Agriculture education senior Jared Luhman’s organic family farm in Goodhue, Minn., ships soil samples off to a lab once every few years to determine how much fertilizer is appropriate for the 200-acre cropland — a costly and timely process that often doesn’t deliver detailed results.

But a portable device being developed at the University of Minnesota could help with that.

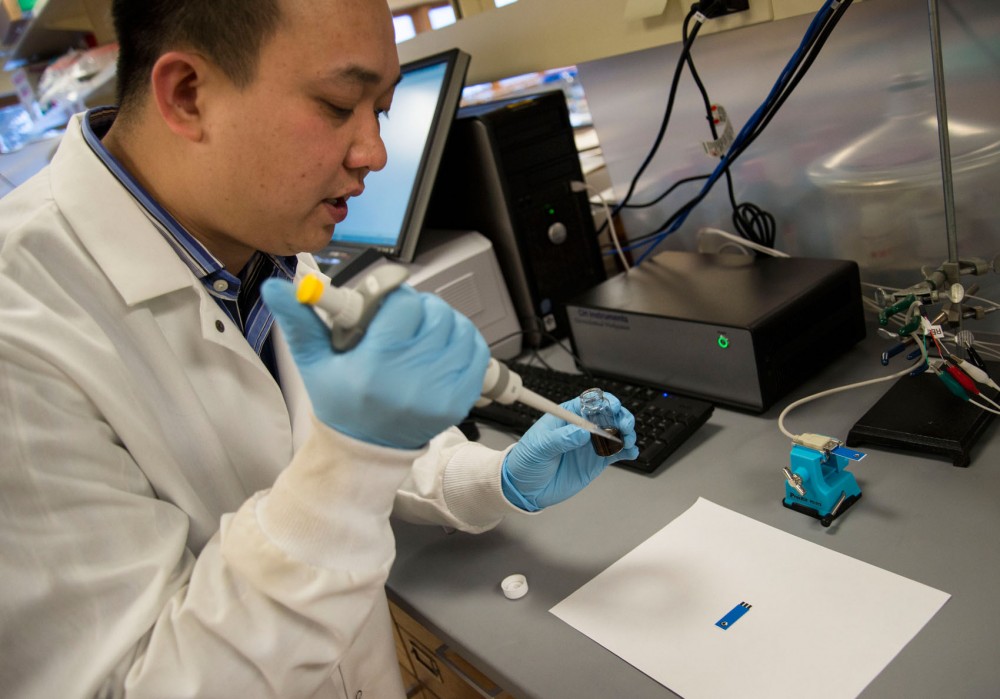

Researchers are trying to help farmers apply less nitrogen — a key chemical element of fertilizer — to their fields by creating a cheap, handheld device that immediately indicates the concentration of nitrogen already present in soil before applying fertilizer.

Minnesota’s Discovery, Research and InnoVation Economy initiative, known as MnDRIVE, has funded $36 million for research in key and emerging industries statewide. It financed the $40,000 research project shortly before the new year.

Each year, taxpayers spend almost $2 billion to remove nitrate — the water-soluble form of nitrogen — which is caused by agricultural runoff from drinking water, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Decreasing nitrate concentrations by 1 percent would save $120 million of that cost annually.

“We want farmers to optimize use of fertilizers, so we will save a lot of money, they will save money, and at the same time, we will help save the environment from nitrogen contamination,” said Abdennour Abbas, head researcher and bio-nanotechnology expert.

Nitrogen supports the growth of algae and aquatic plants in natural bodies of water. But when too much fertilizer is applied to a field, the soil can’t absorb it, causing it to leak into groundwater. Excess nitrogen in waterways can cause too much aquatic plant growth, which can starve fish and other organisms of oxygen.

The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency reported in 2013 that the state contributed the sixth-highest nitrogen pollution load to the low oxygen zone in the Gulf of Mexico. It also estimated that 73 percent of the pollution came from agricultural sources.

“I think it’s undeniable that agriculture does play a large role in [nitrogen pollution],” Luhman said. “It’s unfortunate, and it’s kind of a necessary evil.”

Most farmers want to know how much nitrogen is in their soil, he said, but it’s tough to test the land in small enough increments to apply the correct amount everywhere, especially when some farmers have thousands of acres of land.

The best Luhman can do now is send soil samples to a lab that analyzes concentration levels of nutrients like nitrogen. Each analysis costs about $30.

“With the handheld device, we’d be able to do it a lot more frequently,” Luhman said, “and we’d know right away, so the turnaround of results would be without the hassle of having to go through the laboratories.”

Agriculture education senior Sarah Lee said the cropland on her farm, though not organic, is also tested for nitrogen regularly. Her farm, in Poplar Grove, Ill., buys fertilizer from a local company that tests the land before applying fertilizer. The testing is also done in a lab, and the results only give an average of the field’s nitrate concentration.

“If growers can see those nitrate differences and then can change the fertilizer rates on the go, growers could soon have a tremendous tool for managing nitrogen inputs in very responsible ways,” said Bruce Montgomery, supervisor of the state’s Department of Agriculture fertilizer management unit.

The idea of an onsite nitrate soil test is not new. A few other companies have developed sensors, head researcher Abbas said, but none have been made as small, portable or sensitive as his team’s.

If things go well, he said, the University hopes to work with the state’s Department of Agriculture and Rowbot — a Minneapolis-based startup that aims to develop robotic solutions to problems in agriculture — to put the device on the market for farmers.

It would take at least a few years before farmers could purchase the product, Montgomery said.

Both Luhman and Lee said they’d be interested.

“As long as it is accurate and affordable, I’m sure it would find its way into many hands in agriculture,” Lee said. “The more information we have on our land, the better we are able to take care of it.”