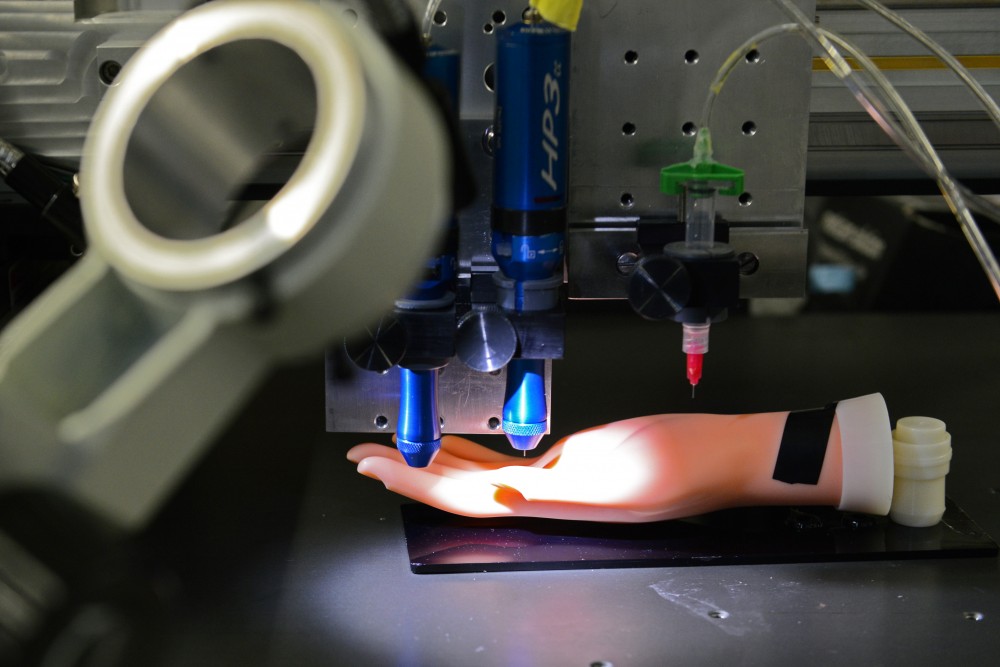

A team of University of Minnesota scientists has developed a futuristic method of 3D printing.

Michael McAlpine, associate professor of mechanical engineering at the University, and his lab created a new method of 3D printing that prints working electronics on uneven surfaces. His team believes this research could be the first step towards printing on human skin.

The research was published online in May in the academic journal “Advanced Materials.”

“We’re trying to expand the capabilities of 3D printing from hard plastic to what we call functional materials,” McAlpine said.

Printing electronic materials has a variety of possible applications, many of which are medical, he said. McAlpine foresees that surgical robots could be enhanced to send surgeons controlling them signals of what they feel using this method. Other uses could include printing sensors onto prosthetic limbs to give the wearers feeling.

“[McAlpine’s] work has really redefined the way we think about 3D printing,” said Suhasa Kodandaramaiah, assistant professor in mechanical engineering at the University. He said the added precision of touch-sensitive surgical robots could let surgeons do operations that are currently impossible.

ShuangZhuang Guo, the lead researcher on the project, a postdoctoral research associate in McAlpine’s lab, said this new electronics printing method is cheaper and easier than current methods of creating electronics.

“Normally the electronic devices should be fabricated in clean rooms, it’s very complex and very expensive,” he said.But before developing this method, the team faced several challenges. Across two years, they built a brand new printer, developed new types of inks and found ways to print on uneven surfaces.

Guo said to print on uneven surfaces, they created a 3D printer able to read scans of the objects beforehand.

In the future, the lab hopes to print on human skin, but many obstacles still stand in the way.

McAlpine said 3D printers’ needles are too painfully sharp for human skin, and even minor movements — what Guo calls “microscale movements” — can cause issues in current methods of 3D printing.

But the team is working on solving these too.

“We’re actually developing computer vision controls that track small motions like that and adjust the printer so it tracks them,” McAlpine said.

Once they can print on skin, he said soldiers in the battlefield could have toxic chemical scanners or, in a distant future, cell phones built into their arms.

“It’s very hard to realize devices that conform to the actual shape of the skin without this kind of technology that [McAlpine’s] lab has developed,” Kodandaramaiah said.