A University of Minnesota collaboration’s COVID-19 tracking app has data from more than 52,000 U.S. neighborhoods and aims to reduce the impact of the pandemic.

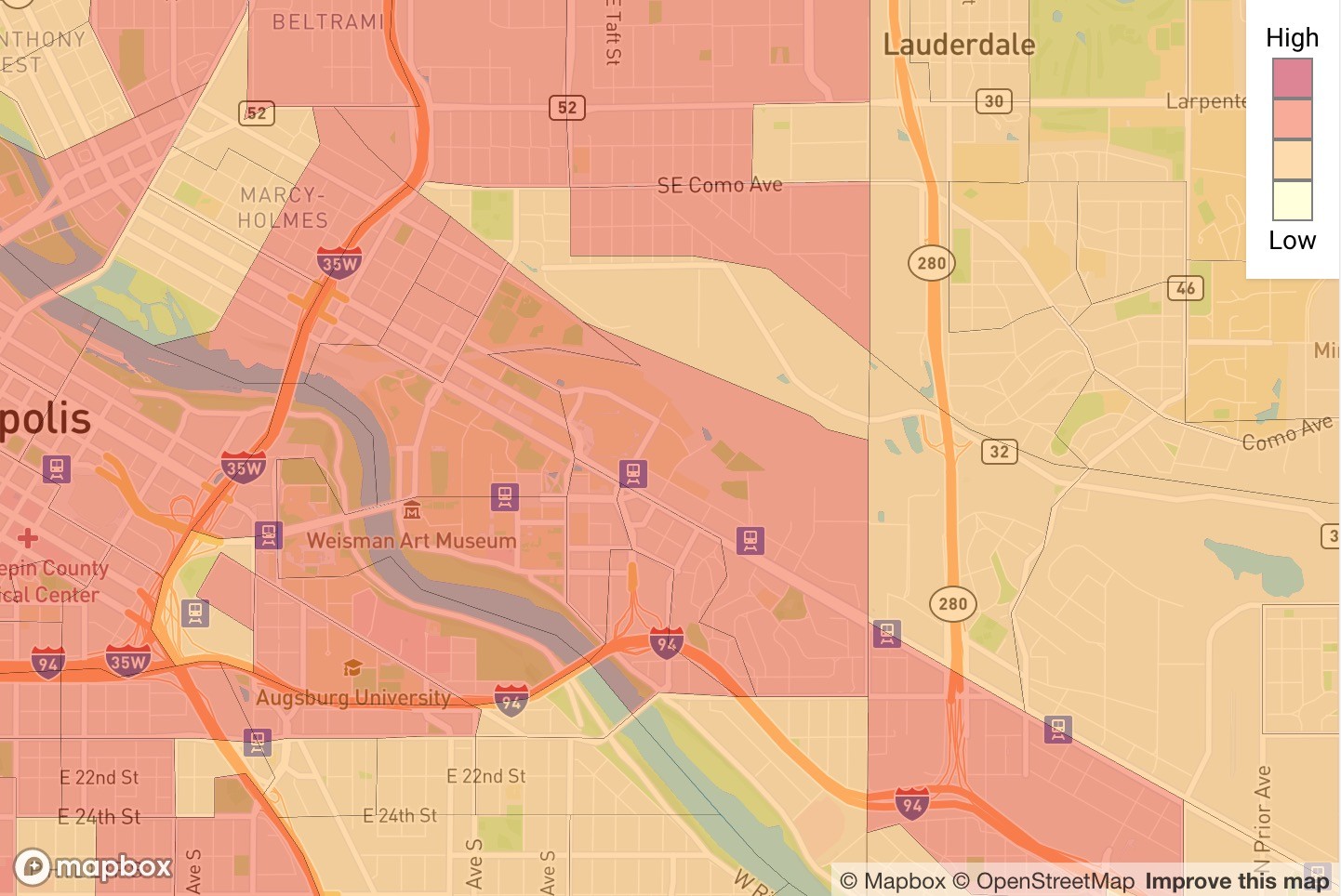

SafeDistance, launched April 22, allows users to look at COVID-19 risk areas, or where there may be many cases across the nation. Users are anonymous and can take a COVID-19 symptom survey with six tiers of recommendations. The app can track where people are moving and make predictions about where COVID-19 might be spreading.

“We’ve definitely seen people with symptoms moving around,” said Brian Krohn, an entrepreneur in residence at Modern Logic, a digital product agency.

Part of the reason for the large response to the app has to do with the fact that it is able to track location, he said. The user can view the data at the neighborhood or county level.

“We tried to set up our risk maps so they aren’t dependent on how many people use it, although that contributes to them,” said Bjorn Westgard, an emergency physician at Regions Hospital and a research investigator at HealthPartners Institute.

Creators have worked with many partners to spread word of the app, including HealthPartners, who shared it with their 26,000 employees. However, Krohn said they have not been able to get state-level support yet due to the Minnesota Department of Health being occupied with the COVID-19 response.

“As this was coming down the pipe, the hope is to help save lives, provide people with information so they can make more effective decisions and reduce the ultimate impact of COVID,” he said.

The team has also been working on figuring out the best use of the app and if there is anything else they can add.

“Our thought is that if you want to use it for things like contact tracing or for advising people who need to go back to work or students potentially thinking about going to school, you could potentially integrate all those elements into the survey and recommendation portion,” Westgard said.

Krohn said it was important for people to begin looking at data in terms of neighborhoods rather than on global or national scales. COVID-19 data from individual neighborhoods can shed light on systemic issues related to race and income.

“When you think about your neighborhood, that’s where these actual problems are, and people can actually make decisions,” he said.

While SafeDistance is successful, Westgard said no app has proven to be a game changer yet.

“If the CDC put out a tracker, that’d probably be the ultimate right thing to do,” he said.

Deondre Smiles, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Geography at The Ohio State University, said his mother, who lives and works in Minneapolis, recommended the app to him.

While Smiles said he likes the app, he wishes there was more specific county-level data. Users cannot click on counties and see how many cases are in each one.

He said it is important for him to have because he has family in rural Minnesota. With that option, he said, “We can advise them on what to do to keep themselves safe.”