A University of Minnesota partnership is transforming food shelves across the state, looking to fill them with healthier options.

University research has shown that food shelves do not always make healthy choices easy. Hoping for change, the SuperShelf initiative is working to change what food is offered, improve food shelf designs and ensure funding is spent on food that clients want. Those working on the project aim to change more by the end of next year.

“We’re transforming these food shelves so they can become places for clients to access healthy and appealing foods,” said Caitlin Caspi, a researcher and assistant professor in the Department of Family Medicine and Community Health.

The basic principles of operation for some food shelves can be improved, Caspi said.

“If a food shelf is certified as a SuperShelf, it means it’s gone through a process … of evaluation,” she said.

SuperShelf certification aims to set a higher standard for food shelves around Minnesota, Caspi said.

The idea for the initiative began in 2013 with a partnership between Lakeview HealthPartners and Valley Outreach Food Shelf, originally called Better Shelf for Better Health. It grew from a pilot study to become the extensive partnership it is now.

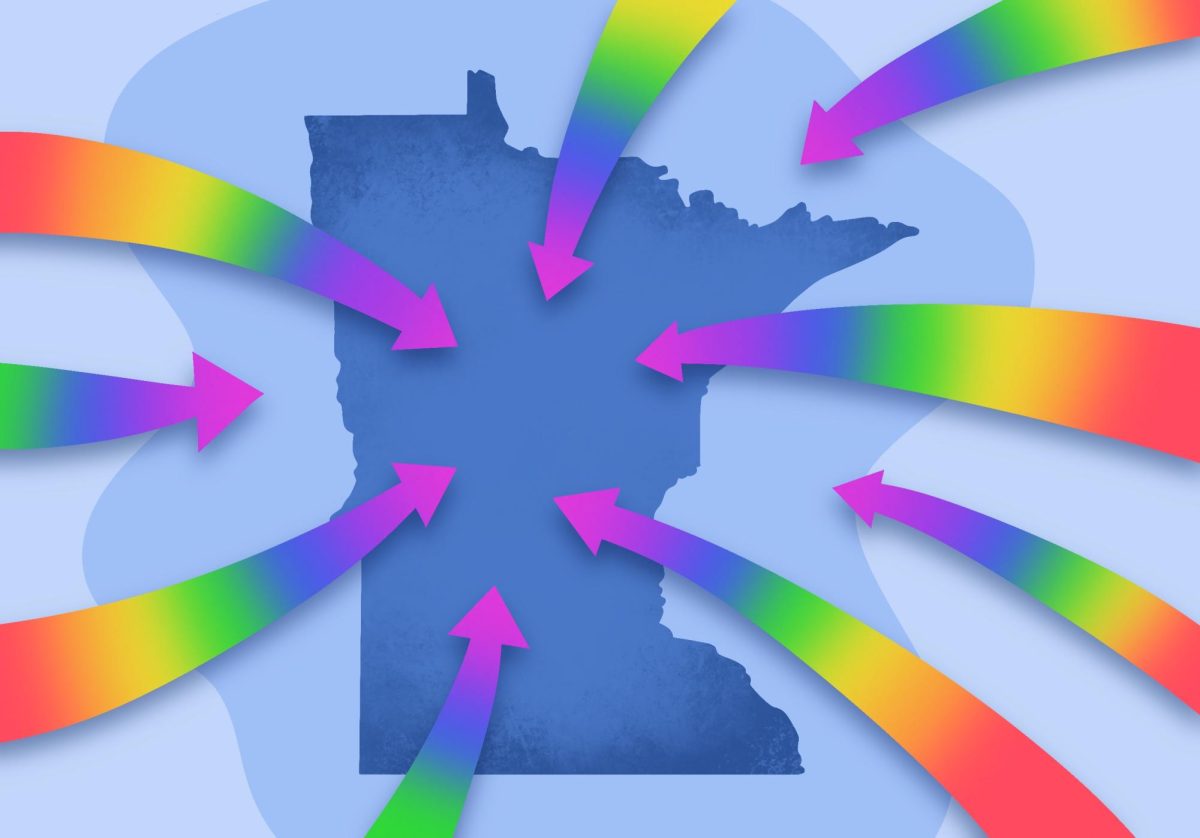

In 2017, the National Institutes of Health gave SuperShelf a grant to provide funding for 16 different transformations and evaluations. The initiative received more than 70 applications.

Due to interest, a dozen additional food shelves were transformed with support from the University of Minnesota Extension and HealthPartners, she said.

Deciding which food shelves would be a part of the first evaluation was difficult, Caspi said.

“It was more about this process of deciding which food shelves we were going to work with, making sure we achieved some equity in terms of outreach across the state,” she said.

Kelly Miller, director of the Department of Indian Work, one of the transformed food shelves in St. Paul, said SuperShelf really turned the shelf around.

“They were able to give us advice on how to order, what to order. It was really an eye opener to me,” she said about ordering food for families.

While they were ordering based on what clients wanted, most of the food was unhealthy, Miller said. Surveys showed that 90 percent of clients wanted healthier options.

“It made sense because the produce is expensive,” she said. Families can get canned or processed foods for a dollar or less, but they wanted fresher, healthier options, she said.

The new layout for the Department of Indian Work also includes culturally specific elements for its Native American clients, such as using Dakota and Ojibwe languages and designs around the food shelf, Miller said.

“Clients at a food shelf want the best food and health and outcomes for their families just like everyone else,” said Marna Canterbury, an initiative partner and the director of community health at HealthPartners.

Because of stigma around relying on food shelves, people are often hesitant to reach out, she said.

Some people assume that food shelf clients just need more nutritional education. Instead, they just want to be treated with dignity and respect, Canterbury said.

“People who are food insecure should have access to really appealing, healthy food. That’s what they want,” she said.