A University of Minnesota study is using data and lived stories to drive a better understanding of gentrification in Minneapolis and St. Paul neighborhoods, including areas around campus.

The Center for Urban and Regional Affairs presented its study on gentrification to a Minneapolis City Council committee on July 11. The research identified gentrifying neighborhoods based on census data spanning 2000 to 2015, and further interviewed and recorded experiences of residents living in those areas.

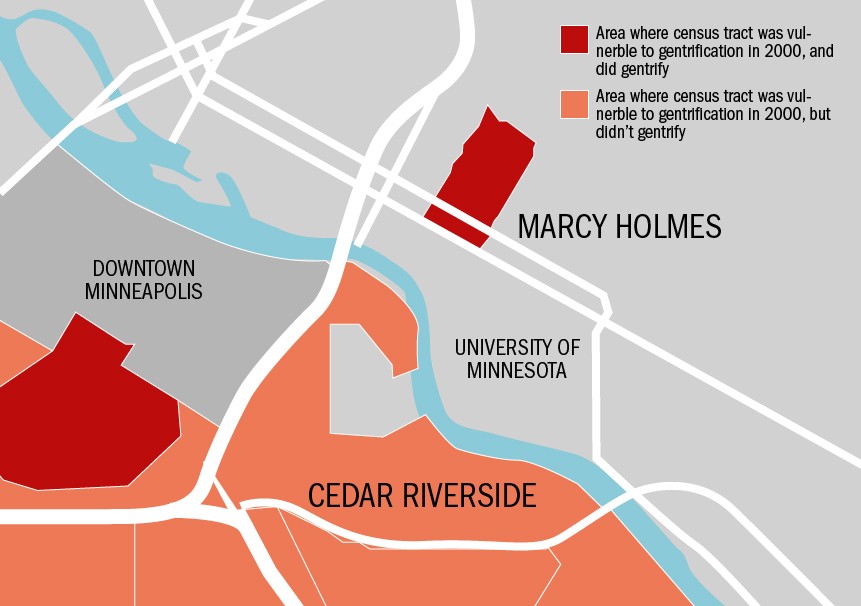

Results were mixed for University neighborhoods. A portion of Dinkytown was marked as gentrified but yielded outlier statistics. The Cedar-Riverside neighborhood was deemed “vulnerable” but did not gentrify in the 15-year time frame.

Researchers based their work on other studies of gentrification rather than developing new definitions. Tony Damiano, a lead researcher on the quantitative study, said this was to limit the impact of their own biases.

Generally, the other studies agreed that patterns of increasing median home value, rents and residents with a bachelor’s degree above city averages were indicative of a shift toward gentrification. Changes in racial demographics were not considered an indicator, although researchers tracked population shifts in indigenous groups and people of color.

“Gentrification, as it’s commonly understood, is the upgrading of previously low-income neighborhoods,” said Damiano, referring to influxes of affluent populations and high-value property.

Not all vulnerable low-income areas showed changes that were consistent with this “upgrade,” like Cedar-Riverside. The area experienced a notable rent increase, but a decline in home value and residents with bachelor’s degrees. Damiano said he doesn’t know why the West Bank neighborhood didn’t gentrify, and the qualitative study didn’t interview residents in the area.

Although the results say little about the neighborhood’s future, the present fear of gentrification is a looming concern for some Cedar-Riverside residents.

Ward 6 City Council member Abdi Warsame said the socioeconomic anxiety is centered on displacement due to rising rents and the encroachment of downtown development.

“Those who have money can move out to the suburbs, those who have education have more choice. It’s just the vulnerable older population and those who have low-income jobs who feel that they have no place in the neighborhood,” Warsame said. He added that seniors in particular fear the loss of their public housing.

On the other side of the river, a different kind of change is taking root in eastern Marcy-Holmes. The landscape is growing pricier, but that doesn’t necessarily mean resident displacement.

Researchers consider the gentrified tract of Dinkytown land to be an outlier because of drastic differences between statistics. The median home value increased by about 40 percent, but median household income decreased by about 28 percent.

Damiano attributed the discrepancies to an increase in student housing. According to a February CURA presentation, 27 apartment projects were built in the University area from 2010 to 2016.

Long-time Marcy-Holmes resident Marcus Mills said he found the study results unsurprising because Dinkytown has increasingly become an attractive place to live. But the transient student population means the low-income residents of color don’t experience displacement in the same way as other gentrified places.

“The forces that keep people of color in that area are independent of market forces,” Mills said.

He noted housing geared toward foreign exchange students, like the Chateau Student Housing Co-Op, is one way the area retains students of color.

The study signals there is more work to be done to support communities upended by gentrification, Damiano said.

“We hope that by… providing some compelling evidence that, although not happening everywhere, gentrification is happening and that it’s important for cities and local governments to be responsive to people fearful of the potential negative effects,” Damiano said.