University of Minnesota researchers published a scientific review last month on a type of cell that can lead to age-related diseases in hopes that their findings will lead to healthier and fuller lives.

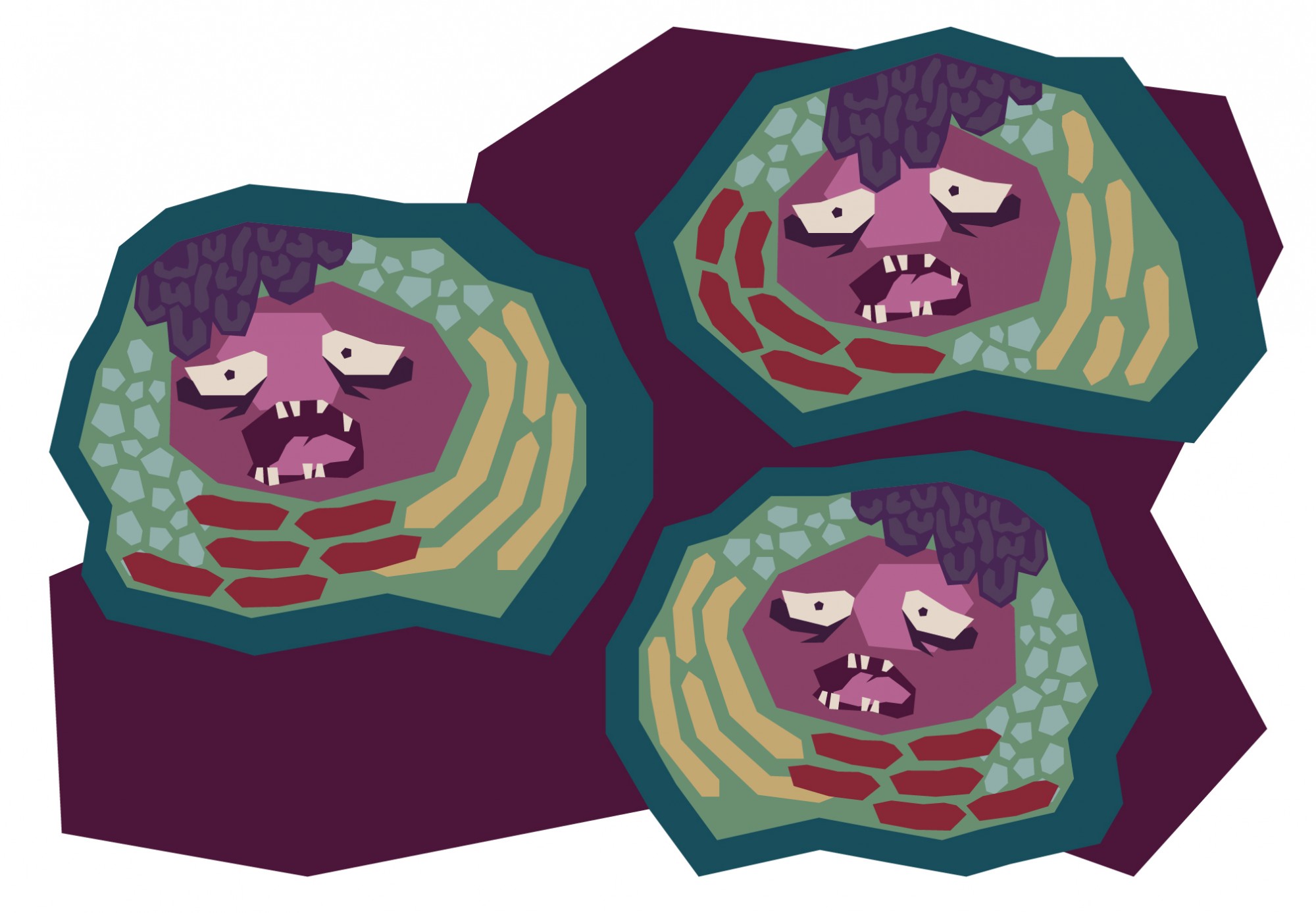

Senescent cells — also known as “zombie cells” because they are damaged and unable to die — are tied to a myriad of age-related diseases and conditions like osteoporosis, Alzheimer’s disease, heart disease and even general feelings of frailty. The scientific review, which was a collaboration with researchers worldwide, pointed out that while the field including senescent cells is expanding, some foundational knowledge surrounding these cells is still unclear.

“The intention [was] to gain consensus across the field, about how to define senescent cells, and then how to find them in an animal or in a person, because the definition is very loose at this point,” said Laura Niedernhofer, a contributing author to the scientific review as well as the director for the Institute on the Biology of Aging and Metabolism at the University.

Researchers said the advancement of this field, likely, will not prolong people’s lives. However, the elimination of these cells will allow individuals to lead healthier lives with less hospital care or age-related diseases.

Niedernhofer said centenarians, or people who live to be 100 years old, give proof that this is possible.

“And so how do we turn all of us into somebody who ages just as beautifully as they do?” Niedernhofer said, pointing not to how long centenarians live, but to their lower medical bills and fewer health complications as they age.

Senescent cells are not all harmful. In fact, many help to repair wounds and aid in growth while the human body is developing.

“In general, we think of them as being very bad … and that’s why we want to target them with drugs and clear them to slow the onset and progression of age-related diseases and aging itself. But there’s also what we call ‘sort of good senescent cells,’” Niedernhofer said.

Notably, the “good” senescent cells naturally remove themselves over time. Similar to the targeted senescent cells, the function and use of these cells are currently poorly defined.

Specifically, attempting to address age-related diseases holistically through the removal of senescent cells is relatively new in the medical field.

“We can use genetic tricks to target those cells and eliminate them … getting rid of those cells could potentially be an intervention for [age-related] conditions,” said Nathan LeBrasseur, who works with senescent cells at the Mayo Clinic as a consultant in the Department of Physiology and Biomedical Engineering.

Research on senescent cells in humans began earlier this year and is still being developed. The field is moving extremely quickly, said Paul Robbins, associate director for the University’s Institute on the Biology of Aging and Metabolism and co-author of the review.

“I do think that we’re progressing in the clinic faster than the basic sciences keeping up with it,” Robbins said. “As we do the clinical trials there’s going to be more and more questions we have to go back to the bench to address.”