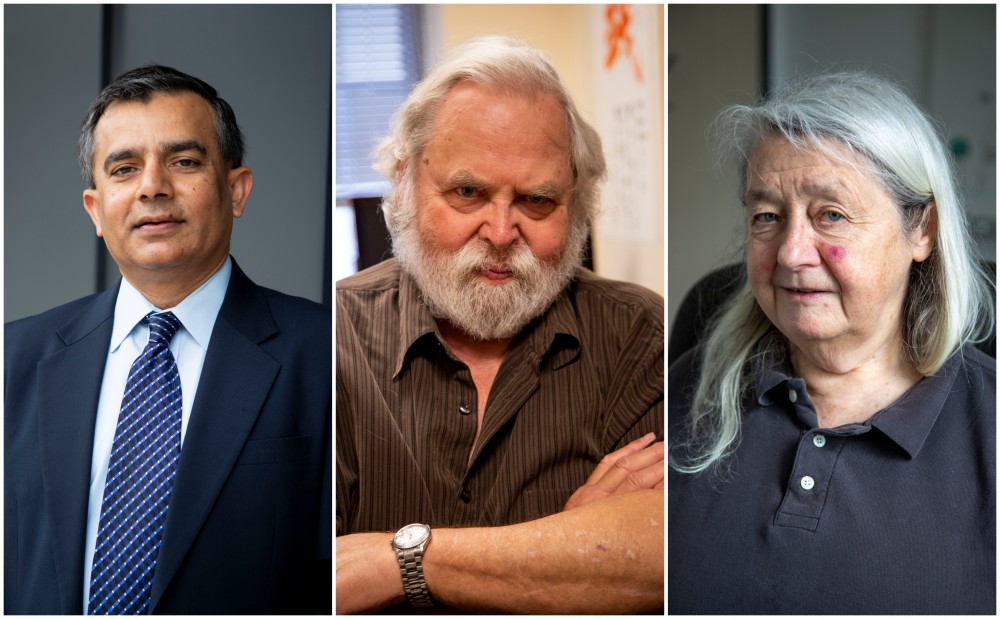

The legacy professors: those who have worked at the University for decades on end. Through years of work, their names have become synonymous with innovation. They are a group of authors, researchers, scientists, friends and mentors, their stories as varied as their respective backgrounds and life experiences. These are the individuals who have both witnessed history and become a part of it.

From tear gas to tenure

The role of the journalist is to act as a record keeper for history. Kenneth Doyle, a professor at the Hubbard School of Journalism and Mass Communication, has done just that since joining the University in September 1966.

“I think life today at the University is much more boring than in the past,” Doyle said with a light chuckle.

Doyle has lived through things most students can only experience through black and white photos printed in history books. He can remember watching Vietnam War protests from an upper floor of Ford Hall.

Students had barricaded Washington Avenue and were met with soldiers and police officers with batons.

“It really was like a war zone,” Doyle said. “They were throwing tear gas across the mall. Helicopters were flying overhead and the ‘pud, pud, pud’ sounds of the blades made the adrenaline surge.”

Doyle has noted a distinct shift in student life since his own college days, when he and his friends would “commandeer” tables at a nearby coffee shop and “talk on end about philosophy and theology.”

Now, he said the world is too hurried to do that; with the expense of college tuition, students may work multiple jobs and lack the luxury of time for contemplation. More than that, Doyle misses a culture that encourages discussion.

“It is much harder recently for students to discuss controversial issues. You can’t run a university on the belief of not offending people, you must believe that a university is the marketplace of ideas,” he said.

In the more than 50 years that he has been at the University, Doyle said he enjoys the relationships he has built with students and the chance to be a mentor the most.

“[Now], I think students may view me less as a fatherly figure and more of a grandfather,” he said.

A field all her own

When she started at the University in 1979 to teach and research the effects of early childhood adversity, Dr. Megan Gunnar still used a typewriter. Things have changed a bit since then.

In the following four decades, Gunnar has taught, researched, mentored, raised a family and helped found an institute which bears her name: the Gunnar Laboratory for Developmental Psychobiology Research. Though she admits it was hard work, Gunnar credits her success in large part to her colleagues.

“It’s a fabulous department and a wonderful place to be. There’s a lot to be said for a supportive, cohesive department with great people who care about what they’re doing,” Gunnar said.

Graduate student Carrie DePasquale, who currently researches in the Gunnar Lab, said she also feels thankful for the chance to work with Gunnar.

“The way that [Gunnar] thinks through problems and … helps me through my research is really helpful,” DePasquale said. “When I was looking at graduate schools, I looked at a bunch of other professors only to realize that the educators I liked had all been mentored by Megan.”

Gunnar said the opportunities for guidance and mentorship have proven most gratifying to her.

“I had no idea when I started teaching how much I would truly, truly enjoy mentoring,” Gunnar said. “My legacy? I think it will be all those brilliant students out there changing the world.”

Expansion and innovation

Dr. Shashi Shekhar came to the University around Christmas 1989. It was the same year that the Berlin Wall fell, a time when shoulder pads were almost as large as the hair.

Shekhar had just received his doctorate in computer science from Berkeley. Over the following decades, he watched his field grow beyond belief. Students now have computers that fit in their pockets; in 1989, the newly introduced Macintosh portable computer weighed in at 16 pounds.

Since coming to the University, Shekhar has worked with the U.S. government and NASA. He literally wrote the book on spatial data: “There were no books, so I figured I’d be the one to write one,” he said.

His field grew rapidly after the expansion of the internet, Shekhar said. His name quickly became synonymous with research and innovation to his colleagues.

“Shekhar is a researcher who can easily see how the algorithms and mathematical proofs he develops can be applied to real-world engineering problems,” said William Northrop, an associate professor at the University who has collaborated with Shekhar since 2014. “He has changed my outlook on the field of computer science.”

Yet in his 30 years in the field, engineering problems are not the only ones Shekhar has fought to address. For years, he has advocated to lessen disparities, especially gender and racial, among the computer science field.

“If we look at some of the underrepresented minorities, very few are in computer science,” he said.

Though there is still more to be done, Shekhar said he’s blown away by the progress, both socially and technologically, in the past 30 years.

“In your lifetime, you see those ideas and technologies you’ve worked on become very prevalent in society,” Shekhar said. “How amazing is that?”

‘Family style’

“We met at Stanford. I was a student, she was a postdoc,” said professor Dan Boley. “The rest from there is history.”

Boley came to the Twin Cities with his girlfriend, Maria Gini, in 1981. Gini, originally from Italy, studied artificial intelligence; Boley focused on data science. The two married shortly after moving. Boley got a job at the University in 1981 and Gini accepted a position in the same department at the University a year later.

“We were lucky … the department faculty was only 14 people. I interviewed and they offered me a job. That doesn’t always happen,” Gini said. “Having two jobs in the same place at the same time makes a lot of things simpler.”

The two witnessed massive changes both at the University and in their field of study. There is just more on campus, Gini said: more bureaucracy, more formality, more students, more buildings.

“The computer science department was just in the infancy of getting connected by email to the rest of the country,” Boley said. Both Boley and Gini came to the University around the advent of the internet — most students they teach now have never lived in a pre-internet world.

Neither questioned ever leaving the University or Twin Cities: the art, the greenery and the friendliness of the people helped cement their roots here. Gini said she enjoys working at a place that emphasizes research, while still offering simple life pleasures.

“If I want to look at the Mississippi, I go outside my office, go on the bridge and watch the river. You can just watch the water and think about life,” Gini said. “I love the students and faculty — it’s like family style here.”

For Boley and Gini, the secret to their legacies is simple but vital: love. For one another, for their home, for their students and for their work.

“I always hope I helped students in discovering themselves and what they wanted to do,” Gini said. “I always tell students that money is important, but if you have a job and every day you go to work and you’re happy because you’re going there, that is worth more than money. That’s what I’ve got.”