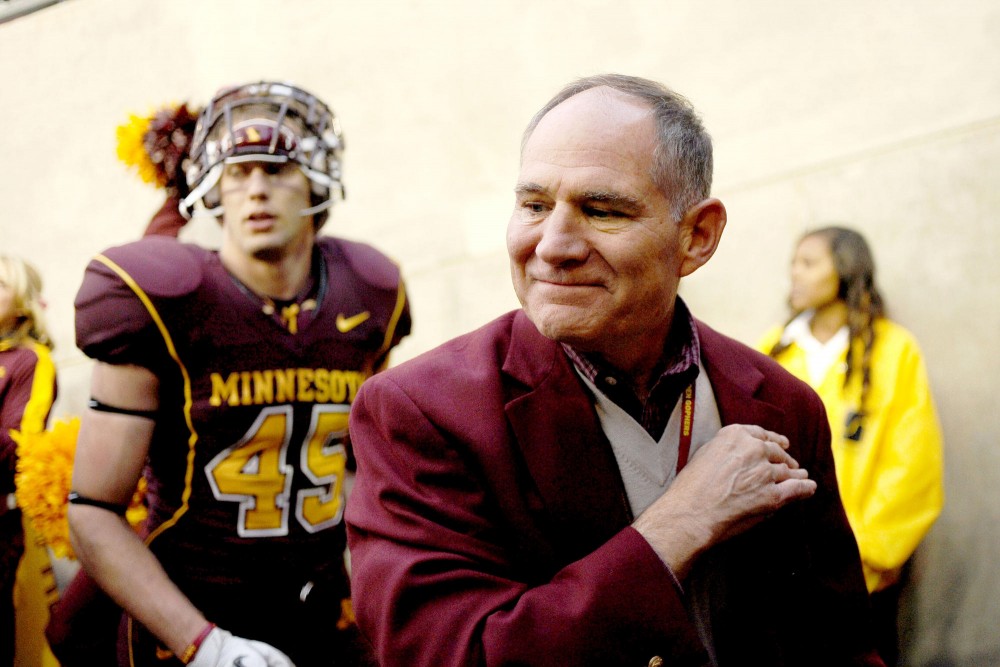

As athletics director Joel Maturi’s decade on the job comes to a close, many will remember him for his unrelenting dedication to non-revenue sports.

He knows the names of students on non-revenue sports, attends their games and cares about the scores. He’s been called the “champion of the little guys” — a title he wears proudly.

It’s also earned him the perception that he doesn’t pay enough attention to the big-money sports.

Maturi will step down as athletics director June 30.

As University President Eric Kaler and a search committee choose a new AD, uncertainties for the structure of the athletics department will arise for the first time in a decade.

One question looms above the rest: Will the University cut sports?

At a time when state funds are drying up and tuition is increasing, the University’s athletics department needed a $2.3 million subsidy from central administration to balance its budget last year. That’s the smallest since the men’s and women’s athletics departments merged in 2002.

A reduced athletics department is one way it could be self-sufficient. But the University would have to abandon its broad-based approach and some of its 23 varsity sports, only three of which make money.

Of self-sustaining athletics departments last year — 22 out of 228 schools made money, according to USA Today — the median number of varsity sports was 18.

There’s tension between two schools of thought: whether athletics departments should strive for the official mission of the NCAA — to make the educational experience of student-athletes “paramount” — or if the bottom line is all that matters.

Some say it’s possible to achieve both, but that’s getting more difficult. Increasingly, schools are choosing to cut back to save money.

Colleges dropped 227 teams between 2007 and 2009, according to the NCAA, mostly due to budget concerns.

“I think we’ll see a lot more programs cut [nationally],” said Stephen Ross, an associate professor of sports management at the University. “It’s just economics. It’s going to be hard to justify spending money on Nordic skiing, for example, on the few teams that are there.”

“The economics is too big. It’s way too big.”

Other schools cut

Examples of cutting sports reach from coast to coast, some within Minnesota’s borders.

The University of Maryland announced in November that it plans to cut eight of its 27 sports in an attempt to solve the athletics department’s multimillion dollar deficit.

The University of Delaware cut its $20,000 men’s cross country program as well as men’s track and field.

In Virginia, James Madison University cut seven men’s and three women’s sports to get in compliance with Title IX.

Bemidji State University cut its men’s track and field program to address a budget hole.

But not all sports that face cuts go under.

Mired with budget constraints, St. Cloud State considered cutting football, but students approved fees to save it and other sports.

Boosters raised $20 million to save several sports at the University of California-Berkeley.

The University of Minnesota almost dropped three sports in 2002, but a fundraiser rescued men’s and women’s golf and men’s gymnastics from the chopping block after then-President Mark Yudof proposed the cuts.

Since Maturi took over as athletics director that year, he’s defended a broad-based approach. With a new AD and president, changes to the athletics department are more likely than any time in the last decade.

But even Maturi has been a part of programs that cut sports. He previously served as AD at Miami University and the University of Denver — two schools that cut sports on his watch.

Following the press conference announcing his retirement, Maturi told the Minnesota Daily that he thinks Kaler will bring in an AD more familiar with business than himself. He lamented the increased emphasis on the business side of college athletics but said it’s the way of the future.

Defining success

Ross added that “while you hate to see astronomical salaries, paying the right guy, they can get somebody good.”

The University athletics department’s mission statement doesn’t claim that its purpose is to make money.

It’s designed “to serve as a window to the University, in an environment of integrity and equity, that enables student-athletes to achieve excellence in their academic and athletics pursuits.”

That mission statement hangs on the wall in Maturi’s corner office in the Bierman Field Athletic Building. He’s stuck by those principles, but a new AD may have different priorities.

Dave Mona, a former assistant to Maturi who’s on the search advisory committee to find his replacement, said the committee wants to “get a measure of what the AD candidates feel” about cutting sports.

“I do share a commitment to a broad range of sports,” Kaler said at the press conference announcing Maturi’s retirement.

“We just need to look at the financial viability of doing that, and I’m sure that will be an important element that the new athletic director will [address].”

The athletics department offers a variety of benefits to its roughly 750 student-athletes — like scholarships and academic tutors — as well as the larger University community.

The $79 million athletics budget made up about 2.7 percent of the University’s $2.9 billion budget in fiscal year 2011.

“What’s happened more recently is that in order to deliver on those [beneficial things], you have to run a really good business,” said Phil Esten, CEO and president of the University’s alumni association.

In the arms race of escalating coaching salaries and facilities costs in collegiate athletics, some equate success to the bottom line. Of the 228 Division I public schools, only 22 were profitable in 2009-10, up from 14 the previous year, according to the USA Today report.

The University’s program wasn’t ever self-sufficient under Maturi. But it has gotten closer and closer, even with ballooning budgets.

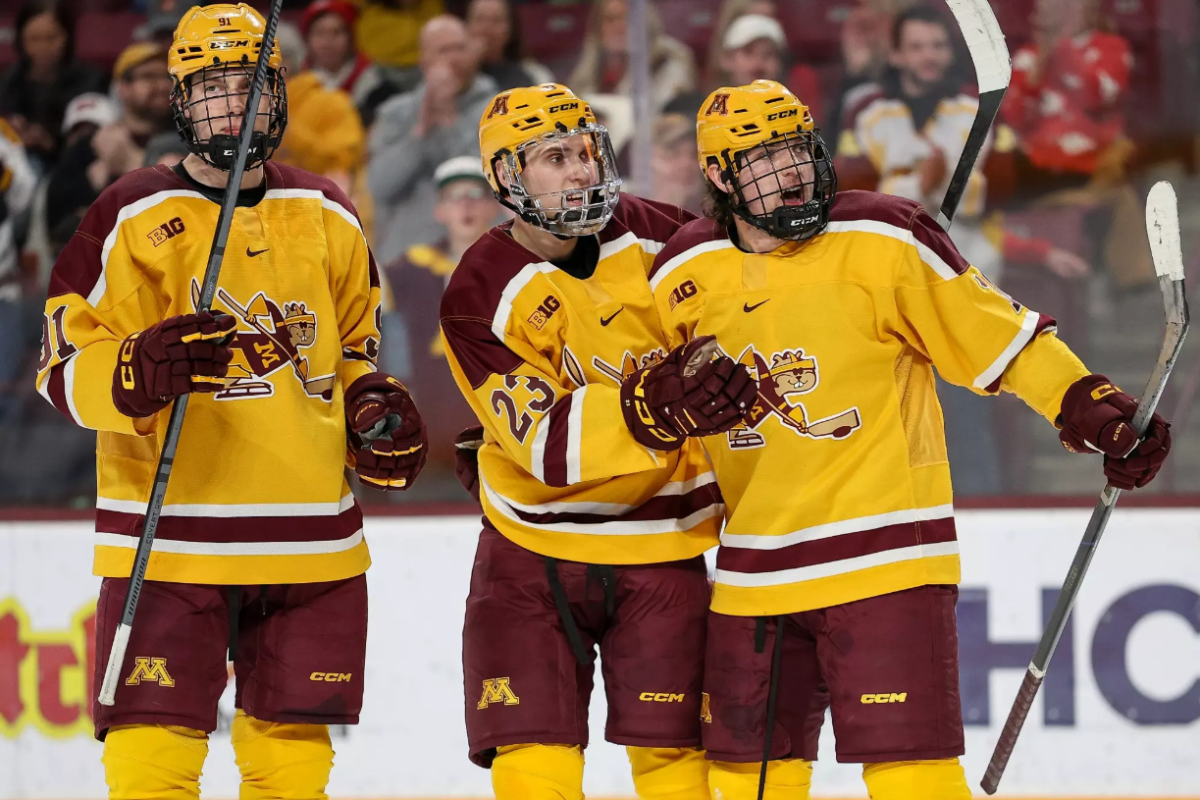

Only three of the University’s 25 varsity sports make money: football, men’s basketball and men’s hockey. If the decision to keep or cut sports was exclusively about money, the University would cut the other 22.

Cutting the women’s basketball team, for example, would save more than $2 million — almost enough to balance the 2011 budget without a central administration subsidy, according to the latest Equity in Athletics Disclosure Act report.

But experts say there’s more than monetary return from an investment in athletics.

Value

An athletics program’s value depends in part on the stakeholders it’s trying to serve. Big-time universities have a wide variety: student-athletes and the student body, faculty, staff, alumni, the state, donors, fans and even the Legislature.

Athletics can serve as a window to a university and extend its brand.

“A lot of sports here that we see as non-revenue are huge internationally, and that means a lot,” said Ross, the sports management professor. “And when you’re looking at an international university, trying to draw international students — the best and brightest from all over the world — that is important.”

Esten said he’s seen figures that show half of people who come into contact with the University do so for the first time through athletics.

“Seldom, if ever, can you find something for which 50,000 people identify with on any one day,” he said. “Truth be told, [athletics] is an investment to extend the University’s brand.”

Sports can also offer development opportunities for student-athletes.

Proponents of keeping a broad-based program say athletics fosters an academic environment, like other extracurricular activities.

Women’s cross country coach Gary Wilson defended non-revenue sports teams by comparing them to band and choir.

“This is supposed to be about education. This is not about making money,” Wilson said. “I think [cutting sports] is to the detriment of athletics and extracurricular activities as we know it.”

University student-athletes’ six-year graduation rates are consistently higher than the overall University average. Gophers student-athletes are on par with or outperform the national six-year graduation rate for their respective sport in every instance except men’s golf.

Maturi stressed education, community involvement and graduation for athletes at all talent levels.

“That’s a hard view to articulate to people, especially when they come with these preconceived notions of athletes being these one-dimensional zombies,” said Mike Torchia, a former cross-country standout, who is now enrolled in the University’s Medical School.

What does ‘cutting’ mean?

The conversation of cutting varsity sports is uncomfortable.

The most common option is to transition from varsity to club sports.

Club athletes get many of the same benefits as varsity athletes but without the funding. Travel budgets would be drastically reduced, and athletic scholarships would disappear.

Some have suggested a tiered model, where some sports receive full funding, others get partial, and the rest are deemed club sports.

Some boosters implore the University to reduce its number of non-revenue sports to increase funding for the football team.

Of the schools in the Associated Press top-25 in football at the end of the 2011 season, the median number of teams carried is 17 — fewer than Minnesota.

Generally, successful football programs are in narrower athletics departments.

But there are examples of successful football teams from broad-based departments — Stanford has 36 sports; Ohio State, 37. And still, many boosters argue adamantly in favor of keeping the non-revenue sports, too, Esten said.

Given the small budgets of non-revenue teams, Kaler, Maturi and sports economists said in interviews that cutting one or two would not save a meaningful amount of money.

“We aren’t losing, in my opinion, in football because we have 25 sports,” Maturi said.

If the University cuts sports, it “loses some standing as a major institution,” former men’s AD Mark Dienhart said.

Kaler said in his State of the University address that his goal is for the University to “be in the conversation about the great American public universities — such as Berkeley and Michigan, Virginia and UCLA.”

Esten said elite universities, including the kind Kaler mentioned, have broad-based athletics departments on top of their ranking as prestigious research and undergraduate programs.

“Excellence also means aligning our strategies with economic realities,” Kaler said in his address. “It is important to note that everyone has a role in identifying and implementing new ways to work smarter, reduce costs, enhance services and generate revenues.”

Although he wasn’t talking directly about athletics, his focus on efficiency may have implications for the department.

The athletics financial situation isn’t worse now than it was 10 years ago — it’s gotten much better. But the changing of the guard presents the possibility of a new direction.

Some have assailed college sports for over-commercialization and cheating scandals. The arms race is a more recent development.

Maturi considers the athletics department self-sufficient because it doesn’t collect parking revenue — which could help cover the deficit — and doesn’t waive out-of-state tuition for out-of-state student-athletes, like some schools do.

“I think Dr. Kaler is a change-artist kind of person. And I think he’s not averse to bringing change,” Maturi said of Kaler’s academic proposals, like a year-round calendar. He said the situation is similar in athletics.

“You can’t … do things the same way all the time and expect different results. Maybe there needs to be some changes, and I’m on the same page as he is with that.”

The University’s athletics department budget is the 20th-largest nationally, according to a report from the Memphis Business Journal. But Maturi and sports economists warn that “apples to apples” comparisons can’t be made between athletics departments because everyone keeps score differently.

The new AD may have to make choices: Do the benefits of a top-tier cross country team, for example, outweigh the nearly $2 million the men’s and women’s track and field and cross country teams lost last year?

Gopher men’s basketball made nearly $9.6 million in fiscal year 2011. The roster has only 15 members, so it serves a small number of student-athletes, but its reach stretches beyond that. It fills — or mostly fills — Williams Arena for home games and provides exposure for the University during its televised games.

Men’s swimming and diving lost $740,000 and has a roster of 43. In terms of student-athletes benefited, the swimming and diving team is superior to men’s basketball. But swim meets don’t draw a meaningful amount of spectators and therefore do comparatively little to extend the school’s brand.

The new AD will have to decide how much the athletics department values non-revenue sports.

“It’s a time to make decisions thoughtfully and delicately,” Dienhart said, “rather than taking a meat cleaver to them.”

ATHLETICS DEPARTMENT STRUCTURE OPTIONS

Land-grant U

This model offers sports based on interest and high school participation levels in the state.

Former adviser to Athletics Director Joel Maturi and noted booster Dave Mona said he’s talked with Kaler about engaging the Minnesota State High School League to find participation trends in the state.

He and others question why Minnesota doesn’t have, for example, men’s or women’s lacrosse or men’s soccer as a varsity sport, when they’re popular in state high schools.

There are thousands of kids in Minnesota that compete in sports that don’t turn a profit for the University. The Gophers competing and doing well in those sports is significant to them because there aren’t professional teams in the area.

“I’m not sure if we’re better served if we have a roster dominated by Eastern Europeans who is losing to a Michigan team dominated by Western Europeans,” Mona said.

Maturi lamented that he didn’t have the chance to add men’s soccer and women’s lacrosse before he retired as AD. But he added that allowing out-of-state and international students compete is important to the diversity of the department.

Bottom-line model

This model is strictly about improving marginal returns.

Because the NCAA requires football-playing member institutions to have 16 sports, the University would eliminate or reduce seven varsity sports to club level. Cuts would be based on which loses the most money: women’s basketball, hockey and rowing, and indoor and outdoor men’s track and field (counted separately by the NCAA), cross country and baseball.

This arrangement would throw gender representation slightly out of line because 99 male student-athletes would be eliminated and 113 female and so would need minor tweaks.

Since the model is concerned with efficiency, one tweak could be reducing the size of a men’s roster — say football — by 15 or 20 student-athletes to return the athletic department to University-wide male-female ratio.

Just make ’em pro

NCAA administrators cling to the idea of amateurism in collegiate athletics.

But Maturi said a professional or semi-professional model is closer than most people realize.

Women’s cross country coach Gary Wilson said college athletics shouldn’t be so concerned with making money, but rather teaching values to student-athletes.

“If your model is to make money, then you’ve got a professional sport. And if you have a professional sport let’s treat it like a professional sport,” Wilson said.

In this model, the money-making football, men’s basketball and men’s hockey teams would break off from the athletics department and operate like professional teams with all the caveats of professional sports. Athletes could be signed to contracts, paid, traded or cut.

The University’s central administration would fund the rest of the nonrevenue sports as it would other educational opportunities.

The University would lose nearly $28 million in fiscal 2011 net revenue from the money-making sports’ departure.

Generally it’s the same amount of scholarships, but they’re just given a different title (academic) and paid for by a different entity (central administration).

Former cross country standout Mike Torchia said the semi-pro model is not good for student-athletes.

“People forget the purpose — you’re missing out on this massive experience of college that goes way beyond sports,” said Torchia, who is now enrolled in Minnesota’s medical school.

Regional model

George Dohrmann suggested in an article published in Sports Illustrated a “market corrector” model, similar to the bottom-line model. It trimmed the fat from football and axed as many net-loss men’s programs as possible.

Football rosters would be capped at 90 and the number of scholarships reduced from 85 to 63. It would save athletic departments millions, according to Dohrmann’s research.

Many men’s sports would become club, losing all funding from the institution and paying their own way for any travel or team expenses.

Some sports may survive as varsity thanks to donors, but ultimately, not every sport would be saved. But sports that are strong regionally would likely draw the most support, Dohrmann suggested.

Hockey would survive in northern states. Baseball and golf would live on in the warm-weather southern states. West coast schools would likely save nonrevenue sports such as water polo and eastern schools would subsidize lacrosse.

TITLE IX

The most famous part of the Education Amendments Act passed in 1972 is Title IX.

It was not originally designed to address the disparity in gender representation in collegiate athletics but applies to public colleges because they take government funding.

The U.S. Department of Education’s Office for Civil Rights developed a three-pronged test in the 1990s to ensure a unified definition of “compliance” with Title IX. Schools must satisfy one of the requirements.

The “substantial proportionality test” requires that female athletes receive participation opportunities and resources based on the proportion of women that comprise the greater student body. The gender representation of a school and its athletics department must be within 5 percent proportionally and female student-athletes must receive a proportionate amount of scholarships.

Or, an institution must demonstrate a history of expansion and improving women’s sports programs.

The third option is the athletics department must prove it’s fully meeting the needs and abilities of its female student-athletes.