One of only two living plaintiffs in the recently settled lawsuit regarding clinical trials based on discredited cancer researcher Anil Potti’s work spoke to the national cancer research publication The Cancer Letter about her treatment for breast cancer.

Joyce Shoffner—who is now 68 years old and lives in Raleigh, N.C.—was reportedly the first patient in a fraudulent trial based on Potti’s research that aimed to customize treatment based on an individual cancer patient’s characteristics. According to Friday’s article in The Cancer Letter, Shoffner became the trial’s first patient in July 2008 and previously was employed by the University.

By November 2010—when she became aware that the trial was terminated due to “problems with the data”—Shoffner said she felt deceived by those who had filled her with hope more than two years earlier.

“A researcher, doctor, had come up with a way of treating personal cancer—my own cancer, not general cancer, but mine, my tumor,” Shoffner told The Cancer Letter. “They were going to look at the DNA of my tumor, and from that Duke and Dr. Potti would be able to tell which chemo was correct for my type of cancer. They were saying that with this treatment, these tumors—they used the words—‘would just melt away.’”

One of the most vivid memories Shoffner had was doctors telling her that metal clips might need to be inserted near the tumors in her body to mark their location because of how effective the customized therapy could be.

“They implied that people had been having such wonderful results that they would have to put titanium clips around my tumor, because these tumors were melting away rapidly,” she said. “And by the time I finished my chemo, there may not be any tumor left, and they would have to go by those nine titanium clips that they inserted into my body to remove the residue.”

To become eligible for the clinical trial, Shoffner underwent two biopsies, the second of which provided tissue to be used in Potti’s genomic analysis to customize therapy. Although she said the second biopsy was very painful, going from under her arm up into her neck, Shoffner explained that she thought “it was going to be worth it” because of the way Duke had promoted the treatment.

“They advertised publicly that this science offered an 80 percent cure rate,” Shoffner said. “To have the type of cancer I had, I was just going to do that, there was nobody that was going to stop me, because this was what I was told and this was what I believed was going to happen.”

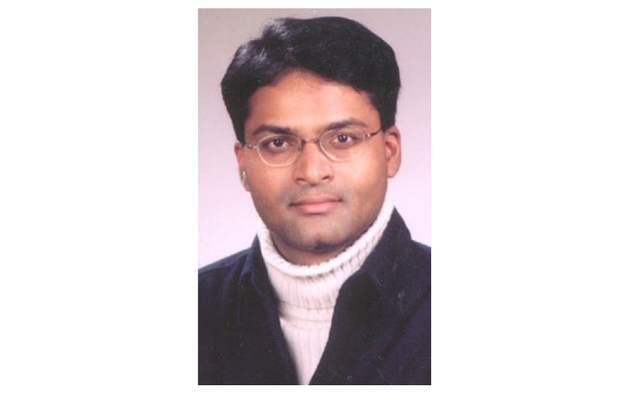

One such advertisement for Potti’s gene-based models can be viewed here:

“The goal is to be able to tell patients with cancer that I’m not just a cancer doctor, I’m here to treat your particular cancer,” Potti said in the advertisement. “The way to get to that goal is to do prospective clinical trials. So what I would say to patients is to inquire about prospective clinical trials that use genomic testing to try to determine whether they’re getting the right chemotherapy option or not.”

Before Shoffner signed up for the clinical trial, multiple members of the medical community had raised questions about the validity of Potti’s research, including biostatisticians Keith Baggerly and Kevin Coombes at MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston. Bradford Perez—at the time a third-year medical student who worked in Potti’s lab—had also come forward and reported concerns about the research to Duke administrators.

It was not until Paul Kelly Marcom, associate professor of medicine and Shoffner’s oncologist at Duke, told Shoffner that her trial was canceled in November 2010 that she learned there had already been multiple investigations into the trials. In January, The Cancer Letter reported that University professors and deans allegedly quieted Perez in 2008 when he raised concerns about Potti’s findings.

“All of it was based on people, but the people were kept in the dark,” Shoffner said. “Why did we not at least have honesty? Why was there not some integrity with this when it came to the human life? Why could decent human beings do this to other human beings?”

READ: Scientific misconduct expert says Potti settlements ‘do not resolve Duke’s responsibilities’

There are no more pending lawsuits regarding the clinical trials based on Potti’s research—which treated 117 patients—involving the University after the recent settlement. Administration has declined to comment since the settlement beyond noting that there are no further claims and once again declined to do so after the most recent article in The Cancer Letter.