A University of Minnesota researcher has made a major discovery about the mutation of Middle East respiratory syndrome, a potentially life-threatening respiratory illness that causes fever and difficulty breathing.

MERS has infected hundreds in South Korea in recent weeks and is responsible for 27 deaths, according to the World Health Organization. And University research published this month may soon provide some answers about the disease’s origins and how it is transmitted to humans.

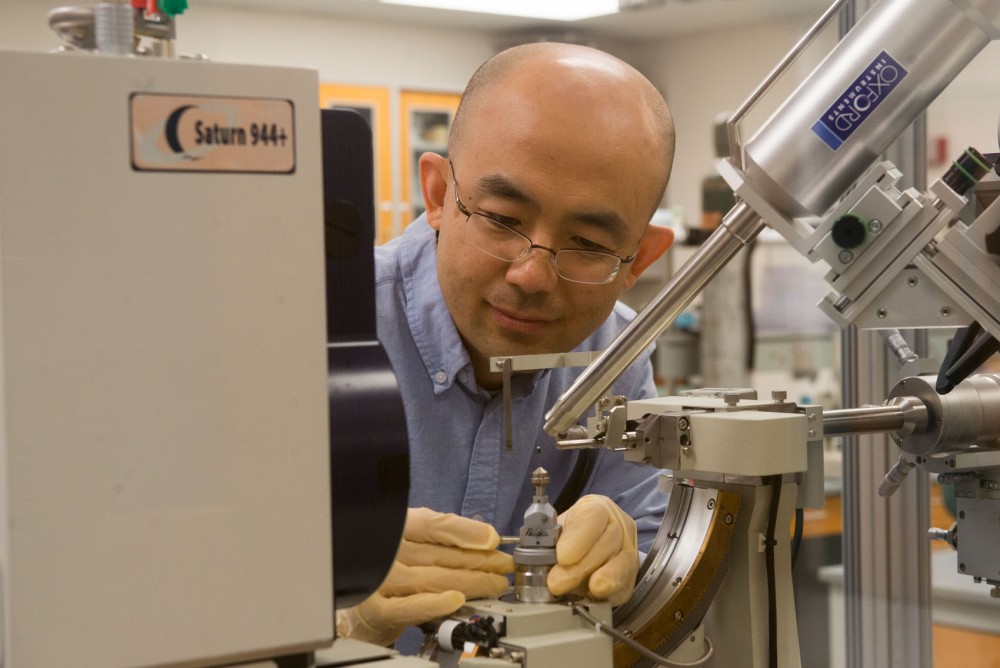

The research, spearheaded by pharmacology professor Fang Li, found two critical mutations in a virus similar to MERS in bats. His findings may reveal how the virus can easily mutate and subsequently affect humans.

Li said his findings are an important first step in understanding the origin of the virus and preventing animal-to-human transmission.

“A lot of emerging infectious diseases come from animals, so it’s critical for us to understand how these pathogens transmit from animals to humans,” Li said.

Li’s previous work focused on mutations in severe acute respiratory syndrome, a relative of MERS, which was responsible for infecting more than 8,000 people in an

outbreak between 2002 and 2003, according WHO.

SARS is believed to originate from bats and has a lower fatality rate than MERS. Thirty-six percent of people infected with MERS die, but Li said the virus jumps between humans slower than SARS.

According to the U.S. Agency for International Development, almost 75 percent of emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic, meaning they were transmitted from wildlife before spreading between humans.

“The biggest challenge is that we frequently don’t always know the disease pathogenesis and transmission routes of diseases,” associate professor of veterinarian and biomedical sciences Pamela Skinner said, adding that certain diseases transmitted by animals can be deadlier when the virus spreads to humans.

The origin of MERS still remains unclear. Camels are believed to have contracted the disease from bats, and the disease was then likely passed on to humans, according to WHO.

“If we know a virus jumps from a specific animal to humans, we can reduce contact and monitor the virus’ evolution,” Li said, noting his research supports the idea that the virus originated in bats.

Associate professor Bob Geraghty at the Center for Drug Design said he worries foreign hospitals may not be prepared to handle certain outbreaks, especially MERS, which was first reported in the Middle East.

“As these viruses emerge, we’re going to have to have a good protocol for how we can identify who comes down with a virus, where we send them and how they’re treated,” Geraghty said.

Minnesota hospitals and health care facilities are being told to watch for signs of the virus.

On June 12, the Minnesota Department of Health issued a list of recommendations and information for health care providers highlighting details about the virus,

including symptoms and steps that should be taken to identify the virus.

An International Health Regulations emergency committee noted that a lack of health care worker awareness and poor prevention measures contributed to the virus’ spread.

“We’re trying to figure out how these things happen and why bats are the natural reservoir of these diseases,” Li said. “That’s going to be our next step.”