Some faculty and staff at the University of Minnesota have raised concerns about the amount of money designated for yearly pay raises, which has remained stagnant over the past decade.

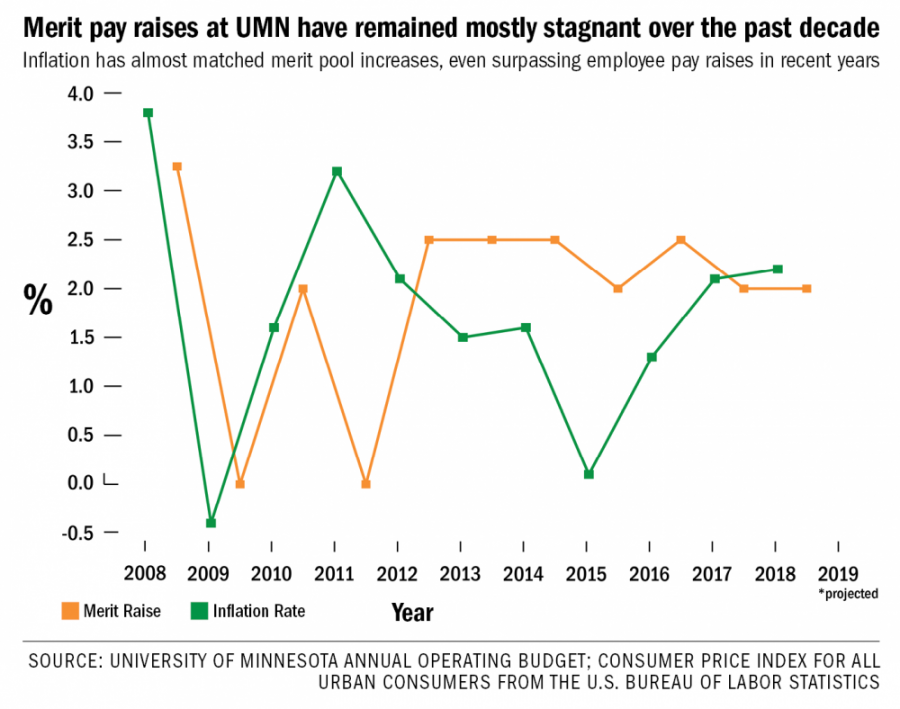

The University has provided fairly consistent raises since the fiscal year of 2009 — averaging around 2 percent general wage increases per year — which some faculty and staff say is too small to adequately reward employees. Inflation rates have practically matched raises during that time.

“When our budget increases are not significantly exceeding inflation, it’s very hard to make substantial merit increases,” said Joseph Konstan, chair of the Faculty Consultative Committee. “We haven’t had substantial increases with substantial leeway for recognizing large differences in merit for a number of years.”

The University has put forth a “modest” 2 percent general wage increase in the fiscal year 2019 annual operating budget. Inflation for the year is around 2 percent.

Konstan said faculty would like to see that amount increase.

“All workers would love to believe that we’re not just stagnant. We’re more qualified than we were last year. … We do our work with more experience and quality,” he said. “Therefore we should get [raises for] inflation plus some amount for merit.”

Brian Burnett, senior vice president of finance, said the University’s budget has tightened since the Great Recession in 2008, which has strained raises.

“What we’ve tried to do in the last few years is [to] bring salary increases that were affordable,” he said. “I get that faculty and staff would like a bigger salary pool, but this University has to be mindful of costs and lives within its means.”

Burnett said the University is looking at increasing merit raises in the coming years, though he did not specify an exact amount.

“We know inflation is inching up and that’s why we are looking at different numbers for upcoming merit pools,” he said. “We just have to make sure we have the resources to be able to provide those increases.”

The University puts forth a merit increase pool every year, which is set as a percentage of the total salaries of employees within colleges, campuses or support units designated for employee raises. The pay increases are meant to reward employees for merit and performance.

University units can divvy up money among employees, but typically cannot exceed the total amount provided for the year.

College departments typically determine how to split up money among faculty based on annual reviews. For example, a department could provide high-performing faculty members with a 3 percent raise, while granting others with a 1 percent raise, which would fall under 2 percent of all salaries in the department.

The chemistry department ranks faculty members based on teaching, research and service, said department head David Blank. He says high performers usually receive usually a raise slightly above 2 percent.

“We are fortunate to have a number of extremely high-performing faculty members,” he said. “The struggle for me typically is I can’t reward that extremely high performance with that restricted pool.”

Doug Hartmann, chair of the sociology department, said differences in raises are small among members in the department. With each raise typically around a few thousand dollars for each faculty member, Hartmann said only a few hundred dollars separate those who receive higher raises and those who receive lower raises.

“The pie is so small to begin with,” he said. “So it’s really kind of an uphill battle.”

The result is that many faculty members are underpaid compared to peer institutions, Hartmann said.

Average salaries for professors at the University are on the lower half of Big Ten schools, according to data from the American Association of University Professors.

Inflation rates have come close to matching faculty salaries over the past decade, according to the AAUP, meaning many faculty are essentially making the same amount they were in 2008. This reflects a larger economic trend: Average wages for U.S. workers have remained stagnant for the past 40 years, according to the Pew Research Center.

Small raises can result in the University losing faculty and staff to other schools, who may offer more competitive salaries. Other employees may switch to other jobs within the University to negotiate a higher starting salary.

“You’re always under threat of losing your top performers, but I think the relatively flat growth of salaries over the past decade has made that more of a problem,” Hartmann said.

Rebecca Ropers-Huilman, vice provost for faculty and academic affairs, said although many faculty members may feel content as part of the University community, low raises can hurt morale among faculty.

“When you see you colleagues doing amazing work and pouring their heart and soul into their work and you’re not able to recognize that in a financial way in a way you would like, it’s frustrating,” she said.

Officials say that lacking public funding in recent years has only exacerbated the issue. When accounting for inflation, state funding for the University has dropped nearly 20 percent since 2008.

Although nearly 70 percent of this fiscal year’s budget goes to employee compensation and benefits, there simply isn’t enough money to go around, Burnett said.

“When we’re trying to be mindful of student costs and the state isn’t giving us the full request we ask for, it just puts pressure on margins and you have to look at the salary pool,” he said.

Currently, raises for faculty and staff are not accomplishing what they are designed to do, said Ian Ringgenberg, head of the Professional and Administrative Senate.

“The merit pool is the only thing you have available to increase salaries, and it has to do the double duty of rewarding merit and also addressing cost of living,” he said. “I’m not sure that the merit pool for anyone is doing the thing a merit pool should do, which is reward merit.”