Students are using their cellphones to do classical chemistry experiments, a technique that could save high schools thousands of dollars.

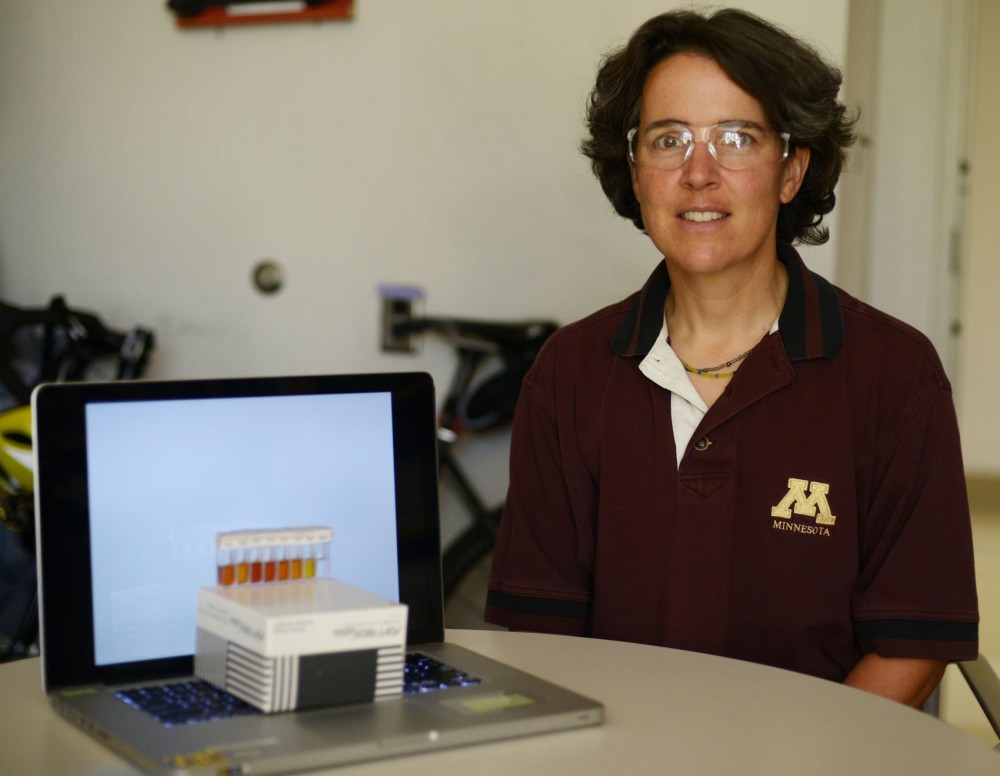

University of Minnesota alumnus Eric Kehoe and associate chemistry professor Lee Penn developed the technique to evaluate a liquid’s concentration by simply taking a photo with a smartphone.

Penn has used the technique for the past two years in her freshman honors seminar, and Kehoe, who is a chemistry teacher at Janesville-Waldorf-Pemberton High School, has used it in his classes.

“It makes it more accessible that way … taking something they’re interested in, their phones, and putting it in the classroom,” Kehoe said. “We can teach that there is more you can do with cellphones than just chatting with friends.”

In the U.S., 78 percent of 12- to 17-year-olds own a cellphone and about 37 percent own a smartphone, according to a 2013 report from the Pew Research Center.

Kehoe said most students would be able to use their own cellphone in class to analyze solutions. Those who don’t have smartphones can be paired with a student who does, or use a camera phone and do the analysis on a computer.

Pre-existing free phone or computer applications, like Color Detector, analyze the amounts of red, blue and green in the photos. The values are compared to Beer’s Law, which states the deeper a solution’s color is, the higher its concentration.

Colors are usually analyzed with a spectrometer, which can cost anywhere from $400 to $1,000.

Kehoe said it’s difficult for high schools to use spectrometers because of their cost. Even if the school can purchase one or two spectrometers, he said, it can take a while for the whole class to conduct the experiments.

“Between myself and the other science teachers, we get a little over $2,000 for a budget each year,” Kehoe said. “I would use half that for a few devices, and then I wouldn’t have money to buy anything else.”

Since spectrometers are too expensive, Kehoe experimented with cellphones to see if they could analyze the color solutions accurately. The technique worked and is accurate about 95 percent of the time, he said.

Penn said using cellphones in the classroom helps students relate to what they’re learning and makes the experiment more interesting.

“I think it’s cool how you can use camera phones, something you can use everyday, to do chemistry,” said University neuroscience freshman Nmesoma Akpati.

Biology, society and environment sophomore Hallie White said the technique was “simple and fast.”

Kehoe said analyzing color with cellphones is fun for students and can easily be done at home or anywhere outside the classroom.

“I have students looking at food coloring in frosting or mixing different shades of a paint,” Kehoe said.

Spectrometers can also be hard to use when scientists are conducting research in the field. Penn said taking a photo of water samples with a cellphone could be more efficient since data can be analyzed right away.

“Let’s say I’m doing an

environmental analysis and I’m analyzing river water,” Penn said. “All I need is my camera phone to take pictures.”

Since cellphones are less expensive than spectrometers, Penn said, it encourages more participation in experiments, breaks down the barrier for schools without resources and lets students use their own devices.

“I think that’s one thing I really like about it,” Kehoe said, “that I can turn this back to students and say, ‘Get out of the lab and bring back what you’ve learned outside.’”